The dreary unrelenting rain continues to pour down as you get off the metro in a non-descript and run-down looking area of Taipei. The Taiwanese capital has seen better days and it is noticeable in this area that was once the Dalongdong village. The ancient village area lies between the Keelung and Tamsui Rivers was formally incorporated into Taipei during the first half of the 20th century Japanese occupation of Taiwan and looks like not much has been done to develop it in the following years. The gunmetal grey skies and consistent rainfall do little to elevate the area in your estimates, but something beautiful has drawn you here. Like a diamond in the rough, a fabulous temple, one of two in the area, lies waiting to be discovered amid the more modern drudgery of architecture. Alongside the famed Dalongdong Baoan Temple, stands another great temple of the area. The roof of a stunning temple peaks out over the wall that encircles it. Turning the corner and heading for the western entrance, you pass through the barrier wall and land in the compound of the Taipei Confucius Temple (臺北孔子廟 Táiběi Kǒngzǐ Miào).

Originally built between 1879 and 1884. When Japan went to war with China in 1894, Japanese soldiers occupied the temple while putting down the Taiwanese resistance movement. They damaged and destroyed the memorial tablets and the temple fell out of use. It was eventually torn down in 1907 in order to build the Taipei First Girls School. After many years of campaigning, the local Taipei gentry raised funds and bought a new piece of land. They engaged the services of the famous Fujian master temple builder Wang Yi-shun (王益順 Wáng Yìshùn), who also worked on the Manka Lungshan Temple a few years earlier. Work began in 1927 and the main buildings were completed in 1930. The Min Nan styling of the buildings reflects Wang Yi-shun’s work as the chief engineer. Wang Yi-shun returned to his native Quanzhou and there was a hiatus in the construction as funds had dried up. In 1939, the auxiliary buildings of the temple were finished by local Taiwanese builders. While not on the same scale, the Taipei Confucius Temple is modelled on the Temple of Confucius in the sage’s hometown of Qufu (曲阜 Qūfù) in Shandong Province. When the Second World War broke out, the Japanese colonial government ordered an end to the Chinese ceremonies and Shinto ritual music replaced the traditional Chinese performances until the Republic of China regained control of Taiwan in 1945. Now, as then, ceremonies are carried out on the 28th of September every year. Highly ritualised traditional music and dance are used to honour the Master.

