The dry summer heat of Beijing is sapping. Walking on hard surfaces of the concrete streets is a bone-pounding, strength stripping feat. The modern city is not designed to be traversed on foot and after a few hours, you are feeling the effects. Thankfully, a shaded pavement area east of the Forbidden City gives you a short interval to recharge your stamina. You pass the ancient Guǎngjì Sì (廣濟寺), a temple that is both old and popular. Inside, a festival is in full effect and devout revellers, pray and chatter to each other in happy rapture. You enter the front gate of the temple to take in the Ming rebuild of the Jin Dynasty temple. The vibrant activity buoys your spirits and rejuvenates you. Stepping back out of the gate, you head to the next temple on the street. This is no ordinary temple. It is a unique building in Beijing and China. Within a few metres, you terminate your walk at Lìdài Dìwáng Miào (歷代帝王廟); the Imperial Temple of Past Emperors.

Also known as the Temple of the Emperors or the Temple of Ancient Monarchs, this set of structures that was once hugely neglected, has been restored by the government in order to reclaim Chinese history and establish a more tangible line of rule back through the ages. After being used as a school in the 1930s, semi-demolished during the Cultural Revolution and maligned by the Communist Party, the structures now fulfil the purpose they were created for. In the mid-90s, the once detested temple, rose once more to some semblance of its former glory. In 2004, after a 36 million dollar makeover, the temple was opened to the public for the first time in its history.

Originally, it was constructed in 1530 during the reign of the Ming Emperor Jiajing (嘉靖 Jiājìng) as a twin of the temple built by the first Ming Emperor, Hongwu (洪武帝 Hóngwǔdì) in Nanjing in the 14th century. The Jiājìng Emperor was a cruel and neglectful ruler, who chose to ignore the needs of the state in order to live in relative seclusion outside of the Forbidden City. He was obsessed with finding the Elixir of Life and sexual magic with scores of young teenage concubines. He favoured ruthless and violent punishments to those who defied him and employed the ‘death by a thousand cuts’ (凌遲 língchí) form of execution. His long and vicious reign was ended after 45 years when he died from mercury poisoning, an ill effect of a potion believed to be the Elixir. His legacy includes the building of the Altars of the Earth, the Moon and the Sun. He also expanded the Temple of Heaven. As a proponent of Taoism, he actively persecuted the Buddhists and the gateway you stand at now, once led to a Buddhist temple called Bao’an Sì. The Emperor chose the site as the location for his Lìdài Dìwáng Miào as part of his suppression of Buddhism. His religious zeal, financial mismanagement and lack of leadership paved the way for the loss of the Mandate of Heaven and the end of the Ming Dynasty less than a hundred years after his death.

