The tram from central Hong Kong crawls along the tracks. You are rocked forwards and backwards as the driver accelerates and brakes the old wooden vehicle. The wind gently filters through the tram’s front windows, tempering the sauna-like interior. From the top deck, you are afforded views of the day-to-day hustle of the Sheung Wan and Kennedy Town districts. Coming to your stop, you alight and find your way to the uphill climb that you need to undertake. Not made for traffic, the wide street is made up of steps that seem to go on indefinitely. Passing concrete residential blocks on your ascent, you can hardly believe that this area holds a precious architectural gem in its heart. The grim 1970s buildings do nothing to convey their hidden secret. The fact that these practical, yet ugly edifices surround your destination is ironic. You reach nearly to the summit of the hill and make a left onto a slighter incline. As you get to the crest of the hillock, you see what you have come to seek. The small, yet perfectly formed Lo Pan Temple; shrine to the god of carpenters and builders.

Lo Pan (魯班 Lǔ Bān) was one of the legendary thinkers of ancient China. Born in the State of Lu (Shandong Province) in 507 BCE, the polymath was originally called Gōngshū Yīzhì (公輸依智). Under the backdrop of the tempestuous warring conditions of the Spring and Autumn Period (771 – 476 BCE), Lo Pan flexed his creative muscles. Lo Pan was a direct contemporary of the great Chinese philosopher Mòzǐ (墨子), the founder of the Mohist school of thought, a rival to Confucianism. He was a respected inventor, carpenter, philosopher, statesman and military strategist. Before his death in 440 BCE, he had amassed a large body of work. To his credit are a number of inventions of a military and civil nature including the cloud ladder (a siege ladder), a wooden carriage and coachman, a burial crane and a flying wooden bird. The latter is likely a forerunner of the kite and was able to stay in the air for three days. According to Mòzǐ, his services were engaged by the State of Chu and he created standardised weaponry for them in their war against the State of Yue. His contribution to their naval capabilities was grappling hooks for when the enemy retreated and rams for when they advanced. His inventions ensured Chu’s victory over Yue.

The life and works of the great man have been recorded in many volumes including the 3rd century BCE Book of Lineages (世本 Shì Běn), the 5th century CE Tales of the Marvellous (述異記 Shù Yì Jì), the 11th century Records of Origin on Things and Affairs (事物紀原 Shì Wù Jì Yuán), the 15th century Origin of Things (物原 Wù Yuán) and, the work attributed to the man himself, The Treatise of Lu Ban (魯班經 Lǔ Bān Jīng). The Treatise actually dates from sometime between the 13th and 15th century, making it almost 2000 years later than his lifetime. The worship of Lo Pan as a deity became popular during the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644 CE) and flourished through the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912 CE). Although only a few temples to the god were built, they were well spread through the empire, with temples from Beijing in the north, to Guangzhou in the south. Seen as the master of all craftsmen, Lo Pan was deified as the patron of builders and contractors and is still worshipped by construction workers from the trades of carpentry, masonry and plastering. As the mythos grew, stories of a flock of cranes spiralling above his home and a beautiful fragrance in the house during his birth became part of the folklore.

As you get closer to the small temple, you begin to make out its unique styling. Built during the rule of the British on 1884 by the Contractors’ Guild, the donations for its erection came from 1172 tradesmen in Hong Kong and Guandong. While typically quiet now, on the 13th day of the sixth lunar month, the celebrations for the Birthday of the Master make the temple a hive of activity. The temple was acquired in 1921 by the Kwong Yuet Tong, a management organisation made up of builders from Hong Kong, and they have maintained the temple since then. The temple embodies the ancient ideal of piety towards your teacher and your discipline. Being a temple of a celestial constructor, the building is fantastically made and has wonderful architectural features.

Standing now before the temple, the first thing you notice are the gable walls. These are the most prominent feature and are what have made the place so iconic. Production companies like to use the temple for shooting based on them and you can see it in movies such as Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story. The sharp pointed gable walls are in the style called the ‘Five Famous Mountains Paying Tribute to Heaven’ (五岳朝天式 Wǔyuè Cháotiān Shì) and are very distinctive. The black and white decoration frames the outline of the walls that in turn frame the two-hall temple and its platform. The style comes from Hunan in China, but here it is totally unique and the five interlinking wall sections point to the sky unlike any other in Hong Kong. The tall walls also enhance the façade that is almost two storeys in height.

