Your plane from Santiago touches down on the dusty tarmac and the airbrakes begin to wrench you to a halt. The summery southern hemisphere January that you left in the blue-skied capital, is not quite so apparent here. From sea level, you have arrived at the high altiplano of the Atacama Desert. Stepping from the plane, you immediately feel the cool aridity and you rush to put on your jacket. The thin air leaves you a little breathless, but still capable of walking fast enough to stay warm. The sky is an unexpected steel grey and the weather forecasts flying around among the Chilean passengers are for the very rare occurrence of rain. The Atacama, the driest place on the planet, is expecting some torrents.

The minibus from the airport takes you through alien landscape. Low-rise adobe buildings begin to take shape in the distance. This is one of the last towns in Chile before you get to the Bolivian border. San Pedro de Atacama sits on the Puna de Atacama, a high plateau oasis that has supported human life since the Atacameños settled here 4000 years ago. Pulling into the desert town, you settle in your guesthouse before exploring on foot. The ominous clouds that have been threatening to drop their payload skirt along the sky. Rain in the desert is hazardous. The hard compacted-earth streets turn into rivers and mudslides become a real danger.

Pretty mud brick buildings line the unpaved, unmarked streets and the sun peaks through the clouds to heat up the area a little. As you meander aimlessly, it is only a matter of time before you arrive at the centre of the small outpost town. On the Plaza de Armas, the tallest structure takes centre stage. The Iglesia San Pedro de Atacama is said to be the second oldest church in Chile, but its exact date of construction is unclear. Evidence suggests that a mission chapel of St Peter was located by the cemetery here in the mid-16th century and a plaque at the church states that mass was given to the local Kunza speaking Atacameños by the presbyter Don Cristóbal Díaz de los Santos in 1557.

The current building is mostly from the mid-18th century and is a beautiful little whitewashed adobe church. The structure is made of local trees called chañar and algarrobo. The now endangered cardón cactus-wood is also used in the structure. It is slung together with lama-hide leather straps, covered in adobe. The soft lines of the walls are highlighted by the blue arched doorways and stepping through the gate of the churchyard, you approach the front door and enter the building.

Feeling safely sheltered inside the church, thoughts of the impending downpour leave your mind. The church is surprisingly light inside. The whitewashed interior reflects the light and the thick walls keep the church cool. Walking slowly up the nave the smell of the moisture in the air mingling with the dust hits your nostrils. To your right the old church bell rests on the floor. It is inscribed with the date 1607, indicating that it was cast for an earlier incarnation of the church. The bare wooden beams of the roof stand out from the white walls. The church has been rebuilt and reconstructed many times and has been born again like a phoenix from the flames of the many fires that have racked the building. This, perhaps, is the great danger of the arid desert environment.

Coming to the end of the nave you stand looking at the colourful chancel. The humble church architecture here harks back to its origin as a missionary chapel and there is no apse. The altar, however, sits in front of a bright blue and white reredos that more than makes up for the simplicity of the church structure. Amid other saints, San Pedro takes pride of place in his priestly vestments below a depiction of the virgin. The slightly garish figures watch you as you sit on a pew. A group of Atacameño children, help tidy up around the church and smile brightly at you when you drop a few pesos in the donation box. Leaving the shade of the church, you pass once more through the modest walls that mark the church boundary. You walk down the street to the tourist office where you join with a handful of foreigners on a minibus into the desert wastes.

Arriving in the Valle de la Muerte (Valley of death) after a bumpy ride through harsh terrain, you abandon your group and head up to the higher plateau that looks out over the reddish sandy valley. Piles of stones seem to have been placed by people to mark the spiritual nature of the place. The Atacameños would have respected the power of the desert here before they were proselytised to Catholicism. The desert around San Pedro is where they once wandered nomadically before settling to farm maize and raise llama. The indigenous religion involved the worship of nature and the taking of hallucinogens. Sitting here, looking out over the imposing desert valley, it is easy to imagine the pre-Christian Atacameño people having visions while beholding the same landscape. Being here is like having a direct link to the past. The Atacameños also were influenced by the Incas in the north and an element of Inti (sun) worship existed in their old beliefs. The sun has decided to hide behind the clouds and distant forks of lightning play across the horizon. Feeling the weather turning, you move swiftly back to your minibus.

After a short drive, you arrive in the Valle de la Luna (Valley of the Moon). The extra-terrestrial landscape that gives the valley its name is stunningly stark. Huge dunes and sand worn rocks make you feel like you are on the surface of the moon. NASA have used it to test out lunar rovers, so similar is the topography to that of the moon. The Atacameños would have felt very much at home in this, their ancestral landscape. Their name in the now extinct Kunza language is the Lickan-Antay, meaning the inhabitants of the land. They linked themselves so strongly to the land and their shared memories of a nomadic past were reflected in their religion before the Spaniards came. Walking through the dunes, you imagine the ancient travellers sitting round a camp fire telling tales and stories from their culture.

