The seething masses form a human river at the main crossing in front of Sogo Department Store in the shopping mecca of Causeway Bay. People flock from all over the world to buy clothes and accessories in this commercial hub of Hong Kong. The neon lights and advertising really come to life at night, but for now, they lie dormant, waiting for the sun to set. Passing through the crowd, you break out into the less densely populated area near Victoria Park. Groups of Indonesian helpers congregate in groups in and around the park, eating food and generally making the most of their single day off.

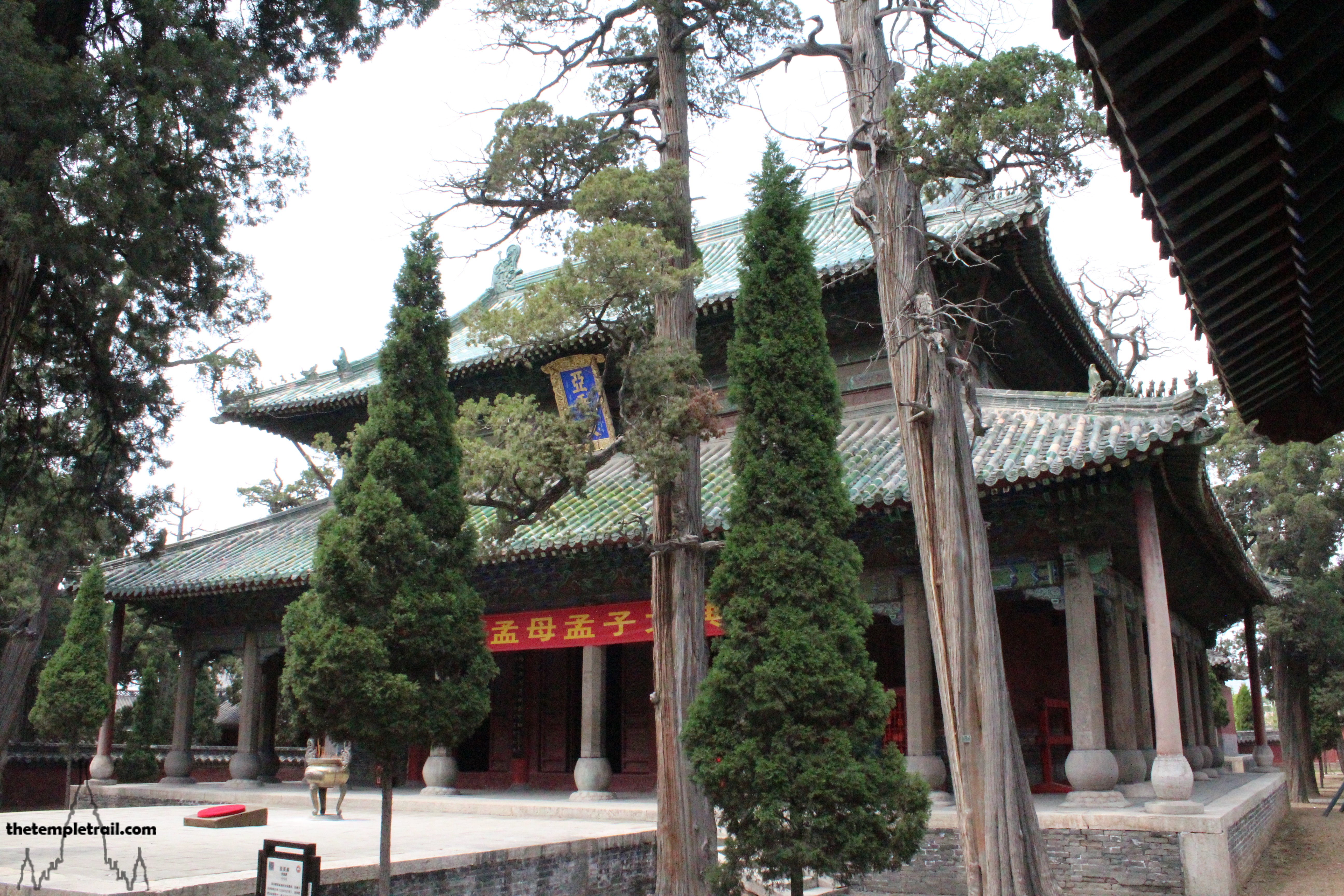

Passing a statue of the old British Empress for whom the park is named, you slingshot straight down the main road and find yourself in a different environment. No less urban than Causeway Bay’s shopping area, the neighbourhood’s MTR station is named Tin Hau, indicating to you that you are in the right neck of the woods. At a fork in the road, you veer right and terminate your journey in the grounds of an ancient temple, famous throughout Hong Kong. The Tin Hau Gu Miu (天后古廟 Tiān Hòu Gǔ Miào) in Tung Lo Wan is like a buried treasure chest. The layers of grime give it character, but underneath the smoke residue is a building filled with wondrous imagery just waiting to be found.

The temple was built by the Tai Clan in the early 18th century. The clan, Hakka people from Tam Shui in Guangdong, settled in Po Kong Village, before being evicted by the Japanese to build Kai Tak Airport on the Kowloon peninsula. The Tai used to gather grass across the water in Causeway Bay. They are said to have discovered a statue of Tin Hau (天后 Tiān Hòu) near the shore. They then built a shelter for the image which swiftly developed into a temple due to its popularity with the water dwelling groups of Hong Kong. The temple was renovated on a number of occasions over the years and a bell in the building has the date of 1747, showing that it had become a significant temple to the goddess by the mid-18th century. The building that stands today is the result of a major reconstruction in 1868, with some repairs done in 2004.

In 1897, a Crown Lease was issued to eight members of the Tai Clan following a lawsuit due to a family member trying to keep the temple profits for himself. Documents relating to the history of the temple were destroyed during the Japanese occupation. It is thanks to James Hayes of the Royal Asiatic Society of Hong Kong recording the oral history of an old woman of the Tai Clan in 1970, that this information is known. The temple is still managed by the Tai Clan some three centuries later and remains popular with the boat people of Causeway Bay. Management of the temple rotates through the eight branches of the Tai family on a yearly basis.

