Escaping the summer sun, you dip down a shaded street in the heart of old Beijing. As you march through the arid heat and knee-jarring, solid streets of the Chinese capital, you tread in the footsteps of countless others. The journey has taken you to the northwest corner of the walled city of ancient times. Now in the city centre, this was once the far edge of the contained Yuan Dynasty city of the great Mongol Khans. You draw close to the later additions to the city; Qing Dynasty Lama Temple and the Ming Dynasty Temple of the Earth. It is a much older temple that pulls you along your path. Dating from the time of the Mongol rulers of China, the Temple of Confucius has seen all three of the great dynasties rise and fall. It is here, where scholars paid respects to the great teacher himself, that you find yourself standing.

The Beijing Temple of Confucius (北京孔廟 Běijīng Kǒngmiào), is a living history book of the dynasties who ruled China from the great city. Founded in 1302 during the reign of Temür Khan (元成宗 Yuán Chéngzōng), second emperor of the Yuan Dynasty (1271 – 1368 CE) and grandson of the founder, Kublai Khan (元世祖 Yuán Shìzǔ). The temple was built at the beginning of the decline of the short-lived dynasty that arose from the fallout of the great Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan and saw eleven emperors in less than 100 years. The huge temple space is the second largest temple of Confucius, the largest being in Qufu, the hometown of the sage. Used until the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912 CE), it was expanded during the Qing era and also the preceding Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644 CE). It is located near the School for the Sons of the State (國子監 Guózǐjiān) and the two complexes have a deeply intertwined history. The Guózǐjiān was the Imperial Academy and highest institution of learning. It is where the students (監生 jiànshēng) of high standing families would study the Confucian classics. The academy was built just four years after the temple in 1306 and was made defunct in 1905 by what came to be known as Peking University. Students went on to take the much feared three-yearly, Imperial Examination (科舉 Kējǔ), all hoping to pass with high marks and attain the status of “advanced scholar” (進士 jìnshì) and be given a high position in the state bureaucracy.

