Wandering through the streets of the Muslim Quarter in the ancient capital of China, you are in an ecstatic haze. The exotic aromatic smell of biang biang mian noodles floods your senses. Dried fruits and bundles of spices colour the scene and illustrate the diverse nature of the Silk Road and the cross-cultural pollination that shaped the cities of old China. As hawkers call out and beckon you to try their products and buy their wares, you dart down a particularly tight alley. The walking space is narrower than the area reserved for goods and stalls. Pushing through zealous traders and ignoring their banter, you press on to the end of the passage to Hua Jue Lane. At the end, a large walled complex occupies a space that is invisible from the main streets of Xi’an. Like a secret garden, you need to be next to it to see it. A mixture of Chinese and Arabic styling, the Great Mosque of Xi’an (西安大清真寺 Xī’ān Dà Qīngzhēnsì) is a direct representation of the Silk Road itself.

The wall does not give much away of what awaits you inside and, not until you pay the fee and enter the gate, do you fully see the mysteries of the mosque. First built during the Tang Dynasty in the mid-8th century CE, the complex has been expanded and elaborated throughout its almost 1300 year history. The fact that it has stood through five dynasties and two republics is testament to its tenacious foothold in the Chinese cultural and religious landscape. The Great Mosque has a history that is almost as long as that of Islam. The early Arab traders brought Islam into China during the lifetime of the Prophet Mohammed in the early 7th century. During the Yuan Dynasty, the resettling of Islamic artisans through Kublai Khan’s 13th century westward expansion led to assimilation and intermarriages that formed the ethnic minority Hui people (Chinese Muslims) that you see all over the Muslim quarter of Xi’an. Islam in China was further reinforced by the evangelising of Sufis in the 17th and 18th centuries. This mixed history has contributed to the unique structures here at the 12,000 square metre Great Mosque.

The mosque is said to have been founded in its current incarnation by Zheng He (鄭和 Zhèng Hé), a famous eunuch, admiral, diplomat and explorer. The Renaissance man was a favourite of the Yongle Emperor (永樂帝 Yǒnglè Dì) and he explored extensively while in command of the famous Treasure Fleet of the Ming Dynasty in the early 15th century. The mosque was built here in the foreign quarter called the Jiao Fang neighbourhood outside of the city walls. It was a time of great acceptance towards Islam in China and the predecessor of the Yongle Emperor, the Hongwu Emperor ( 洪武帝 Hóngwǔ Dì) had ten Muslim generals in his military in the late 14th century. His mosque was remodelled during the Qing dynasty in the 18th century, when most of the current buildings date from. The Shaanxi Provincial Government have protected the site since 1956 and in 1988 it was recognised as an important cultural relic by the Chinese government.

The first indication that you are in a hybrid is the memorial archway (牌坊 páifāng). The large ornate structure would be more in place at a Taoist temple and the 17th century páifāng is a mirror of the one at the City God Temple that lies in front of the Muslim Quarter. The imposing structure sits in front of a spirit screen (照壁 zhàobì) that now forms part of the western wall of the complex. The screen is a common feature in Chinese Temples and serves to keep out evil spirits. In this courtyard, near the entrance, are two stunning pavilions, either side of the páifāng, with multi-tiered roofs and elaborate craftsmanship. You could be forgiven for thinking you were in a Taoist or Buddhist complex. The give-away that this is a mosque is the ornate Arabic writing either side of the second gateway of the complex that you come to as you leave the first courtyard. The gate building is very much in the style of a Buddhist temple from the period and is called the Five-room Hall (五間房 Wǔjiān Fáng).

In the next courtyard, you are confronted with three connected stone memorial gateways from the Ming Dynasty that bear the legend ‘Court of Heaven’. The second courtyard also yields some pretty, but worn cloister buildings with a variety of functions and some lovely stelae. They are housed in a brick casing and they are a Chinese addition. The carvings of dragons, flowers, vases and screens would be more at home in a traditional aristocratic Chinese house than they are here, yet the cultural crossovers are what makes the site what it is. One Stele features the calligraphy of Mǐ Fú (米芾) from the Song Dynasty, the other of Dǒng Qíchāng ( 董其昌) from the Ming Dynasty; both famous calligraphers in their own right.

Passing through the third gateway, you come to the third courtyard, home to some of the most important structures. You note the Imperial Hall that contains the Moon Tablet (Yuè Bēi 月碑). This valuable stele is carved with the methods of calculation for the Muslim calendar and was created by a famous Imam called Xiao Xining. The Lecture Hall on the northern side has a hand-written copy of the Koran from the Ming Dynasty and a map of Mecca from the Qing Dynasty, it is the oldest building in the complex. The Bath houses or Water Rooms are also in this courtyard and worshippers go there to wash before prayer. The Imam would once have lived in this section of the mosque and the library was originally located here. The tallest part of the compound demands your attention from the centre of the court. Walking over, you are drawn towards the Pavilion for Introspection (省心亭 Xǐng Xīn Tíng). This octagonal three-storeyed building acts as the minaret of the mosque as well as being the moon watching pavilion. Designed in the traditional Chinese style, it has three flared eaves and is roofed with the same blue tiles as the páifāng and the Great Hall. Walking into the tower, you look up at the bright ceiling and its lotus flower decorations and yet again you are tricked into the feeling that you are in a temple rather than a mosque. As nature imagery is normally taboo in Islamic architecture, you note that most of the animal and plant imagery is higher up on the buildings, rather than at eye level. Perhaps this is a concession to more Middle-Eastern standards.