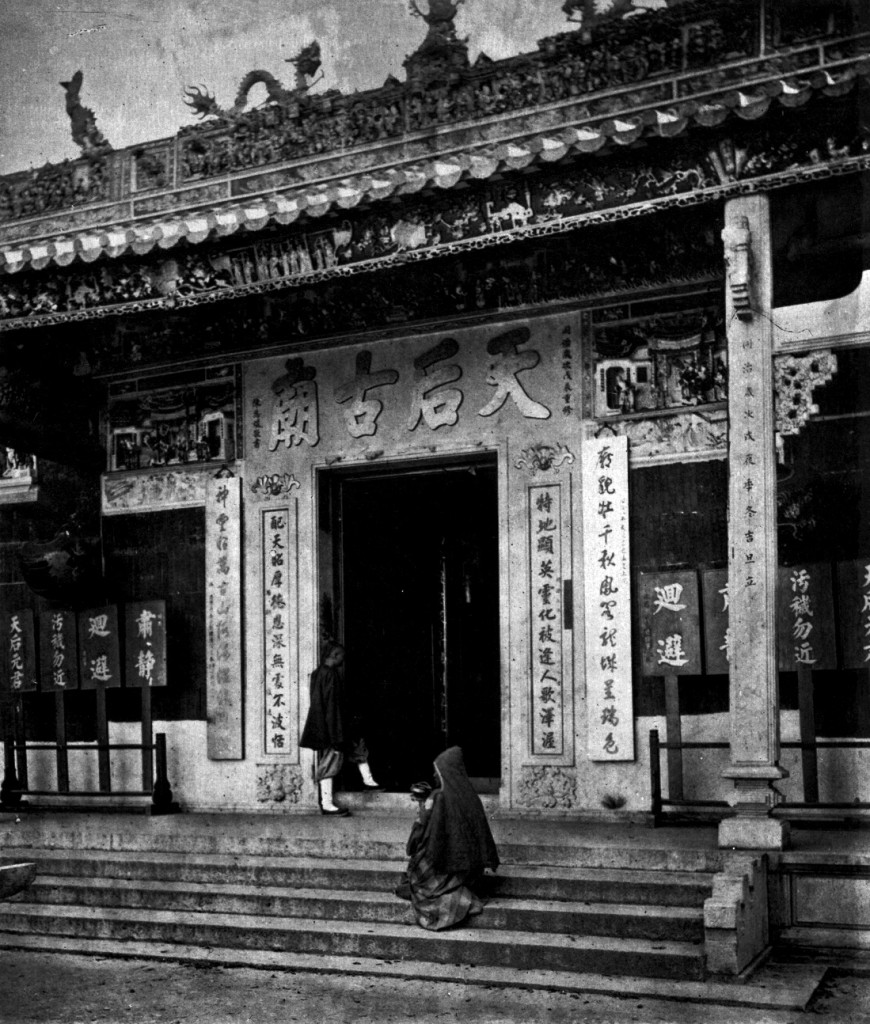

Standing at the entrance you are flanked by a pair of stone lions that were added to the temple in 1845. Behind you a brazier is speared with joss sticks which disperse their fragrance into the heavens. Ahead of you is the stone doorway famously captured in the 1870s by the lens on John Thompson, a famous pioneer photographer and one of the first to document East Asia. The eaves and ridge of the elaborate roof are filled with beautiful Shek Wan porcelain figures that seem to be swarming the upper section of the temple. Thompson mistakenly thought the temple to be dedicated to Kwun Yun (觀音 Guānyīn) and described the temple’s beggars preying on the charity of Buddhists. While he was not quite right about the temple, you find traces of his description ringing true, as some old ladies lift their begging cups towards you as you attempt to enter into the darkness of the temple. Dropping a few coins into their collections, you step forward and find yourself blanketed in blackness.