Looking between the gable walls, you take in the roof with its dynamic ceramic figurines. Made of Shíwān porcelain (石灣窯 Shíwān yáo) from Foshan in Guangdong, the figures lean forward to allow those on the ground to see them clearly. In the centre of the roof of the rear hall, a pair of dragons vie for a blue pearl above a typical street scene filled with smaller human figures. Another similar Cantonese opera scene on the roof of the front hall is framed by a pair of phoenixes. Above the tableau two dragon fish make the temple particularly distinct. The pair have bulging eyes, making them stand out from other depictions of these fire-prevention beasts. The tails reach for the sky as the watch out over the temple, ensuring its safety from fire. On left and right corners of the roof are depictions of the sun god (太陽神 Tài Yáng Shén) and the moon goddess (太陰娘娘 Tài Yīn Niáng Niang). They hold a sun mirror and moon mirror respectively. One legend of the pair says that they were originally the attendants of the Jade Emperor of Heaven, but they quarrelled and were sent to earth as punishment. The Boy became the Duke of Zhou (周公 Zhōu Gōng), a historical honourable and noble man from the 11th century BCE, and the girl became Peach Blossom Maid (桃花女 Táo Huā Nǚ). Their quarrel continued and the Duke of Zhou, depicted as an evil fortune teller, tried to convince Peach Blossom Maid to choose an inauspicious day for her marriage, to cause her harm. She saw through his trick and managed to marry successfully. Eventually, the Great White Planet Venus (太白星 Tài Bái Xīng) mediated their argument and that is why the sun rises in the east and the new moon appears first in the west. The two deities here symbolise the balance of yin and yang and the transformation of bad luck to good.

Directly below each of these figures on the corner of the gable walls, you see matching sets of ceramics. An open book rests above a scene called ‘Martial Competition in the Imperial Palace’ which in turn sits above a scene called ‘Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove’. These pairs of scenes are crafted by masters of Shíwān pottery and the details, although small, pop out from the gable edges. Shifting your eyes to the mural above the door, you scan across the eleven individual painting that make the whole. There are a total of twenty-six murals at the Lo Pan Temple, but these are the most prominent. Either side of the central eleven are a picture of ladies and a picture of scholars visiting friends. The first image to your left is of Iron-crutch Li (李鐵拐 Lǐ Tiěguǎi), the most popular of the Eight Taoist Immortals (八仙 Bāxiān). Despite being grumpy and bad-tempered, he is a healer of the sick. Next to him is a small image of ‘Zhang Qian on a Log’. Zhāng Qiān (張騫) was an imperial envoy to the outside world for Emperor Wu of Han in the 2nd century BCE. He is a folk hero and is credited with opening up the Silk Road trade route with his travels. The large central picture draws your attention and you see that it is of six famous scholars. Among them you note the famed Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 CE) poet and gastronome Sū Shì (蘇軾), also known as Sū Dōngpō (蘇東坡), after whom the famed Hangzhou dongpo pork is named. Also depicted is the monk Fó Yìn (佛印). There is a famous story where Sū Dōngpō tried to play a joke on the monk, but it backfired showing the superior heart of Fó Yìn. Another contemporary figure is Huáng Tíngjiān (黃庭堅), the famous calligrapher and friend of Sū Dōngpō. This trio are common theme for Chinese artists. The message of the entire set of murals is one of education and striving for improvement.