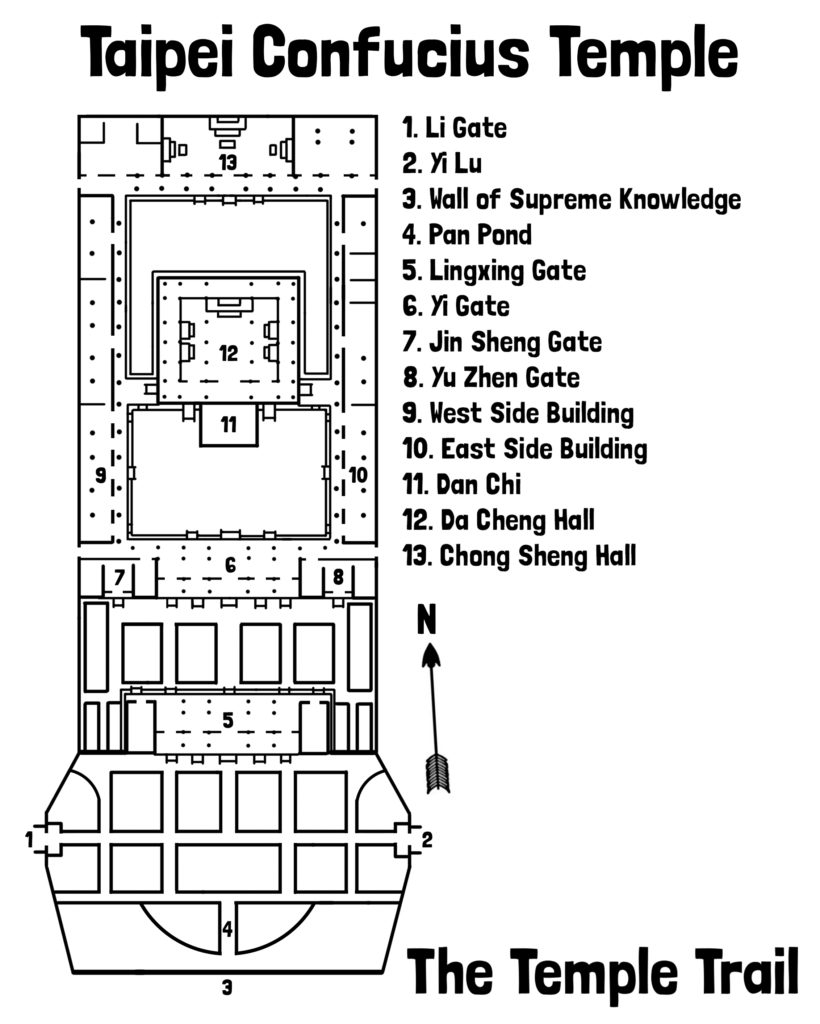

Entering through the Gate of Learning (黌門 Hóng Mén), you pass the newest structure of the compound, the Hall of Moral Instruction (明倫堂 Míng Lùn Táng). Added in 1956, this rather utilitarian looking building acted as a school and some special classes and lectures are still held there. Bypassing the building you head straight for the Gate of Rites (禮門 Lǐ Mén). You pass through the simple gate and into the first courtyard area of the temple. The front of the space is on your right as you enter and is dominated by the Wall of Supreme Knowledge (萬仞宮牆 Wàn Rèn Gōng Qiáng). This wall acts as a spirit screen and is emblazoned with a Chinese Unicorn (麒麟 qílín). This auspicious animal is said to appear before sages are born and, according to legend, one materialised before Confucius was born. The wall itself is deeply symbolic. It represents the profundity of the teachings of Confucius. It shows that you cannot easily gain the knowledge and that you must strive hard to learn. This is further reinforced by the fact that you must enter through the Hóng Mén, as you have done, or the opposing School Gate (泮宮 Pàn Gōng), rather than directly entering the temple from the front.

In front of the wall is the School Pond (泮池 Pàn Chí). This semi-circular pool is crossed by an arched bridge. The pond has geomantic properties as well as a practical cooling effect during the summer months. There is no need to cross the bridge, but in imperial times, the bridge could be crossed only if the area had produced a first ranked scholar (狀元 zhuàngyuan) in the Imperial Examination (科舉 Kējǔ). Here in Dalongdong, there is a house marked by a stone flagpole. The home of Teacher Chen Wei-Ying (陳維英 Chén Wéiyīng) was granted the pole and flag of office, as he gained the rank of advanced scholar (進士 jìnshì). The scholar who ranked second in the imperial exam in the province in 1895 became an important educator in Taiwan. From where you stand, you look directly through to the right side of the temple and see the two gates which mirror those through which you walked. The nearest gate is emblazoned with the words “Path of Righteousness” (義路 Yì Lù) and the further gate is called the Pàn Gōng (School). The side gates, Hóng Mén and Pàn Gōng, represent two ancient schools of China and the Lǐ Mén and Yì Lù constitute the first two lessons of Confucianism; rites and righteousness.

Turning to your left you stand on the central axis of the temple and ahead of you stands the Top Scholar Star Gate (櫺星門 Líng Xīng Mén). The impressive gateway is capped by a beautiful double-eaved hip and gable roof. The ceramic mosaic (剪黏 jiǎnnián) figures and creatures play along the top of the roof and two intricate coiled dragon (蟠龍 pánlóng) columns help support it. Stepping up to the front of the central doorway, you examine the skilled artisanry of the stonework. Made from white stone, the columns were quarried in Quanzhou. Between the two columns are the closed central wooden doors. As only a top scholar should be able to pass through them, they are shut to you. Covered with 108 decorative golden studs rather than with door god images, the studs act, alongside the eight trigrams (八卦 bā guà) painted onto the roof beams, to expel demons and protect temple from evil forces. There are two circular spiral-carved drum-shaped bearing stones (石鼓 shí gǔ) on either side of the door to show the status of the building and add extra spiritual protection. You note that there are no rhyming couplets (對聯 duì lián) on each side of the door as is normal in Chinese temples. This is because one should not flaunt ones literary prowess before the Master. Nobody dares try to try and outshine Confucius in terms of writing.

Confucius is known as Kǒng Zǐ (孔子) or Kǒng Fūzǐ (孔夫子) in Chinese and was born in the State of Lu in 551 BCE. Raised by his widowed mother he took up menial work despite being of a moderately high class. Due to his diligence, he climbed the ladder and held various ministerial posts in his lifetime. After leaving his home state of Lu, he wandered through central and northeastern China teaching, rather unsuccessfully, his moral system of governance. He gained followers, but no one who could influence the affairs of state. After his death in 479 BCE, his students and the lineage that followed them managed further Confucianism during the Hundred Schools of Thought era (6th century – 221 BCE). Suppressed during the Qin Dynasty (221 – 206 BCE), it had major revivals during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE) and Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 CE) where it mutated and incorporated metaphysics, cosmology and elements of Buddhism and Taoism. The ethical core of Confucianism is a strong belief in meritocracy and the Mandate of Heaven. It promotes the behaviour of a superior person (君子 jūnzǐ), the Five Constants (五常 Wǔcháng – humaneness, righteousness, proper rite, knowledge and integrity) and The Four (四字 Sìzì– loyalty, filial piety, continence and righteousness). A Confucian should be honest, forgiving, neat, brave, kind-hearted, reverent, frugal and modest. Confucius’ values of simplicity are echoed throughout the temples build to honour the Great Sage. As you opt to take the doorway on the left through the Líng Xīng Mén, you see none of the elaborate decorations that you find in other Chinese temples.

