Strolling around the eastern part of Hong Kong Island, you feel far removed from the busy life of Central and Causeway Bay. In Shau Kei Wan, the neighbourhood feels very local. Having taken in the Tam Kung Temple by the old water’s edge, you take a very short diversion to the former village of Ah Kung Ngam. Now a residential area cut off from the town part of Shau Kei Wan by some light industry facilities, the village has a small, but interesting temple. After a couple of minutes’ walk, you see a diminutive little temple on the corner of the street. Little bigger in size than an Earth God shrine, it actually houses the god at the top of the celestial hierarchy.

The single room temple rests on a red painted pavement corner. Approaching the curb, you note the distinct lack of traffic and the quiet feeling of the neighbourhood. It is an area that is in limbo between industrial and residential use. Yuk Wong Temple is well maintained and much used by the local residents. Built sometime in the 19th century by migrants from Huizhou and Chaozhou who came to quarry stone in the area, the small temple became popular with the local fishermen. Standing on the red kerbside, you note the well-worn red furnace filled with still smouldering embers.

Next you the door, a small shrine to Dai Bak Kung (大伯公 Dàbó Gōng), the Protector Earth God, occupies a tiny space on the ground. Passing the two door gods, you enter into the little chamber that houses the powerful Yuk Wong (玉皇 Yù Huáng), the Jade Emperor. It is surprising that such an important deity has such a small temple, but temples to the Jade Emperor are a rarity in Hong Kong. To either side of Yuk Wong are Tin Hau (天后 Tiān Hòu), the Empress of Heaven and Kwun Yum (觀音 Guānyīn), the Goddess of Mercy. In the central altar, the golden statue of the Jade Emperor waits to hear the petitions of worshippers. When Hong Kongers pray to other gods, they ask them to petition Yuk Wong on their behalf. Here, this temple offers them the rare opportunity to ask for their wishes directly to the top deity.

After a few moments in the chamber, you leave and start to walk into Shau Kei Wan proper to visit a larger temple. Along the road into the town, you Pass an old Tin Hau Temple and make a note to return to it on your way back to the MTR station later. Passing old people sitting about in the shade and talking with one another, you take in the small town feel of the district. Soon, you find a walled, shady space that many of the older people are sitting outside. Walking up to the gates, you enter into the sanctuary of the Shing Wong Temple.

Originally built in 1877, the temple was then known as Fuk Tak Tsz. The name refers to the worship of the local district god. Fuk (福 fú) means good fortune and tak (德 dé) means virtue. The Righteous God of Virtue and Blessing – Fuk Tak Zeng San (福德正神 Fúdé Zhèngshén), or simply Fuk Tak Kung (福德公 Fú Dé Gōng), Lord of Fortune and Virtue is often mistaken for To Dei Kung (土地公 Tǔ Dì Gōng), the Earth God. To Dei Kung is the local wayside earth god and each area has one. Fuk Tak Kung is almost indistinguishable from To Dei Kung and even locals confuse them, which happened in this temple. The temple was originally used to pray to Fuk Tak Kung or To Dei Kung, but in 1974, it was upgraded and the main deity along with it.

Before entering the actual temple, you walk around it to see a small shrine the right of the main building. An ancient carved stone stands upright in the small courtyard. Older than the temple that grew next to it, it reads Bun Fong She Jik Zeng (本坊社稷正 Běn Fāng Shè Jì Zhèng). It roughly translates to this is the place of She Jik, ancient gods of soil and grain. In this case the gods are acting as wayside deities that protect the local area and its agricultural interests. These predecessors of the Earth God, To Dei Kung, show how the area developed to need increasingly higher level deities to serve it. In Beijing and in Seoul, the state altars to soil and grain still stand today and were used in grand imperial rituals employed to ensure a good harvest. This small scale shrine may not have the grandeur of the large altars, but it draws the local people who still feel a connection to the primal spirits.

Walking back to the front, you see that opposite the entrance door is another written marker stone, this time painted red. It reads Tin Gun Chi Fuk (天官賜福 Tiān Guān Cì Fú), meaning the Heavenly Officer bestows fortune. This tablet can also traditionally be found in households and refers to a non-specific god and general hopes for fortune. Turning about on your heels, you face the front door. The building you see before you is in fact a shell that covers the older temple within. When the temple was expanded in 1974, the decision was taken to install a god at the next level up on the heavenly bureaucratic ladder.