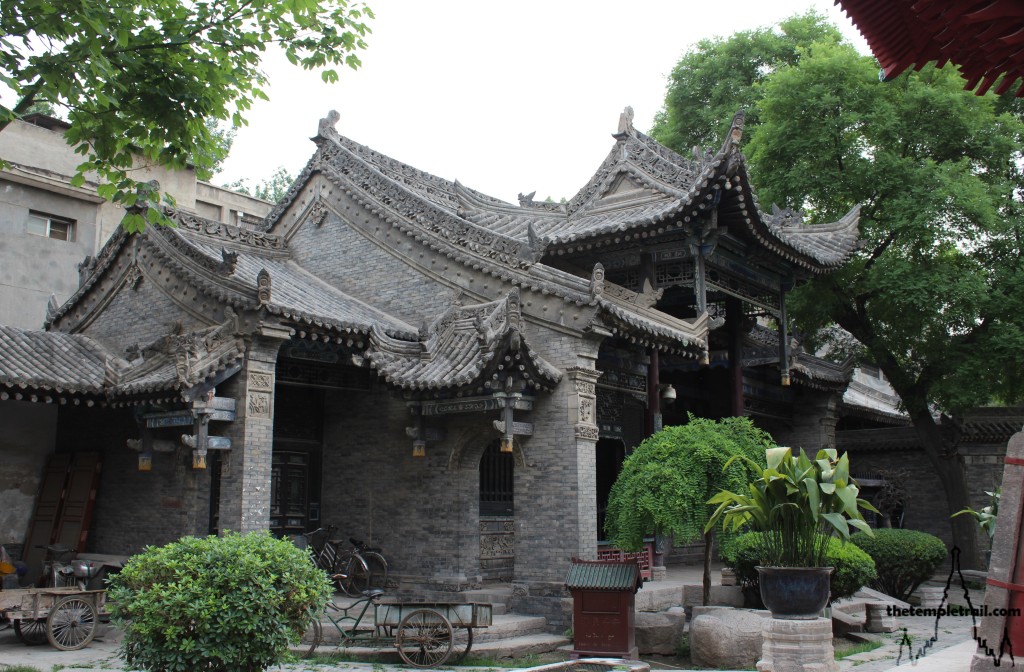

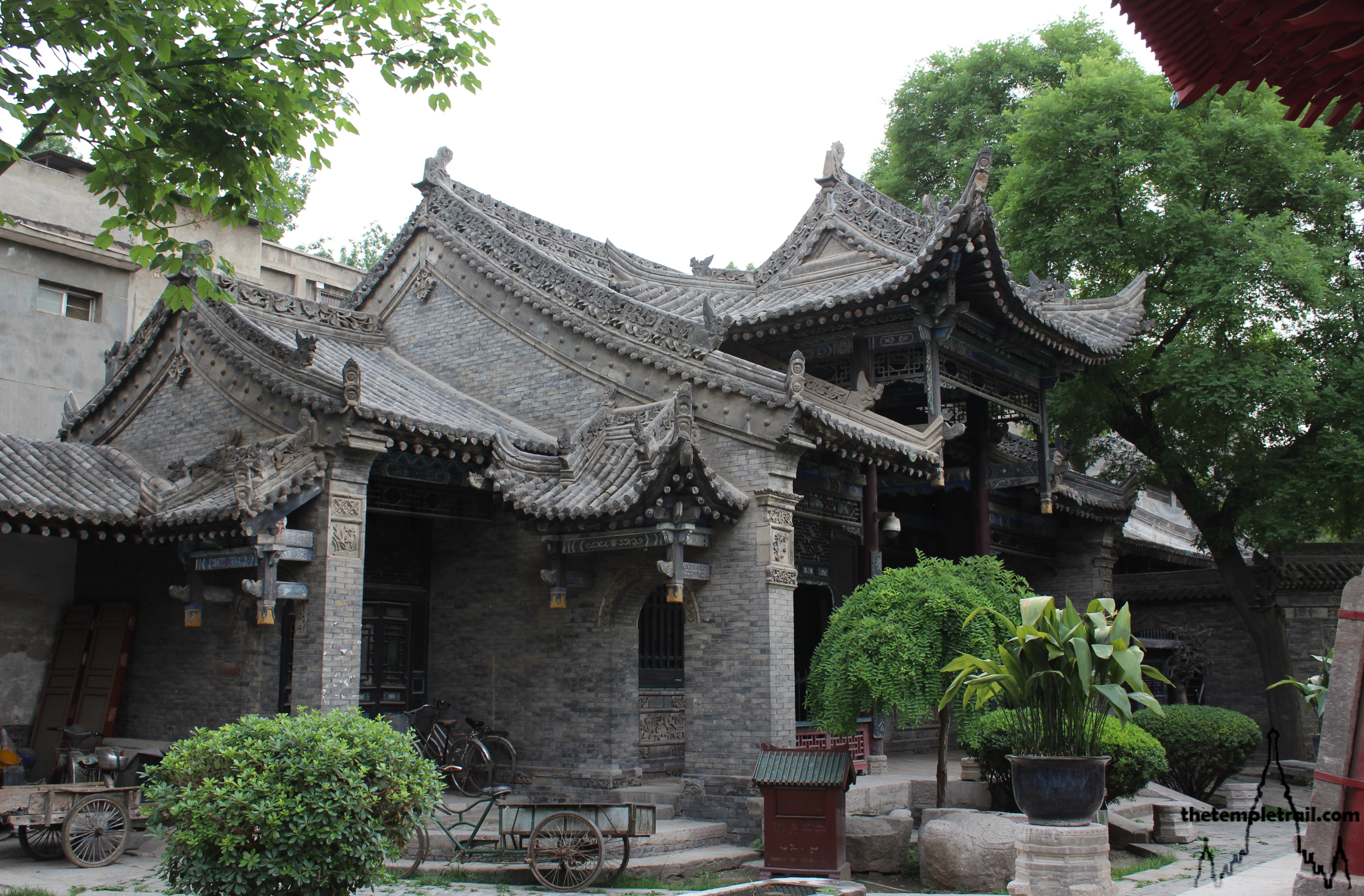

Exiting the minaret, you head to the marble gateway that leads to the fourth courtyard. This is the largest space in the complex and the buildings that line either side were originally intended for receiving officials and proclaiming imperial edicts. You head straight down the middle to the One True Pavilion (一真亭 Yīzhēn Tíng), better known as the Phoenix Pavilion (鳳凰亭 Fènghuáng Tíng). The pavilion is made of three structures joined by a connecting roof. The hexagonal central part is the largest and either side two triangular annexes make the shape of a phoenix, thereby giving the structure its name. Approaching it, your gaze fixes on a plaque with dragon carvings on the frame that hangs from the eave. It was written by a mandarin of the Ming court and simply states: “One True”, meaning One God. Beneath the intricate dragon-emblazoned roof is a table and chairs. You consider resting in this peaceful spot, but the finale of the mosque beckons you over.

Continuing on your direct east to west trajectory, you walk over a carved stone disk with two dragons on it and under a cloud gateway, up to the Moon Platform (月臺 Yuè Tái). The huge podium is made of granite and is the raised base on which the main focus of worship rests. Before you, the Great Worship Hall (大殿 Dà Diàn) and its five doorways occupies your entire view. The building is huge and is wooden with flanks of marble. It has a capacity of 1000 people and is the largest in China. Striding towards it, you are mesmerised by the panel above the central door. It is a beautiful piece of Arabic calligraphy and reads ‘In the name of God’.

The blue glazed roof tiles shimmer and walking under the eave, you marvel at the wooden frame that holds the great weight of them all. You cannot enter the hall, as it is reserved only for worshipping Muslims, but from the outside, you peer in to see the fabulous interior. The ceiling is lined with 600 classical scriptures on panels with colourful calligraphy in motifs of grass and flowers. The