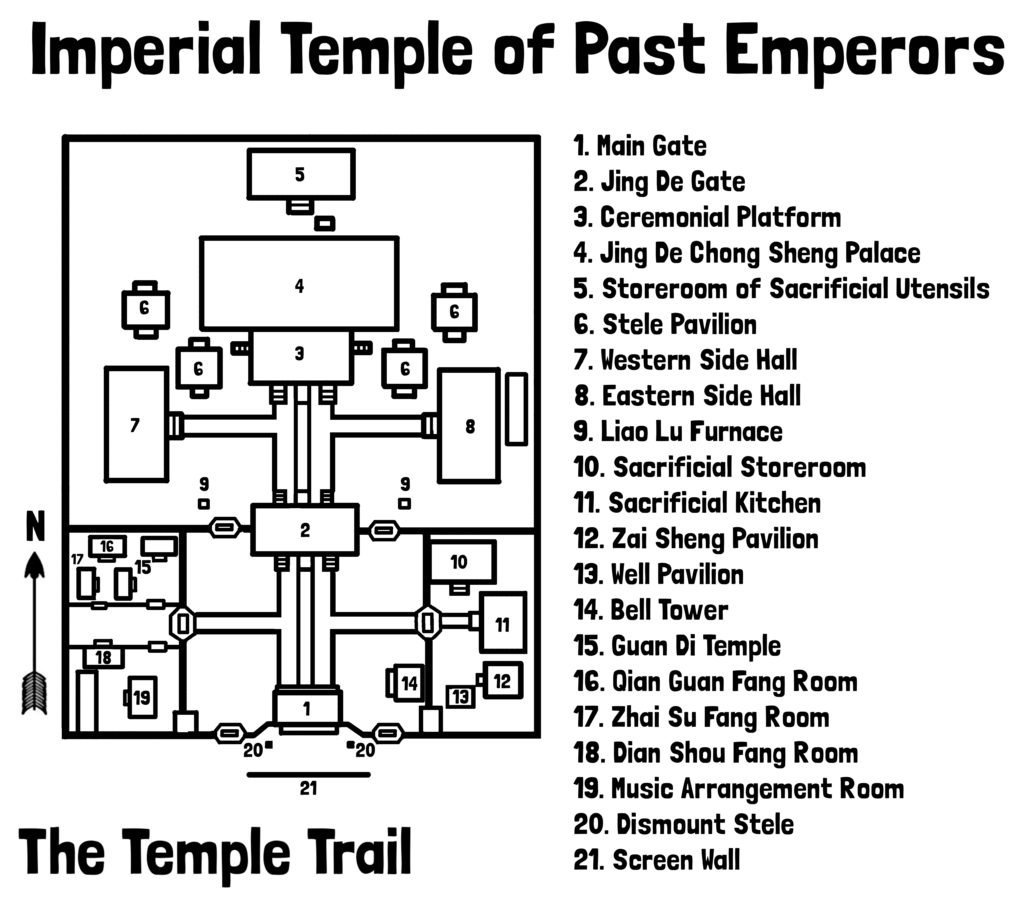

Worship ceased upon the fall of the Qing Dynasty and sacrifices were made in the spring and autumn. Emperors often sent representatives in their stead, although some went more than others in person. Originally, the entrance had three marble bridges and a wonderful wooden ceremonial arch (牌坊 páifāng), but these features were sadly torn down in the mid-1950s as feudal relics. Next to the main gate is a stele, originally one of a pair, that tells you to dismount. As you are not riding a horse, you see fit to enter the compound. Opposite the gate is the screen wall (影壁 yǐngbì) of the temple that stopped evil and malicious spirits entering, as you are now doing.

The small first courtyard is a lobby of sorts. It contains a bell tower to your right, but little else. There are three ways to proceed from where you stand. To your left is a gateway that leads to the Guan Di Temple and other halls. The Guan Di temple (關帝廟 Guān Dì Miào) was built during the Qing Dynasty to worship Guān Dì (關帝), the ancient Chinese general Guān Yǔ (關羽) in his deified form. The temple acts as a museum these days and is filled with an exhibit on the Three Kingdoms Period general. To your right lies a more interesting set of buildings. Through another gateway, the Rebirth Pavilion (再生亭 Zài Shēng Tíng), Well Pavilion (井亭 Jǐng Tíng) and Sacrificial Storeroom (神庫 Shén Kù) all had functional purposes and centre around the main building in the area; the Sacrificial Kitchen. This building, which now also houses an exhibit, was used to make sacrificial animal offerings. Originally built in 1530, it is a relatively small structure at three rooms wide and one room deep (a room is a Chinese unit of measurement. One room is approximately 5.5 metres. There is in fact no physical division of the space inside the chamber). The roof is a flush gable roof (硬山 yìngshān), one of the simplest in the whole complex.

