The hired car passes through typical Vietnamese towns as you leave Hoi An and make your way inland. The road starts to climb higher and soon you go past a Catholic church that stands on a hill that was once the home of a much older temple. You continue through the otherwise non-descript town until the foliage begins to get denser. Eventually, the greenery turns to forest and the terrain gets steeper. The jungle continues to get thicker until you arrive at the ticket office and museum. After buying your tickets, the driver takes you a little further down the jungle road and abruptly stops. You will have to go the rest of the way by foot. He waves you down the road in a very noncommittal way and then gestures more vehemently when you question him further about the directions he has given.

Slogging down the jungle road for a kilometre or so brings you to the entrance of the site. The views are unbelievably beautiful. On the way to the entrance you pass through ancient forest and a body of water. The heat is oppressive and the sound of tropical birds and the chirping of insects is the soundtrack to your rigorous, yet rewarding walk. As you enter the compound, there is no one to greet you. You have the place to yourself. The jungle reclaimed so much of this place. Bored American teenagers bombed it heavily as a malicious act of disdain during the Vietnam War, yet it is still here to tell its story to anyone who wishes to see it. It was once the holiest place in the Kingdom of Champa in what is now central Vietnam: Mỹ Sơn, the temples and burial sites of the Cham kings.

Mỹ Sơn was continuously used from the 4th until the 14th century AD. What you see today dates mainly from its heyday in the 10th century and is mostly in the Mỹ Sơn A1 style. The temples were built to honour Shiva (Bhadresvara in the local language) and the number of lingam (phalluses) on the site attest to this. Mỹ Sơn eventually fell into disuse due to territorial losses to the Khmers and, ultimately, the Dai Viet before it was finally swallowed by the jungle.

In the 19th century, the French archaeologist, Henri Parmentier, worked extensively on the Cham sites around what was then French Indochina, particularly Mỹ Sơn which he rediscovered in 1898. In the late 1930s, the temples at Mỹ Sơn were reconstructed and they remained in that state until the late 1960s, when the area was carpet bombed by the Americans. Huge areas of the forest are still inaccessible due to unexploded devices.

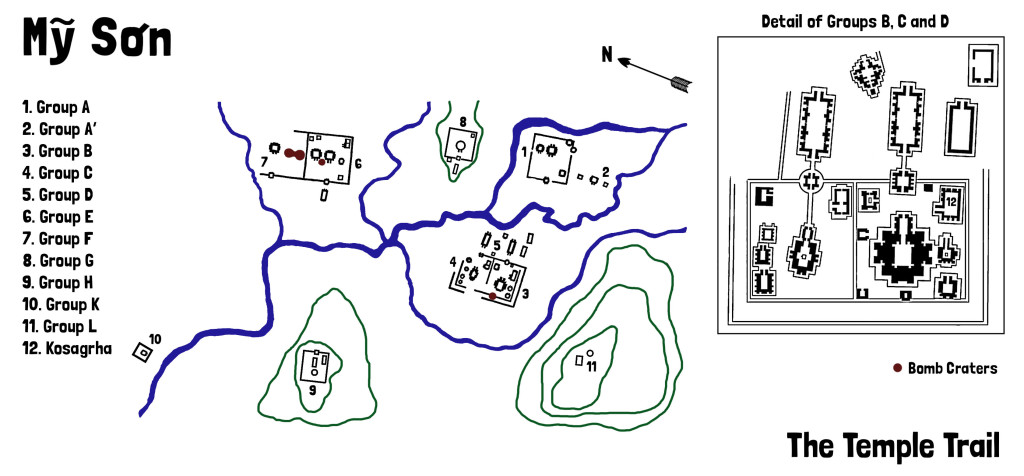

Stepping into the picturesque site of the largely unheard of Champa Kingdom is like intruding on a sleeping creature. You feel that at any minute the whole place could come alive; but it stays dormant and you are free to explore its hidden gems. Upon entering, the first temples you see are those of Groups C, D and B. The brick structures are a little overgrown, yet the beautiful Cham relief work shines through. The buildings are made of red brick and the techniques used to build them are not fully understood. The bricks are almost seamlessly put together and there is no visible mortar. The most likely theory is that the buildings were built using unfired brick and mortar of the same materials and then fired as fully standing buildings. The reliefs are carved directly into the bricks, a distinctly Cham method, enhancing the oneness of the structures.