walls have 600 wooden carved panels of the entire Koran. Thirty are in Chinese, the other 570 are in Arabic. The thick columns are painted richly in red and divide the space into seven bays. The Structure is comprised of three sections, each with its own roof. The front porch, the prayer hall and the iwan are modelled on Han palace architecture, as are most early Hui mosques.

At the back of the Great Hall is the Rear Mihrab Hall. This is an iwan; a three walled rectangular hall that constitutes the most important part of most mosques. The mihrab (arched niche) at the back indicates the qibla (direction in which to pray) and points to the Kaaba in Mecca to the west. The mihrab is encircled by four bands of Koranic inscriptions and the Arabic writing has been heavily impacted upon by Chinese calligraphy. The space is fantastic and the air of mystery and sanctity is hard to ignore. Hypnotised by the darkened interior of the hall, you find it hard to drag yourself away. You yearn to cross the barrier and inspect it further, but your respect for the Hui faithful holds you back.

Through two circular gates, the fifth courtyard lies beyond the prayer hall. Two small artificial mounds for viewing the new moon occupy the space. You retrace your steps axially back to the first courtyard of the mosque. Walking through the site, you are journeying though a neglected part of Chinese history. Islam has been present in China for 1,400 years. The Hui believe that the Sahabah (companions of Mohammed) brought it to China when the prophet was still alive. The route you are treading has been trodden by generations of Muslims going right back to the very foundation of the faith itself. Feeling the weight of history upon you, reluctantly, you leave the peaceful oasis of the Great Mosque and head back into the hustle bustle of the Muslim Quarter.

hello I want to know who the publisher is because I am writing an annotated bibliography

Hi May

I am the publisher – Thomas Billinge

Thanks

Tom

Beautiful and fascinating article. Thank you for sharing 🙂

Thank you Brandon!