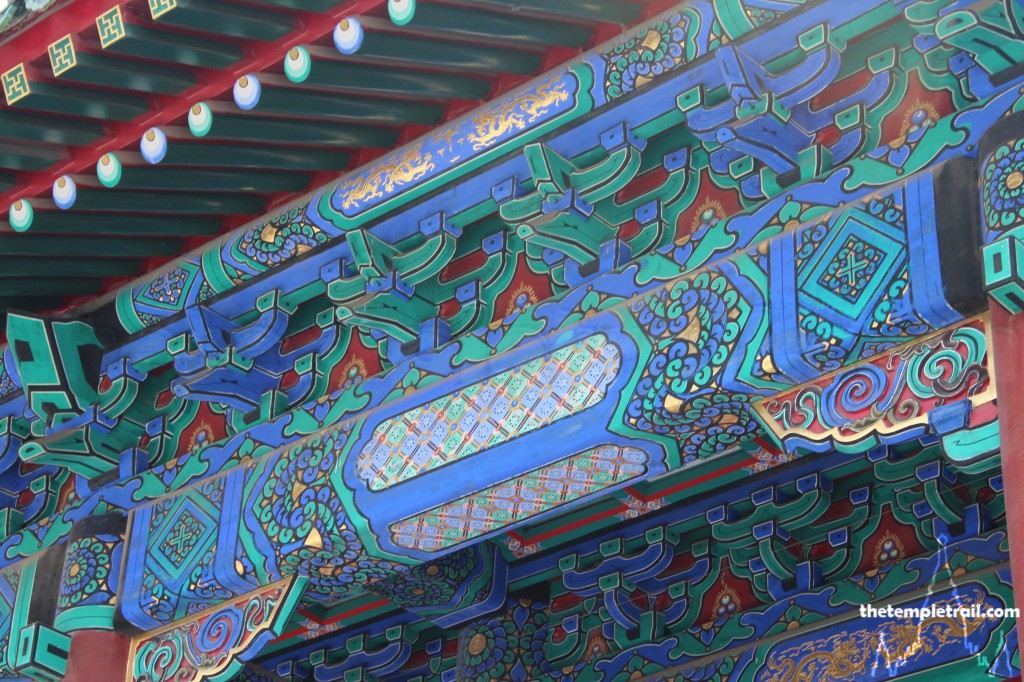

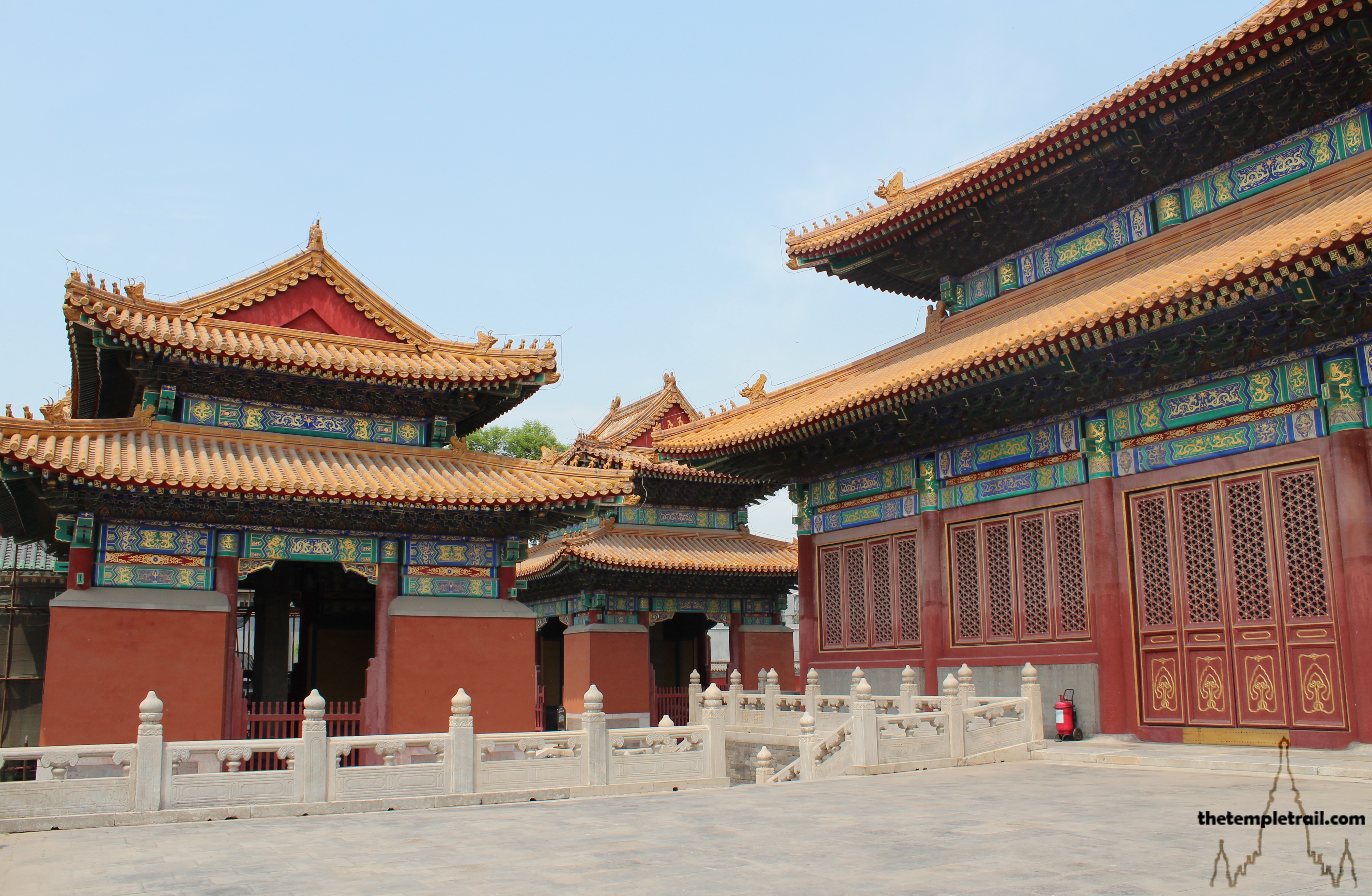

Back in the first court, you enter the Jing De Gate (景德門 Jǐng Dé Mén). This, the second large gate of the temple grounds, has been semi-restored and the ceiling partially repainted. It is a testament to the advances in restoration and curation in China that the authorities left some of the ceiling as it was. The gate leads into the main courtyard. The vast open space is dominated by the Jing De Chong Sheng Palace (景德崇聖殿 Jǐng Dé Chóng Shèng Diàn); the main hall of worship. Lining either side of the courtyard are the West Minor Hall (西配殿 Xī Pèi Diàn) and the East Minor Hall (東配殿 Dōng Pèi Diàn). These two long, thin buildings hold the worship tablets of 79 eminent generals and ministers from all of the imperial rules. The West Minor Hall holds 39 tablets and the East 40. Both have a double-gabled “gable and hip” roof (歇山 Xiēshān) and are seven by one rooms in dimension. They were originally built in 1530, but reconstructed in 2004. Two furnaces are either side of you at the gateway. The West Liao Lu Furnace (西燎爐 Xī Liáo Lú) was used to burn paper and silk offerings for the ministers and generals in the two halls. Across from the white furnace is its sister; the East Liao Lu Furnace (東燎爐 Dōng Liáo Lú). It is exactly the same, but is green-glazed. The glinting structure was used for the ritual burning of items for the emperors contained in the main hall.

