From the French concession, you traverse the city to an older section of Shanghai. Having torn yourself away from the easy living and Parisian ambiance of the cafes in the western part of the city you enter a grittier section of town. The old city does not have café au lait and baguettes, but it does have an earthiness and realness that brings you back down from your white tower in the European part of the city. The web of streets that you are navigating was once walled. All that suggests that this was the case is a crinkled map in your hand that has a circular ring-road around the area where the wall used to be. In the dark days of colonial superiority, the old city was where all Chinese people were confined. A walk on the nearby Bund was only allowed if accompanied by a Westerner. Today Shanghai has changed and exploded into a megalopolis of 23 million people or more. The population could not fit in the cramped lanes of the old city, yet some still call it home. You are heading to a point that was the focus for rituals and respectful worship for the local people for hundreds of years until the Cultural Revolution ended it. Thankfully, it has been resurrected as a phoenix from the ashes and once more the Temple of Culture (文廟 Wén Miào), the Shanghai Confucian Temple, is part of the structure of the old city.

Confucius (孔子 Kǒng Zǐ or 孔夫子 Kǒng Fūzǐ) was an educator, politician and philosopher from the Spring and Autumn Period. Born in the 6th century BCE, he preached personal and governmental morality and correctness. His disciples gathered his teachings and added to them to create Confucianism. Confucianism did not become a ratified system of conduct until the Han Dynasty came to power in the late 3rd century BCE. Confucianism teaches respect to elders, respect to authority and ancestor worship. It is a religious philosophy that those in power have generally preferred, as it reinforces the supplication of the masses.

This temple was officially recognised and expanded by the Mongol Yuan Dynasty in the late 13th century when Shanghai was a small trading town. However, a smaller hall of Confucius has stood in this spot since the Tang Dynasty. Over the centuries it was added to and renovated by the Ming and Qing Dynasties. TheSmall Swords Society (小刀會 Xiăo Dāo Huì) occupied the temple in the mid-19th century during the Christian-led Taiping Rebellion. The Small Swords were a paramilitary group that were associated with the Triads. They mostly hailed from the south of China and were eventually put down like the rest of the Taiping groups. Although the Small Swords were based in Yu Yuan Gardens, Wen Miao was an important command base. The Qing army razed the temple to the ground during the conflict, but the royal family rebuilt it in 1855. The temple remained relatively unharmed until the Red Guard broke into it during the Cultural Revolution. The damage done by the Maoist zealots remained and the temple was effectively abandoned until the government completed the most recent renovation in the temple’s history between 1995 and 1999.