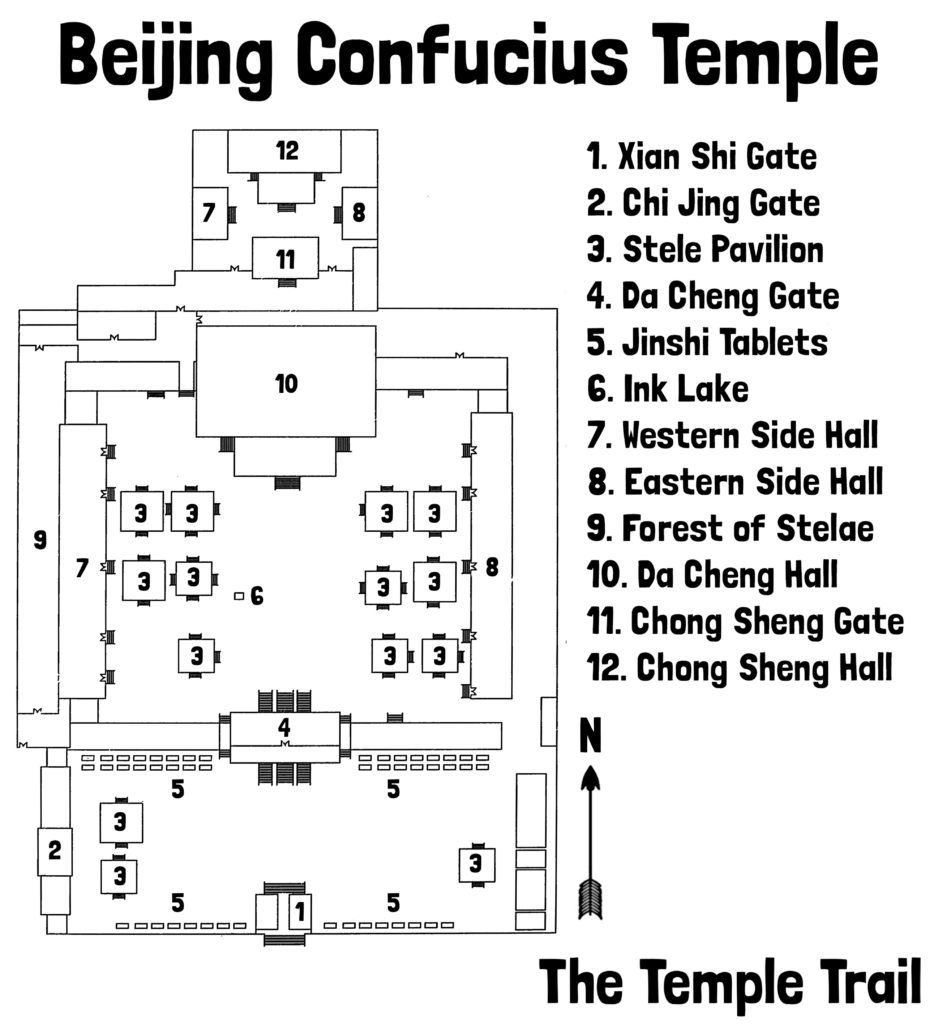

Arriving at the first entrance, you see that the street cuts through what was once temple grounds. Behind you, on the other side of the street, is the screen wall (照壁 zhàobì). This tripartite wall is deep red in colour and has glazed tiles decorating it. It was a supernatural defence against evil spirits, so that they could not enter the temple. Now separated from the temple by Chengxian Street, its purpose is more decorative these days. The first gate of the complex stands before you and you look over its decorative, but dusty roof brackets (斗拱 dǒugǒng). The Gate of the First Teacher (先師門 Xiān Shī Mén) has certainly felt the touch of Beijing’s famed air pollution and could do with a good cleaning. The beautiful green and blue paintwork shines through, however, and the gate maintains its grandeur. On either side of the gate is a pair of Qing era stones that bear the legend ‘official persons dismount’ in six different languages, thereby showing that the road has been here for quite some time.

Entering through the gate, you come into the first courtyard on the south-north axis of the temple. Standing in the middle of the tree-lined space, you note three large stele pavilions that each contain tablets inscribed with historical documents. To either side of the gate you have walked through and also beside the next gate are 198 stone tablets. These tablets are remarkable as they list the 51,624 people who achieved the rank of jìnshì. It is a list that encompasses 700 years of scholarly history. As you walk through the courtyard, you feel the pride and accomplishment of those men. You are an intruder on their territory. On the left of the court is the small side gate Maintain Respect Gate (持敬門 Chí Jìng Mén) and to your right are some small buildings with ceremonial functions such as the slaughter pavilion (宰牲亭 zǎi shēng tíng) and kitchen. These were where the attendants prepared offerings for worship. A modern statue of Confucius (孔子 Kǒng Zǐ) stands ahead of you at the end of the first courtyard.

Kǒng Fūzǐ (孔夫子), latinised as Confucius, has been honoured as the ‘Great Sage’ (Zhì Shèng 至聖) and ‘First Teacher’(Xiān Shī 先師) since ancient times. Born in the State of Lu in 551 BC, he was a member of the minor aristocratic class (士 Shì). The Shì were mostly military men and scholars, but Kǒng Qiū (孔丘) was raised in poverty by his widowed mother. He held various menial positions, but eventually rose to ministerial ranks. He is remembered for his teachings, which he developed throughout his long and mercurial life. He self-exiled himself from his home state and travelled throughout central and northeast China expounding his teachings on politics and governing systems, with no success. Although he did attract followers, none of the states took on his moral methods. He died in his home state in 479 BCE aged 71 or 72. After his death, his disciples successfully promoted his teachings throughout the Hundred Schools of Thought era (6th century – 221 BCE) using books such as the Analects and the Five Classics. During the Qin Dynasty (221 – 206 BCE), Confucianism was suppressed in favour of the rival system of Legalism. During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) it rose again, but had developed cosmological and metaphysical facets. It once more had a revival during the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE) when it incorporated elements of Buddhism and Taoism. This Neo-Confucianism is what became popular during the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 CE) and continued throughout subsequent dynasties with varying degrees of favour. Confucianism promotes a core set of ethical values that propound meritocracy, the mandate of heaven (天命 tiān mìng), superior person behaviour (君子 jūnzǐ) and the Five Constants (五常 Wǔcháng) – humaneness (仁 rén), righteousness (義 yì), proper rite (禮 lǐ), knowledge (智 zhì) and integrity (信 xìn), as well as “The Four” (四字 Sìzì) – loyalty (忠 zhōng), filial piety (孝 xiào), contingence (節 jié) and righteousness (義 yì). Along with this long list are also honesty, forgiveness, neatness, bravery, kind-heartedness, reverence, frugality and modestly.