Before you enter the temple and between the rhyming couplets (對聯 duìlián) that frame the door which praise Lo Pan’s contribution to architecture and wish his spirit can last forever, you look at the two plaster mouldings on either side of the door. Protected by a wire mesh, the one on the right shows the three heroes from the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE) legend of The Three Heroes of Wind and Dust (風塵三俠 Fēngchén Sān Xiá). The characters of the Lady with the Red Sleeves (紅拂女 Hóng Fú Nǚ) and her lover Lǐ Jìng (李靖) are shown with their ally the Dragon-Beard Man (虯髯客 Qiú Ránkè). The story relates how they helped overthrow the Sui Dynasty (581 – 618 CE) and establish the Tang Dynasty. On the opposite side is a scene of the ‘Four Hoaryheads of Shang Shan’ (商山四皓 Shāng Shān Sì Háo). These four elderly wise men went into secluded retreat to escape the politics of the Qin Dynasty (221 – 206 BCE) and refused to serve the first emperor of the subsequent Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 CE). When the Emperor Gaozu (漢高祖 Hàn Gāozǔ) wished to change his heir, the Four Hoaryheads were requested to help the heir-designate (劉盈 Liú Yíng) retain his position. His mother, Empress Lǚ Zhì (呂雉), convinced the wise men to come. Their mere presence with the kindly prince, caused him to succeeded his father and become Emperor Hui (漢惠 Hàn Hùi). The four men, whose legends escalated over time, came to be revered and worshipped in their own right and are symbolic of the virtue of principled conduct.

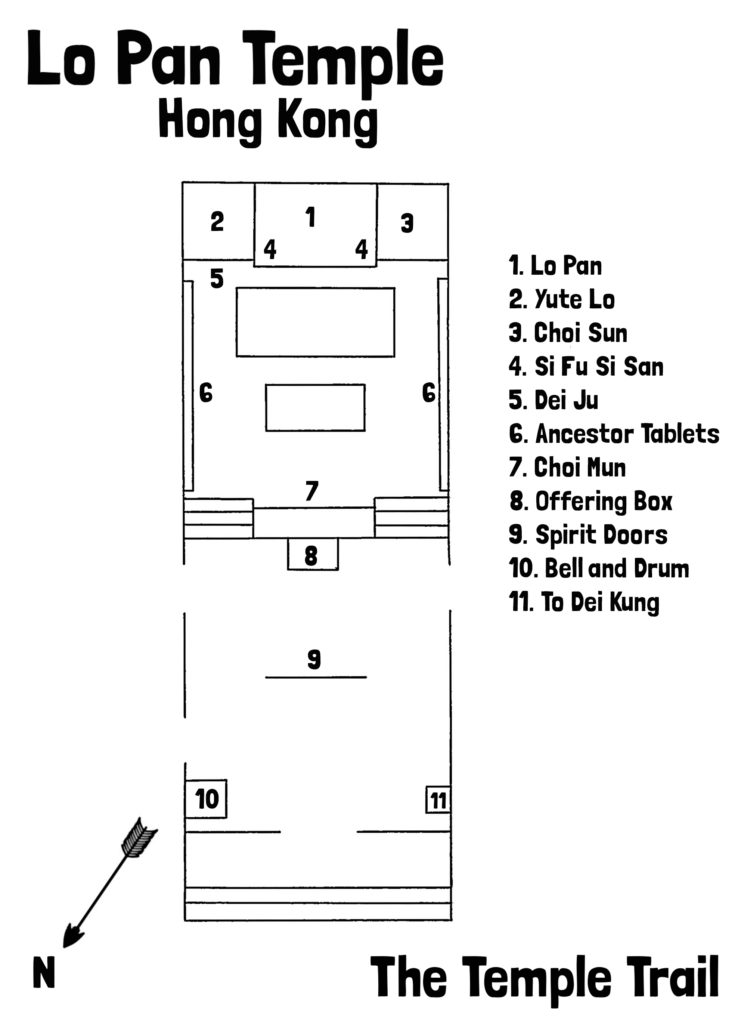

On the back and gable walls are more small plaster scenes including an image of ‘The Drunken Poet Li Bai’, showing the famed poet Lǐ Bái (李白) in one of his infamous states, and a tableau of ‘Zhong Gui Attracting Bats with a Fan’. Zhōng Kuí (鍾馗) is the King of Ghosts and the demon queller. Having committed suicide, the ugly scholar became a powerful ghost who was first seen in a dream by Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang Dynasty (唐玄宗 Táng Xuánzōng). His image is often placed on doors to act as a guardian spirit. Finally, you enter the doors of the temple, guarded by the two Mun San door gods (門神 Mén Shén), and find yourself shrouded in shadow. As your vision adjusts to the darker, but naturally lit temple, another, not so mystical guardian greets you. The old man who fills the role of the temple keeper welcomes you in a stoic manner and, returning his nod, you explore the interior. A shrine to the right of the entrance holds a statue of To Dei Kung (土地公 Tǔ Dì Gōng), the earth god. The ancient god, so popular with the local people, holds a piece of gold in his hand and keeps watch across the entrance hall.