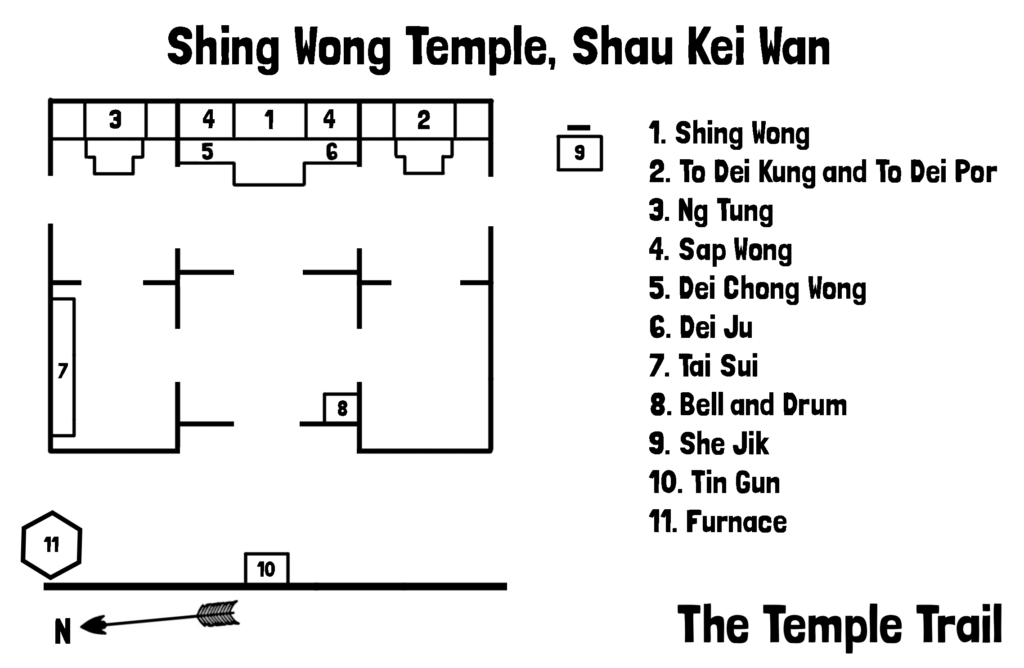

Walking in to the newer section of the temple, you find yourself in an unusually empty space. Rather than having imagery filling the antechamber of the temple, there are stacks of joss items for burning. The original three chambers of the temple had three more added to the front. From the central of these, you explore the antechambers on the left and right. The hall on the right is similarly devoid of gods, but the left hand side hall has a shrine to the Tai Sui (太歲 Tài Suì). The sixty gods that take turns in governing a year in the sixty year cycle are not benevolent and god money has been placed under some of them to appease them. In the centre of the group of gods, Dau Mo (斗母 Dǒu Mǔ), the Goddess of Measurement determines when each god’s watch is over.

Returning to the middle room, you stand before the original entrance to the temple. Now adorned with a boat shaped choi mun (彩門 cǎi mén), the stone doorframe that once operated as the front door to Fuk Tak Tsz is now in the middle of the building. The original temple name is obscured by the choi mun, but the Deoi lun (對聯 duìlián) rhyming couplets are still clear on each side of the door. At the top of the line of poetry on the right is the character fuk and the top of the left is tak, identifying its original dedication.

Passing through the door, you come into the older section of the temple. Before looking in detail at the central chamber, you take the door on the right and investigate the room that it leads to. This section of the temple has an altar dedicated to the main Earth God, To Dei Kung, and his wife To Dei Por (土地婆 Tǔ Dì Pó). The elderly couple are carved from wood and sit on thrones. Once the main object of veneration, the Earth god has been shifted from the main hall to the side in order to make way for his superior officer. Still powerful in local affairs, the offering table is filled with lamps and incense.