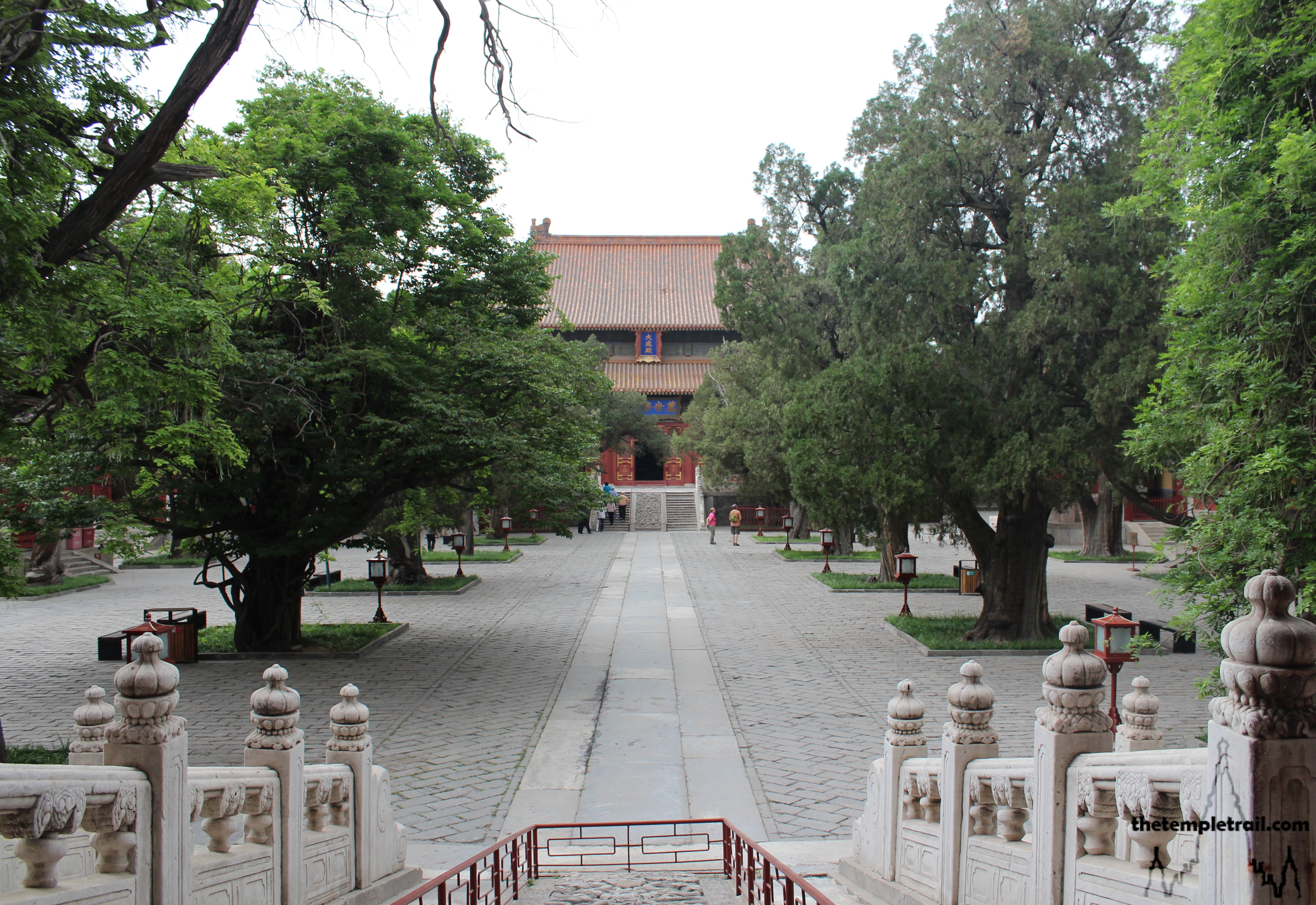

Looking into the face of the founder of the school of thought, you sense the profound depth of his tradition. In an ominous way, the sky begins to become hazy and the sun that was so bright before seems to lose its dazzle. After a moment or two, you pass the great scholar and walk up to the Gate of Great Accomplishment (大成門 Dà Chéng Mén). Built during the Yuan Dynasty and rebuilt during the Qing, the Da Cheng Gate is preceded by two ramps and a set of dragon steps. The central staircase is divided in the centre by an elaborate carving of hornless dragons. The steps lead up to a raised platform that the gate rests on. The roof is tiled with the glazed yellow tiles that are employed throughout the temple and the painted dǒugǒng are in far better condition than those at the first gate. The eye-catching hues pop out from under the eaves. Walking through the middle of five open bays, the roofed gate contains reproductions of Western Zhou Period stone drums from the Qing Dynasty and a set of 24 halberds (戟 jǐ). The ancient weapons are why the gate is alternatively named ‘halberd gate’.

Stepping out of the middle of the three doorways and into the second courtyard, you note that the stone flights from the front are mimicked on the way out. The court is enormous, and as you process down the middle, the space feels increasingly expansive. The cloister buildings that encircle the area are taken up with displays of Chinese cultural exhibits, but on the left is the stele forest. The 189 stelae a gift from the scholars of Jintan (a city in Jiangsu