The first groups are in the best condition and you can see different varieties of buildings here. Group B is particularly wonderful. Here you see the superb B5, also known as the warehouse. This building, with its distinct saddle shaped roof is a kosagrha or firehouse. These types of buildings were used to store the chattels of the deity and also served as a kitchen in which to cook food for the gods. The building is one of the most complete on the site and is certainly the most iconic remaining one.

There are also the remnants of three kalans; brick sanctuary towers. These feature intricate carvings of deities and other figures. Cham towers are very similar to Khmer towers. A kalan, much like a Khmer prasat, features a mandapa (porch entrance) and a tall intricate spired roof. They both have highly decorative carved tympana (half-moon shaped reliefs over the doorway) and if you did not know that you were in Vietnam, you could be forgiven for thinking you were in Cambodia.

After wandering around this group admiring the architecture, headless statues and the huge stone lingam next to B4, you exit through the ruined gopura (gateway) and through Group D to the bridge over the river. Here you take a moment to gather your thoughts and take in your surroundings. All around you is thick jungle and a dirt path lies in front of you leading you towards Group A. The rushing of the water has a calming effect and it is not difficult to see why this area was deemed sacred by the ancient Cham.

Taking the right fork of the path, you get to Group A. This was once home to one of the largest and most impressive temples in the complex: A1. It survived sustained carpet bombing, until one day an American bomber decided to dump its load directly on the building that reduced the once magnificent temple to a pile of rubble. A building that had stood for a thousand years was wiped out in a matter of seconds. The outline of A1 still remains and the carved pedestal that once held the enormous lingam and yoni is very impressive.

Standing in the middle of the temple, you are overwhelmed with sadness. The destruction of the temple is a stark reminder of the destruction of war and the terrible human cost on both sides. Here, in this once fabulous place, you see that there is never a true victor. Leaving the overgrown remains behind, you travel back up the path and past the out-of-bounds Group G, that is closed for reconstruction. Eventually, Group G will be a stunning reconstruction on the hill on which it sits.

Following the path, you came to Group E and F. The front of Group E has a large number of sculptures, including a spectacularly well preserved segmented jaṭāliṅga. The Cham, being Shaivites (worshipers of Shiva) at that time, revered the lingam. They had two main varieties: the jaṭāliṅga and the mukhaliṅga. A jaṭāliṅga features a carving of Shiva’s chignon hairstyle and a mukhaliṅga has an image of the god’s face or whole body on it. They can be segmented into three layers: a square base, octagonal centre, and circular top, representing the trimurthi of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Going past two fairly ruined towers, you get to the back of the site and the tower that is called F1. It is mostly rubble and is propped up by supports. The staircase of this tower is wonderful. You can’t climb it, but you can see how fantastic the tower would have been in its prime.

Exiting the site via the tree lined pathway along the river, a sense of happiness walks with you. The site may have taken a few knocks, but it is still here and will continue to be with a little help from the Vietnamese. The people working on the reconstruction of the site are mainly locals, many of them Cham people. They have been assimilated into Vietnamese society, but a lot of the Cham still maintain their distinct culture. Some still worship gods in the towers scattered all over this part of the country, but most Cham are now Muslim and have been so since before their kingdom fell. Regardless of whether they share the same religion, there is something fitting about them working on the temples constructed by their ancestors more than a thousand years ago.

Wat Phrathat Doi Suthep

Wat Phrathat Doi Suthep