Walking around the dong chung (擋中 dǎng zhōng), temple spirit doors that keep out evil forces, you stand in the roofed smoke tower. Often, temples in Hong Kong are open at this section, but here, being a carpenter’s temple, it is covered. The temple construction employs old techniques of joinery, so it does not use nails to hold the timbers together. Looking up to the top of the tall structure, you see the restored rafters and purlins that have been so well fitted in honour of the great master. Hanging from the edge of the smoke tower, is the choi mun (彩門 cǎi mén), or “colourful doorway”, a boat shaped carving with intricate woodwork. Here, you see that it is old and simply lacquered and gilded. The choi mun is a status symbol for the temple and acts as a symbolic festive gateway to the main temple hall. More significant are the plaster scenes and murals on the left and right of the tower. The elegant figures are dynamically arranged to illustrate stories from the Investiture of the Deities (封神演義 Fēngshén Yǎnyì), the famous 16th century Ming Dynasty novel. On the right a side door is guarded by a tablet of the Mun Gun (門官 Mén Guān) – door official, adding to the protection that surrounds the space you are in.

Climbing the few steps to the level of the rear hall, past an interesting collection box, you pass slabs bearing ancestors’ names engraved in the stone to commemorate those who have died and contributed to the temple. In the centre of the hall is the main offerings table with a painting of the god on it amid the candles and pomelos. Behind the great table are the three main altars. Taking the route to the left, you stand before the smallest shrine; that of Yute Lo (月老 Yuè Lǎo or 月下老人 Yuè Xià Lǎorén). The Old Man Under the Moon is the matchmaker god and he is usually visited by young people looking for their match, couples seeking a happy marriage of anxious parents hoping for a partner for the child. Beneath him is a tablet that represents Dei Ju (地主 Dì Zhǔ), the Land Deity, or Landlord Spirit. He is different from To Dei Kung and has the full title of Dragon God of Five Places and Five Directions, Wealth God of Front and Back. His tablet is often found in houses and he is responsible for the prosperity of the home and protection of it from demonic forces.

Moving to the centre, you look up into the face of Lo Pan. The wooden statue is eerily lit by bare red light bulbs and he stares out ahead as if concocting new ideas in his creative mind. Sitting in front of him on his left and right are his two Si Fu Si San (師父侍臣 Shī Fù Shì Chén) – Skilled Master Attendants. The two diminutive figures are his servants and before getting an audience with the god himself, you need to go through them first. The master craftsman looks out across his house, built by those of his trade. The building, despite its size does not lose any of its grandeur. Having paid your respects to the god, you move on to the right. Here is Choi Sun (財神 Cái Shén), the wealth god. According to the Fēngshén Yǎnyì, he was a minister of the Shang Dynasty (1556 – 1046 BCE) called Bǐ Gān (比干) who met a terrible fate. Other stories have him as a general of the Qin Dynasty (221 – 206 BCE) called Zhào Gōngmíng (赵公明). He was said ride a black tiger and throw explosive pearls at the enemy. He sometimes carries an iron tool with which he changes iron into gold.

As you turn and make your way to the doorway to the front of the temple, you look above the portal at the beautiful ink mural of a pair of dragons flying in the mist. The vigorous action of the artwork is the master craftsmen’s parting shot in a temple that is a series of intriguing details that have absorbed your attention. The temple is like a picture book of Chinese mythology and history. Leaving it, you feel as if you have been in a lesson with the master builders as your teachers. The home of the great Lo Pan is nothing less than an architectural and artisanal gem that will continue to educate visitors for generations to come.

The Stone Churches of Bohol

The Stone Churches of Bohol

(唐玄宗 Táng Xuánzōng) (門神 Mén Shén) Thank you for the Pictures and text, jim

Hi Jim

My pleasure – I hope you found my work useful.

Thanks

Tom