Province) during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (乾隆帝 Qiánlóng Dì), who ruled for most of the 18th century. They are carved with the Thirteen Classics (十三经 Shísān Jīng). The comprehensive canon of Confucianism is fairly small compared with other philosophies or religions; at the core are the Four Books and Five Classics (四書五经 Sìshū Wŭjīng). The Thirteen Classics were the basis for the Imperial Examination and all of them had to be memorised by successful scholars.

As you walk down the centre of the courtyard, you pass trees and pavilions housing stelae inscribed with important events, such as the suppression of the Hui Riots in 1759, or with eulogies such as Emperor Kangxi’s 1689 tablet praising the Four Sages (四配 Sì Pèi), the main disciples of Confucius. There are 77 disciples, but of these, the Four Sages and Twelve Philosophers (十二哲 Shí’èr Zhé) are the most respected. TheFour Sages are Confucius’ favourite Yán Huí (顏回), the Author of ‘Great Learning’ Zēng Zǐ (曾子), Confucius’ grandson and author of ‘Doctrine of the Mean’ Zǐsī (子思) and Mencius (孟子 Mèng Zǐ), second only to Confucius in the canon of Confucianism. As you continue towards the large hall ahead, you pass the Ink Lake (硯水湖 Yàn Shuǐ Hú). The lake is actually a well that contains particularly sweet water. It is said that writers who drink a cup of water from the well will be prolific and calligraphers who use the water to make their ink will have beautiful handwriting. It is for this latter reason that the Qing Emperor Qianlong conferred the title Ink Lake upon the well in the eighteenth century.