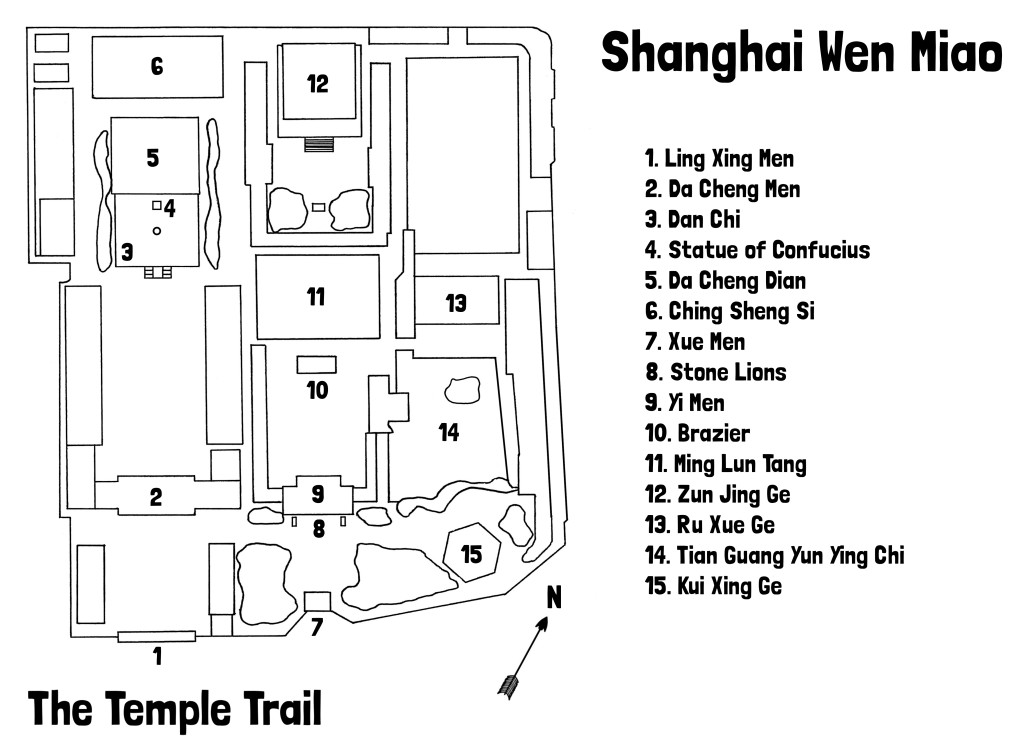

Before you lie three paths that run from the south to the north and, naturally, you take the first of them from the main entrance gate, called the Top Scholar Star Gate (櫺星門 Líng Xīng Mén). Passing through the next gateway, you stand in the central courtyard of the western temple axis. This path is the public worship route. The building ahead of you is magnificent in its simplicity. As you close in on it, the dragon on the stone that separates the staircase looks out at your approach. Above him on the raised platform (丹墀 dān chí) is a bronze statue of the great sage himself holding a sword nonchalantly under his arm. As he humbly watches you passing him by, you see the silent intelligence in his eyes. The hall embraces you in its darkness as you cross its threshold. The Hall of Great Accomplishment (大成殿 Dà Chéng Diàn) as you see it before you, was first built in 1294 during the Yuan Dynasty’s construction phase. During the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE), a smaller building called Wén Xuǎn Hall lay here. Wenxuan refers to the honorific title “Exalted King of Culture” (文宣王 Wén Xuǎn Wàng) bestowed on Confucius by Emperor Xuanzong (唐玄宗 Táng Xuánzōng). It wasn’t until Emperor Huizhong (宋徽宗 Sòng Huīzōng) of the Song Dynasty came to power in the early 12th century, that the hall was named Dà Chéng Diàn, to acknowledge the accumulated teachings of all past sages channelled through Confucius. When the Yuan Dynasty built the formal temple, they retained the name Dacheng Hall. The current incarnation is a Qing Dynasty rebuild from 1855.

Inside the dark hall, a golden statue glows in the centre. To either side of him is a drum and bell set. Normally Confucius is not represented in human form in a hall and is symbolically shown as a wooden tablet. Here, the sage is well formed in gold lacquered camphor wood. His pleasant demeanour shines forth and you can’t help but feel quite comfortable in his presence. In front of him sits the more usual votive wooden tablet. On the eastern and western walls are 52 bluestone slabs inscribed with the complete Analects of Confucius (論語 Lúnyǔ).

Withdrawing from the hall and into the bright sunshine, you skirt the side of it to the right, past prayers trembling in the wind, and out to another courtyard that lies on the second, central path. The cloister of the space is filled with beautiful natural rock formations and stelae on the walls. In the centre of the court is the Respected Classics Pavilion (尊經閣 Zūn Jīng Gé). Resting at the northern terminus of the scholarly path, this tall and aesthetically pleasing structure is the library of the temple. It serves as a place to keep the collections of philosophical writings of not only Confucius, but also of other noteworthy thinkers and Confucian scholars. The building was first constructed in 1484 during the reign of the Ming emperors. It rose to particular prominence in 1931, during the Republic of China era, when it became the first national library of Shanghai. Inside, the glass cabinets contain numerous volumes. This hall was built to pay homage to learning, academia and knowledge as teaching and study are sacred in Confucianism.