Leaving the chamber, you pass through to its mirror on the far left of the temple. Here, you are in the presence of the Ng Tung (五通 Wǔ Tōng). These are the Gods of the Five Lucks. In Chinese culture five types of luck are held very dearly. The Ng Fuk (五福 Wǔ Fú), Five Lucks, are longevity (長壽 cháng shòu), riches and honour (富貴 fù guì), health and peace (康寧 kāng níng), good morals (好德 hǎo dé) and virtuous death (善终 shàn zhōng). The five figures peer out from their shrine attentive to the prayers of those wishing to gain their services. Their dark visages create an air of mystery and looking at them, you see the potency of what they offer to the faithful.

From this room for the fortunes of the living, you move to the central chamber, one geared very much towards the welfare of the dead. In the central altar sits the main god of the temple, Shing Wong (城隍 Chénghuáng), the City God. In the past, every major city in China had a city god temple, but the 20th century saw the demolition of countless numbers of them along with too many other religious buildings. The City God originally bore responsibility for the walls and moat of the old cities. Shing Wong gradually moved out of this role into ruling over the dead of a city. This explains the piles of joss items in the antechamber. These paper items will be burned, in order to send their essence to the deceased relatives of the local people. By burning paper money, the sum is received in ‘hell’ by the dead ancestors. Hell is a word used to describe the afterlife and does not carry the purely grim meaning that it does in Western culture. Hell is a place where the spirits of the dead can go about afterlife very much the way they did in their actual life. A constant supply of goods is needed, however, in order to keep the dead happy.

Shing Wong is in charge of keeping an eye on the dead, so it is in his temple that the main activities regarding offerings to ancestors take place. Looking at the bearded figure swaddled in a yellow robe, you feel his searching stare and the power in his dark eyes. On the table in front of him, the photo of a recently deceased man rests, under the benevolent protection of the god. The living relatives of this man have placed his photo there in the hopes that, after some petitioning to the god, his spirits will be at peace. Traditionally, the Chinese believe in two types of soul, the wan (魂 hún) and the pak (魄pò). The wan is the spirit which ascends and can occupy a spirit tablet on the family altar. The pak descends with the body and is the more physical of the two types. The important thing is to keep these ancestral spirits on side and fighting on your behalf in the spirit world.

To the left and right of Shing Wong are the Sap Wong (十王 Shí Wáng), the Ten Kings of Hell. Represented by plaques here, the ten judges decide the fate of those under their care in the next life. Each of them rules over one of the Sap Din Jim Lo (十殿閻羅 Shí Diàn Yán Luó), or Ten Palaces of Hell and nine are deputies to Yim Lo Wong (閻羅王 Yán Luó Wáng), the supreme Ruler of Hell. The ten kings are Chun Gwong Wong (秦廣王 Qín Guǎng Wáng), Tso Gong Wong (楚江王 Chǔ Jiāng Wáng), Sung Tai Wong (宋帝王 Sòng Dì Wáng), Ng Gun Wong (五官王 Wǔ Guān Wáng), Yim Lo Wong (閻羅王 Yán Luó Wáng), Bin Shing Wong (卞城王 Biàn Chéng Wáng), Tai San Wong (泰山王 Tài Shān Wáng), Dou Si Wong (都市王 Dū Shì Wáng), Ping Dang Wong (平等王 Píng Děng Wáng) and Jun Lun Wong (轉輪王 Zhuǎn Lún Wáng). These infernal bureaucrats look over the shoulder of Shing Wong and listen to the pleas of the living for their ancestors who have passed into the next realm.

You look under the altar to the five kings on the left and see that the ha tan (下壇 xià tán), or lower altar, contains a statue of Dei Chong Wong (地藏王 Dì Zàng Wáng), the Buddhist Earth Treasury Bodhisattva. The Buddhist saint is responsible for the hells also. His counterpart on the right-hand side at floor level is Dei Ju (地主 Dì Zhǔ), an earth god, represented by a tablet. The theme of earth and the afterlife is reinforced over and over again in the temple and feeling ready to return to the land of the living, you exit the chamber and back into the daylight of Shau Kei Wan.

All around you, life is acted out by the people of the area. The elderly seem to enjoy the shade around the outside of the temple grounds. It is as if they are putting in some groundwork with the god who will ultimately determine their future after they transition from this world to the next. Having come face to face with the gods of death and the gods of the earth, you too feel as if you have gained some connection with the land and eternity. With this experience, you travel back through the non-stop work and play of modern day Hong Kong, where there is a disconnect from both of these elements.