Climbing a hill breathlessly in the high altitude, you set yourself down on a rock and watch the sun set over the desert. The sky turns red before swiftly turning black. The clouds obscure some of the sky, but the stars fight to show themselves. Under the astral light and moonshine, you pick your way back down the hill and through the cold desert. Feeling like an early nomad, you trudge through the sands to your waiting minibus. Later, back in San Pedro, you go for a meal in a small cantina. As you dig into your meal, the skies open. Crashing and clanging on the corrugated iron roof above your head is deafening. Sipping a pisco sour, you stay in your refuge as long as you can. Eventually, you bite the bullet and walk out into the streams that were once streets. Wading through the dirt roads, you look forward to your bed, but not to the thin metal roof that shelters it. The desert rains come rarely, but when they do, they are powerful and destructive.

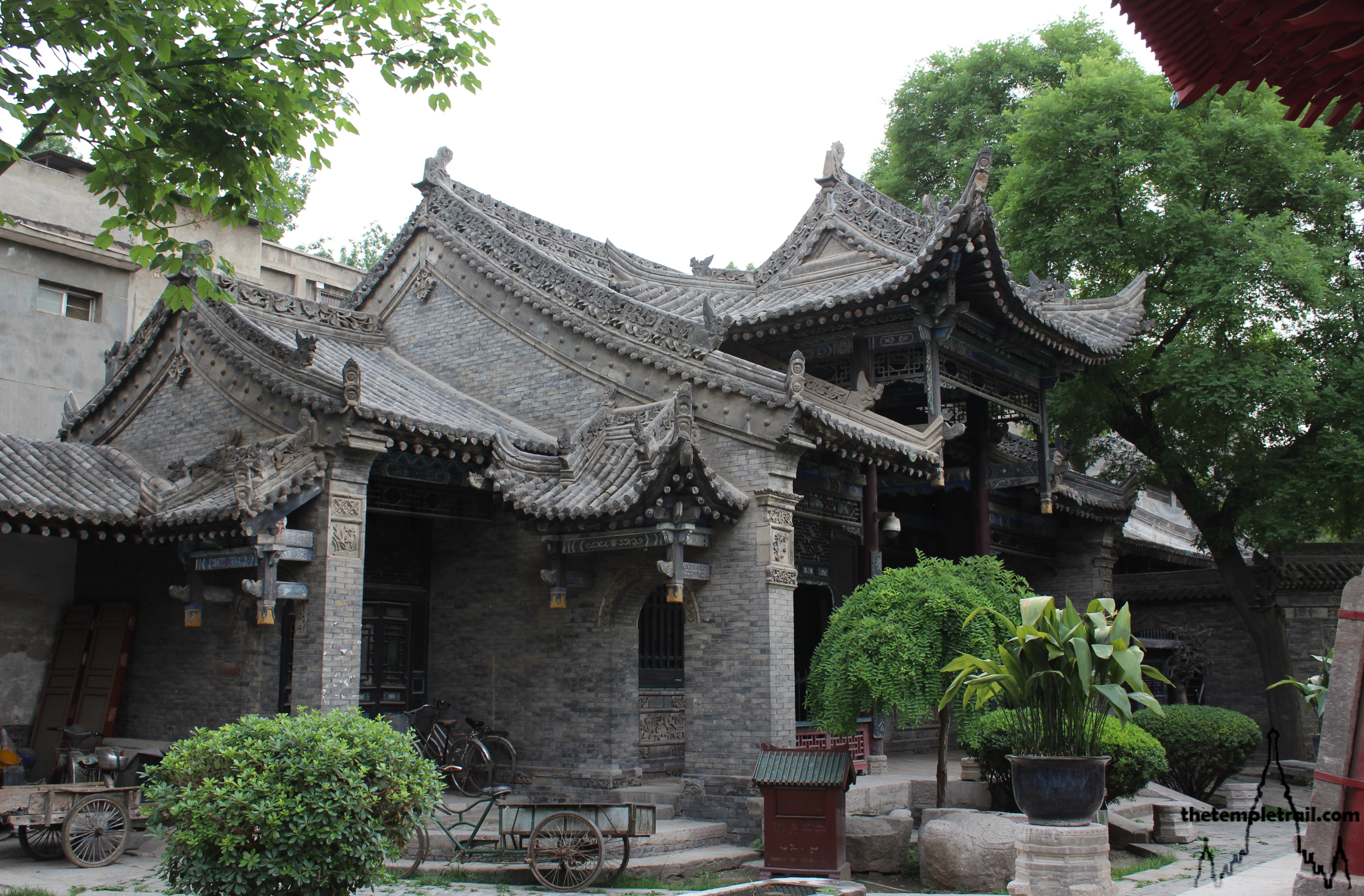

Xi’an Great Mosque

Xi’an Great Mosque