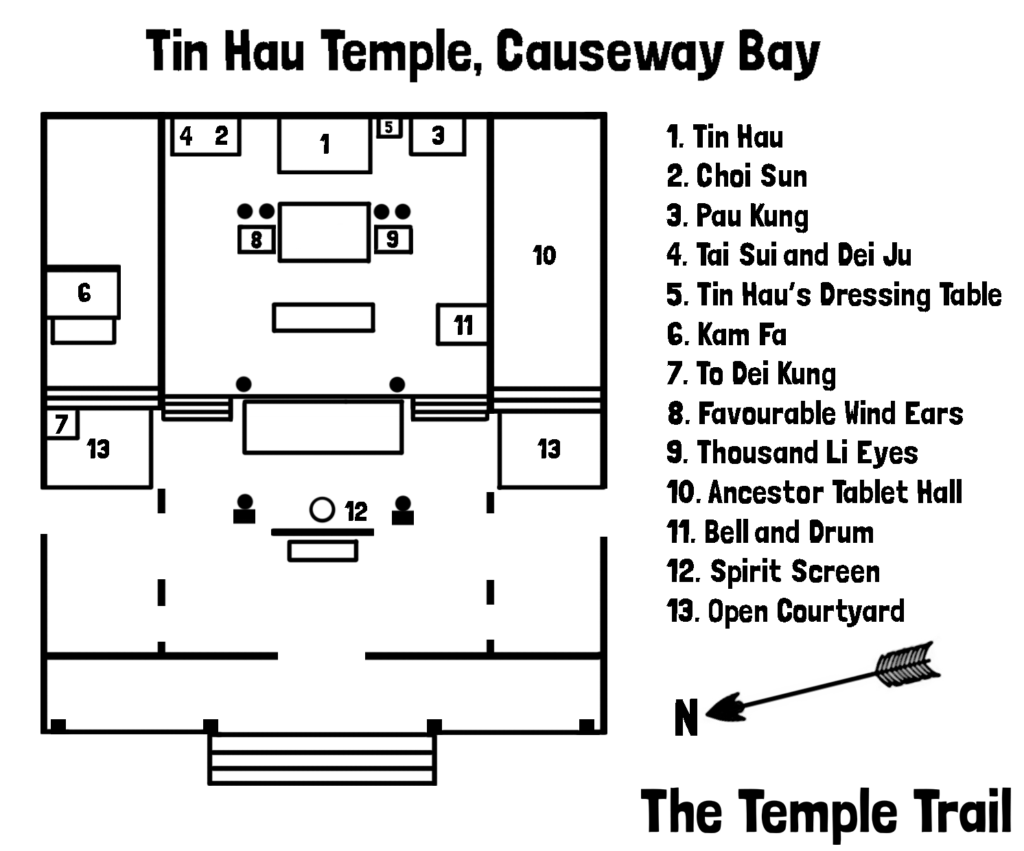

As your eyes become accustomed to the subtle lighting, you start to make out details of the temple. Here in the first hall, you face the dong chung (擋中 dǎng zhōng), or spirit doors, that keep the temple free of malignant spirits. Behind that an offering table holds two moodily lit “ti sum” votive pagoda light towers, adding an air of mystery to the space. The smoke filled chambers seem ancient and they have an atmosphere of being well-used over the years. The walls are blackened by the incense smoke of generations of worshippers and the only strong light penetrating the rooms comes from the front door and the two circular doors on either side of the first offering table.

Walking through the circular portal on the right, you find yourself in a courtyard with a pool for turtles. On the wall, above the container is a stucco dragon, decorated with porcelain shards. By the door, a furnace stand ready to receive the god money to send to the gods through ignition. Off the open courtyard is a side chamber and you poke your head in to look at the ancestor tablets contained within. Some members of the Tai Clan are remembered here and the room is filled with mostly empty tablet spaces interspersed with white tiles with a photograph of the deceased emblazoned on them. You backtrack into the main chamber and pass through the circular door on the opposite side.

The courtyard here contains a tiger to counter the dragon on the other side. The dragon is a yang creature, whereas the tiger is yin. The two forces balance the sides of the temple. From this courtyard, you see a soothsayer station to the left, connected to the main hall. The side hall on this side of the temple has an altar in the middle, cutting off the back of the room to the general public. The altar is crammed full of figurines, mostly of Kwun Yum, the Goddess of Mercy and Kwan Tai (關帝 Guān Dì), a god of war and fraternities. Obscured by the others, the main goddess of the chamber sits in the middle of the shrine. Kam Fa (金花 Jīn Huā) is the Golden Flower Goddess. She is a somewhat mysterious figure who is the patron of pregnant women. The goddess is often found in temples, but has her own dedicated spot on Peng Chau Island.