The next courtyard brings you one step closer to the First Teacher, but before you can see him, you must pass through Etiquette Gate (儀門 Yí Mén), also known as Great Accomplishment Gate (大成門 Dà Chéng Mén). This much-simpler gate is closed out of respect to Confucius and is only opened during ritual ceremonies. The doors are plain, but intricately carved wooden screen windows which are brightly painted occupy the spaces on both sides of the central doors. There are eight of these colourful panels across the five-room wide gate, but the central panels, depicting eight hornless dragons (螭 chī) arranged around a censer, are the most renowned. It is the largest gate and it opens out onto the main sanctuary of the temple, but its simplicity belies this fact. Its simple architecture actually mimics that of the main temple of Confucius in the Sage’s hometown of Qufu. Looking up at the roof of the gate, you note that it is single-eaved, but features hornless dragon mouth gargoyles (螭吻 Chīwěn). These fish/dragon hybrids are often placed on the roof ridges of important buildings as they like swallowing and consume all evil influences. They stifle evil air, prevent fires and are powerful talismanic forces. The Chīwěn are one of the nine sons of the dragon (龍生九子 lóng shēng jiǔ zǐ). These creatures are used decoratively in elements of Chinese art and architecture depending on their properties.

On either side of the main gate are the Golden Sound Gate (金聲門 Jīn Shēng Mén) and Jade Vibration Gate (玉振門 Yù Zhèn Mén). These are open and used for normal passage. The golden sound refers to a bronze bell and the jade vibration refers to a sounding stone (磬 qìng). The bell was rung at the beginning of a musical recital and the stone struck at the end. The names of these gates is a play on the words of the great Confucian scholar Mencius (孟子 Mèng Zǐ) who said ‘start with the bell and end with the chime and the music will be perfect’. This is an idiomatic way of talking about scholarly subtlety and refers to a clear and meaningful lesson. You opt to take the Jīn Shēng Mén on the left so as to begin your lesson with the Great Sage. Entering, you find yourself in the corner of the main courtyard and sanctuary of the temple.

In the centre stands the Hall of Great Accomplishment (大成殿 Dà Chéng Diàn) and it is flanked on each side by the East Side-building (東廡 Dōng Wǔ) and the West Side-building (西廡 Xī Wǔ). These long, low roofed buildings contain the wooden tablets of 154 Confucian scholars. Approaching the West Side Building, you peer in at the tablets of 39 disciples and 38 scholars of later periods. The row of illuminated plaques extends the length of the simple hall. Crossing the courtyard, you see that the East Side Building has a similar arrangement with 40 disciples and 37 later scholars. The last scholar to be enshrined, was the teacher Chen Wei-Ying, whose home is marked by the stone flagpole of an advanced scholar. The beloved local educator was enshrined in 2006. After looking in on the followers of Confucius, you make your way towards the Dà Chéng Diàn to see the Master himself. The hall is the largest and most elaborate of the temple complex. Five rooms wide by six deep, the hall has 42 Quanzhou white stone columns supporting the double-eaved roof that covers the corridors on each of the four sides of the hall.

The roof of the hall strikes you. It is richly ornamented with Chīwěn, lions, horses and an array of other creatures including four Cháofēng (嘲風). Another of the sons of the dragon, these goat-dragon hybrids like precipices and protect the roofs of buildings. 72 unfilial birds rest on the diagonal ridges to show that even evil birds will submit to the wisdom of the Sage. It is the central pagoda and the cylindrical roof ridge features that really grab your attention. The seven storey pagoda suppresses evil and therefore sits in the centre of the ridge. The two cylinders on each side of the ridge rest on the backs of turtle-dragon hybrids called Bìxì (贔屭), yet another of the dragon’s sons. The cylinders are decorated with dragons and are of immense symbolic importance to Confucians. Known as heavenly interface canisters (通天筒 tōng tiān tǒng), these decorations were first introduced to Confucius Temples by the important rationalist Neo-Confucian scholar Zhū Xī (朱熹) in the late 12th century CE. They are said to represent secret containers designed to protect books during the Qin Dynasty. The first Emperor, Qín Shǐ Huáng (秦始皇), in an attempt to keep his people illiterate, suppressed knowledge and burned books. The Confucians suffered greatly in this time and these book-hiding barrels were created to look like chimneys. Books were placed inside and they were then mounted on the roof so as to escape detection. Tiān is a very important concept in Confucianism. Translated, it means heaven, but the deeper meaning is that of the Great Whole and is somewhat like Tao (道 Dào) in Taoism. It is the ultimate source of reality.