Before you begin to ascent the steps to the hall, you note an ancient cypress tree. This is the Chù Jiān Bǎi (Touch Evil Cypress). The tree was given the name after an incident from the Ming Dynasty. During the reign of the cruel and neglectful Jiajing Emperor (嘉靖 Jiājìng) between 1521 and 1567, the government was dominated by Yán Sōng (嚴嵩), the Grand Secretary. He was put in his position by the emperor, but was despised as being corrupt and amassed a wealth as great as that of the ruler himself. The corrupt official was passing the tree and a branch knocked off his official hat (粱冠 liáng guān). Thus, folklore gave rise to the idea that the tree had the power of discrimination between virtuous people and wicked ones. As you pass, you take the test and seem to have virtue. The steps that you begin to climb are very special and clearly mark the status of the temple and the hall you are about to enter. In the centre, the stone is carved with horned dragons vying for dragon pearls in the clouds. This is an image normally exclusively found in imperial palaces, as the horned dragon is the symbol of the emperor. The presence of the dragons elevates the temple to a very high status.

Rising higher than the dragons, you arrive at the doors of Hall of Great Accomplishment (大成殿 Dà Chéng Diàn). Da Cheng Hall is the main hall of the temple and before you enter the vast building, you look up at the façade. First built in 1302, it was rebuilt in 1411, after being destroyed by war, and had a green tiled roof installed in 1600. This was replaced with the yellow double tiered diàndǐng (殿頂) roof you see now, when the hall was expanded to a nine-bay and five-row sized hall in 1737. The paint is looking a little faded, but as you delve into the darkened depths of the hall, you find the interior grand and intriguing.

Occupying the centre of the hall is the shrine to Confucius himself. Under the intricately beamed roof, and adorned with rich golden drapes, a simple spirit tablet (神主牌 shén zhǔ pái) represents the great teacher. Before him, you note the ceremonial offerings and representations of a sacrificial ram and pig. Chinese people pay homage to him as you look on at the elaborately decorated, yet simple object of worship. The enormous space is home also a collection of musical instruments including a drum and part of a set of musical bells (編鐘 biānzhōng). The ceiling of the hall is painted in the customary blue and green, which contrasts strongly with the red curtains on the smaller shrines of the Shí’èr Zhé. The Twelve Philosophers usually have shrines on the left and right of the main hall of any Confucian temple, and this one is no exception. The 12 ancient Wise Ones occupy six positions on the east side – Mǐn Sǔn (閔損), Rǎn Yōng (冉雍), Duānmù Cì (端木賜), Zhòng Yóu (仲由), Bǔ Shāng (卜商) and Yǒu Ruò (有若), while the other six – Zǎi Yǔ (宰予), Rǎn Qiú (冉求), Rǎn Gēng (冉耕), Yán Yǎn (言偃), Zhuānsūn Shī (顓孫師) and Zhū Xī (朱熹) rest on the west side. All were direct disciples of Confucius, except for Zhū Xī. He was a Song Dynasty scholar who established the Neo-Confucian school. In front of the shén zhǔ pái for the twelve, are the same animal sacrifice substitutes. You see that locals have thrown low denomination bank notes in with the animal statues as their own offering to the twelve men.

Exiting the hall, the air has become incredibly hazy. In the short time you were inside, a pollution cloud has formed and the air has become toxic. Covering your mouth with your t-shirt, you venture round the back of the great hall to the Worship Hall, or Esteemed Sage Ancestral Hall (崇聖祠 Chóng Shèng Cí) that lies just beyond the Esteemed Sage Gate (崇聖門 Chóng Shèng Mén). The small memorial temple was constructed in 1531 as a place to make sacrifices to the five generations of ancestors of Confucius. Stepping through the páifāng-style gate, you enter into a small courtyard. The pollution forces you to swiftly take in the surroundings and make a sharp exit. As you dash back through the temple, the smog cloud seems to lift, and by the time you have cleared the front gate, the pollution has vanished. As you walk through the now gloriously sunlit streets, you think of the grand temple. It has stood through three successive dynasties, the Republic and the People’s Republic. It has enshrined the leaders of government, the scholars, for more than 700 years. Though it fell out of favour for a while, it is getting a new lease of life from the new leaders of China. Once more, Confucianism is rising and once more, the temple is becoming prominent.

Ħaġar Qim

Ħaġar Qim