Back in the main hall, you skirt the left hand side and climb the short flight of stairs to the upper chamber where the main images of the temple are kept. On the left hand wall, a set of pictures and a statue represent the Tai Sui (太歲 Tài Suì). The Tai Sui are sixty gods who in turn govern one year in a sixty year cycle. The year you are born in affects which Tai Sui impact negatively on you in the current year. Through a complex system of divining, you need to appease the right ones to ensure that you don’t have any bad luck. By the sixty gods on the far wall of the temple is the first of the three main altars of the hall. This one is dedicated to Choi Sun (財神 Cái Shén), the God of Wealth. There are many legends relating to the God of Wealth that appear at odds with each other. This is due to him being a composite figure of various different wealth deities and folk figures that have come together to make Choi Sun. The dark statue before you is bedecked in colourful robes that stand out in the moodily lit booth.

From the God of Wealth, you move to the centre of the hall. Behind a large granite offering table that dates from the 1860s, the main altar of the temple contains the goddess. In front of the table, two demons flank Tin Hau, protecting her from those who would do her harm. On the left is Shun Fung Yi (順風耳 Shùn Fēng Ěr), or Favourable Wind Ears and on the right is Chin Lei Ngan (千裡眼 Qiān Lǐ Yǎn), or Thousand Li Eyes. These two sea demons fell in love with Tin Hau, but she tamed them, leading them to become her faithful bodyguards. Passing these two sentinels, you walk around the offering table and come close to the main shrine of the temple and Tin Hau, who looks out from it.