Walking up to the Dà Chéng Diàn, you first come to the raised platform (丹墀 dān chí). This is used for ceremonies involving music and dance and is a common sight in Confucian temples. In front of the platform is an imperial road (丹陛石 dān bì shí). The stone with a cloud dragon carved into it is normally flanked by steps, but here it, unusually, stands alone. Climbing the steps by the platform, passing two coiled dragon columns, you come the door of the hall and look inside. As your way is blocked by a rail, you gaze in and allow your eyes to adjust to the darkened interior. It is filled with an array of musical instruments from ancient times, including a set of sounding stones (編磬 biān qìng), a cloud board (雲板 yúnbǎn), a set of Bronze bells (編鐘 biān zhōng), a large bell (甬钟 yōng zhōng), large drum (晉鼓 jīn gǔ) and a tiger-shaped wooden percussion instrument (敔 yǔ). In the Analects, Confucius considers elegant music (雅樂 yǎyuè) to be beneficial, so this ancient form of music from the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046 – 256 BC) remains an intrinsic part of Confucian ritual.

Amid the strange looking instruments, in the centre of the hall and in a high altar is the memorial tablet of Confucius. The Master is not represented with a statue and neither are any of the other scholars here. It was usual for Confucius to be represented by a statue until the reign of Hongwu, the first Ming emperor (1328 – 1398 CE). Emperor Hongwu (洪武帝 Hóngwǔ Dì) disliked the different representations and issued a decree that all new temples could only use memorial tablets rather than statues of Confucius. The eleventh Ming emperor, Jiajing (嘉靖帝 Jiājìng Dì) decreed that all existing imagery inside halls be replaced by tablets. While this rule generally applies, there are a few exceptions such as Wen Miao in Shanghai, which has a statue of the sage rather than a tablet in the main hall and Fuzi Miao in Nanjing which has a painting.

On the left and right walls are shrines to the Four Sages (四配 Sì Pèi) and Twelve Philosophers (十二哲 Shí’èr Zhé). The Sages are Yán Huí (顏回), Zēng Zǐ (曾子), Zǐsī (子思) and Mencius. They were four very important Confucians with saint-like status. The Twelve Philosophers were twelve great Confucian thinkers who rank just under the Four Sages. Above the main altar hangs a black calligraphic plaque written by Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí), leader of the Republic of China from 1928 until his death in 1975. It reads ‘Education without Discrimination’. In the centre of the ceiling is an octagonal plafond recess with four bats (四蝠 sì fú), a homonym for ‘giving fortune’. Walking around to the back of the hall, you find an old decommissioned painted beam on a mount with a bā guà painted in its centre. This was originally part of the final hall on your route. You jump down from the elevated platform and head to the last hall of the temple.

At the back of the complex is the Esteemed Sage Ancestral Hall (崇聖祠 Chóng Shèng Cí). In the shrine, you see more memorial tablets. These are for five generations of Confucius’ ancestors who preceded him, his brother Mèng Pí (孟皮), the fathers of the Four Sages and of other important Confucian scholars’ fathers. This is a demonstration of the important Confucian ethics of filial piety and rites. Confucian temples often closely follow ancestral halls in layout. In Chinese culture, the veneration of ancestors is vitally important to the success of the current and future clansmen. Ancestral halls (宗祠 Zōng Cí) are built to act like temples so that ancestors’ spirits can be appeased and that they are provided for in the afterlife.

Walking back through the complex, you pass through the Yù Zhèn Mén, thus ending your lesson in Confucian ethics. Strolling back through the grounds, you contemplate the traditional ideology of Confucius and how it has carried forth to this day despite many setbacks and rival systems. It has outlived the once powerful Legalism and its staunch opponent Mohism. Something about the culturally rooted system of thought remains deeply rooted in the Chinese psyche. It has an attraction to the Chinese people that cannot be shaken. Pondering the lesson you received from the temple, you exit and continue to wander through the Dalongdong neighbourhood and towards the famous Baoan Temple.

Chinese New Year in Hong Kong

Chinese New Year in Hong Kong