Passing through the central doorway of the cloister that surrounds the library, you first pass a huge natural stone that acts as a de facto screen. The next building on your scholarly route is the Hall of Moral Instruction (明倫堂 Míng Lùn Táng). The hall served as the lecture theatre for Confucian scholars. Here, the students would have taken instruction from their masters and contemplated the wisdom that was passed down for centuries. First built in 1351 during the Yuan Dynasty, the hall has some notoriety as the headquarters for the Small Swords Society leader Liu Lichuan (劉麗川 Liú Líchuān) in 1853. The hall was destroyed by the Qing forces when the rebellion was quashed but was rebuilt in the 1855 restoration. The stark contrast between the peaceful learning and the bloody violence that the hall has seen is testament to its turbulent history.

Yet another bright courtyard awaits you as you come out of Míng Lùn Táng and at the other end, past a brazier, is an entrance gateway. You take a left, rather than heading to the opposite side. Through a doorway in the cloister, is a small, but pretty Confucian garden based around a green-coloured pool called the Bright Sky and Cloud Reflection Pond (天光雲影池 Tiān Guāng Yún Yǐng Chí). Koi and other carp swim slowly around the murky water and you feel that in its depths lurks a monstrous fish. This is the third path of the temple; the nature route. At the northern end of the eastern path is the Confucian Study Hall (儒學署閣 Rù Xué Shú Gè), which once served as a classroom. Poking your head in, you see an amassed array of teapots in cabinets. Walking around the lake and past the obligatory shop, you thread through an archway made of natural shaped stones into a leafy part of the garden. Taking up the centre of it is the pagoda-like Kui Xing Pavilion (魁星閣 Kuí Xīng Gé). In its bottom floor, a bust of Confucius smiles out at you. The 20-metre tall hexagonal tower was originally constructed in 1730 during the Qing Dynasty to worship the god Kuí Xīng (魁星). Kuí Xīng is the god of examinations and the servant of Wén Chāng Wáng (文昌王), the god of literature. The two gods are associated with the stars of the big dipper constellation. Six Chinese cedar wood (楠木 nán mù) pillars that stretch to the top of the tower are called the ‘pillars to heaven’. Ancient Chinese creation myths talk of the repair of the pillars of heaven that separate earth from sky, much like the universal idea of the axis mundi. The tower is also a reconstruction from the 1855 building work. You circle the tower, but cannot climb it and continue on to the other side of the gateway you saw across the courtyard from Míng Lùn Táng.

The first thing that strikes you is that the lions that guard the entrance are quite strange. They are so heavily stylised that they appear to be almost abstract. As normal with guardian lions, one is female and looks after her playful cub (symbolic of nurture) and the other male with a rattan ball in its paw (symbolising the emperor dominating the world). Confucianism preaches respect for authority, so the idea of an all-powerful ruler that must be obeyed is not an unusual concept to come across at a temple. The lions’ faces are the real unique feature. They are quite flat-featured and look as if they have been run into a wall. They are very artistically rendered and the carving of the scrolls of their manes is exquisite. On the verge of the gateway, you feel privileged to pass. This is the Study Gate (學門 Xué Mén), and in the past you would have had to have passed the imperial exam to cross it. The doorway immediately yields a stone-inlaid wooden screen and going around it, you stand in front of Rites Gate (儀門 Yí Mén), where your attire, being incorrect, would have hindered your progression into the central courtyard of the scholar route.

You exit through a side door to the entrance courtyard where your visit began and look back into the restored complex. It is a piece of Shanghai’s history that has been resurrected. It is an example of the cycle of things. As a temple it has been regenerated every century or so. It is a space that needs to exist, otherwise it would not have been continually replaced for more than 700 years. It is a central part of Old Quarter life and the small city within the metropolis requires its beating cultural and historical heart. As you depart you hope that it will not be destroyed again anytime soon and that it may inspire future generations of students to reach for excellence.

Nong Khai

Nong Khai

[…] Wen Miao, Shanghai […]