Tin Hau means Empress of Heaven, but it wasn’t always so. She was born as a mortal on Meizhou Island in Fujian Province in about 960 CE. Her name was Lín Mòniáng (林默孃) and she lived as a normal girl. She studied Taoist arts and Buddhism and began to gain powers. When her father and brothers were caught out at sea in a typhoon, she went into a trance and saved them. At the age of 27, she died and ascended to heaven, where she quickly rose among the ranks. On her native island she became known as Māzǔ (Grandmother Ancestor) and soon here following grew and spread out throughout China. Emperors bestowed titles upon her until she eventually became Tin Hau, the Empress of Heaven and patron of seafarers.

Looking in through the glass, you see the statue that the temple was built around. Darkened by time and smoke, the image has been enthroned here by the Hakka for over two and a half centuries. The power radiating from the statue is tangible and Tin Hau’s presence is felt throughout the temple. Leaving the space between the altar and table, you move over to the right and the third altar. Here, another dark figure looks out at you. The god Pau Kung (包公 Bāo Gōng) is almost always pictured with a black face. Known as Justice Pau, he is an underworld god who fairly judges the deceased. In life he was an upstanding magistrate in Kaifeng during the early Song dynasty (960 – 1279 CE). When he died, the people loved him so much, that they prayed to him for justice, believing that his powers continued after death.

On the right hand wall next to Pau Kung is a shrine with a statue of two boys together. These two are the Wo Hap Yi Sin (和合二仙 Hé Hé Èr Xiān), Immortals of Harmony and Union. These two are often associated with happy marriage and friendship and shown symbolically holding a lotus flower and a box. The two child immortals can actually trace their origins to a pair of semi historical figures from the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE). Two Buddhist poet monks, Cold Mountain (寒山 Hánshān) and Foundling (拾得 Shídé) were close friends who worked in the kitchen of Guoqing Temple on Mt Tiantai in Zhejiang Province. They are often considered to be emanations of Mañjuśrī (文殊 Wénshū) and Samantabhadra (普賢 Pǔxián), two Buddhist bodhisattvas. They are often depicted with their friend, the monk Big Stick (豐干 Fēnggān), who also composed poetry. The poems of Hánshān are particularly famous, even if the writer may not have actually existed. Over time, the Taoists adopted the two and they took on a new persona and were depicted as two young boys.

As you make your way out, you pass the bell that was cast in 1747. An Antiquities and Monuments Office information plaque that tells of the bell’s date, also gives an alternative legend regarding the founding of the temple that doesn’t match the oral history from the old lady of the Tai Clan back in the 1970s. It states that the temple was built after a red stone shaped like an incense burner was found floating at sea by the family. Believing it a gift from Tin Hau, they built the temple to enshrine it. A sign outside gives a slightly different story again and also says that this is the reason that one of the pre-colonial names of Hong Kong was Hung Heung Lo (Red Incense Burner Island). The story just adds to the confusion and mystery surrounding the temple’s foundation and shows how time changes all things, especially legends.

Stepping out through the stone doorway, you look across to the tower blocks that now obscure the sea. This temple once stood next to the waves crashing against the rocks where statue was found so many years ago. Land reclamation and development have led to the temple being segregated from the ocean and the goddess is a little removed from her home. Standing in the forecourt of the temple, you gaze back at the ancient building. It is one of the most authentic temples in Hong Kong. The atmosphere, both inside and out are awe inspiring. When you are in its vicinity, you feel in the presence of something powerful and enigmatic. Perhaps it is the weight of history that rests upon its joists, or maybe it is Tin Hau’s potent energy that makes this temple a portal to another world.

Yi Shing Temple

Yi Shing Temple