You walk down the centre of the courtyard and in front of you four stele pavilions frame the Jing De Chong Shen Palace. They contain huge stone turtles that carry tall stelae on their backs. The two southernmost are the most interesting. The southeast pavilion was built in the 50th year of the Yongzheng period (雍正Yōngzhèng) of the Qing Dynasty (1733). With its double gabled xieshan roof and floor engraved with cliffs and sea patterns, it is elaborately beautiful. The seven and a half metre-tall stele is unique. One side is in Manchu and Chinese, and dates from 1733. The other side was engraved in 1785 during the Qianlong period (乾隆 Qiánlóng). The fact that it was carved on the instructions of two successive emperors has led it to be called the Father and Son Stele. The diligent and hardworking Yongzheng Emperor (雍正帝 Yōngzhèng Dì) came five times in his 13-year reign. Perhaps, as he usurped the throne by killing his brother, he wished to atone. His despotic and vigorous rule was an era of peace and saw a crack-down on corruption and the formation of the highly influential Grand Council.

The southwest pavilion was built in the 29th year of the Qianlong period of the Qing Dynasty (1764) and contains a six-metre-high stele. The reign of the Qianlong Emperor (乾隆帝 Qiánlóng Dì) is known for its length and Frontier Wars, both successful and unsuccessful; in the case of the war in Vietnam, embarrassingly so. The empire almost doubled in size during his rule. Despite being an art lover, he was known also for book-burning and re-editing other works. He executed more than fifty writers and academics by beheading and língchí slow slicing. His reign that started out strongly with expansion ended with the beginning of the decline of the Qing dynasty. When he abdicated in 1796 after nearly 61 years on the throne, the Western and European powers were already making moves into China.

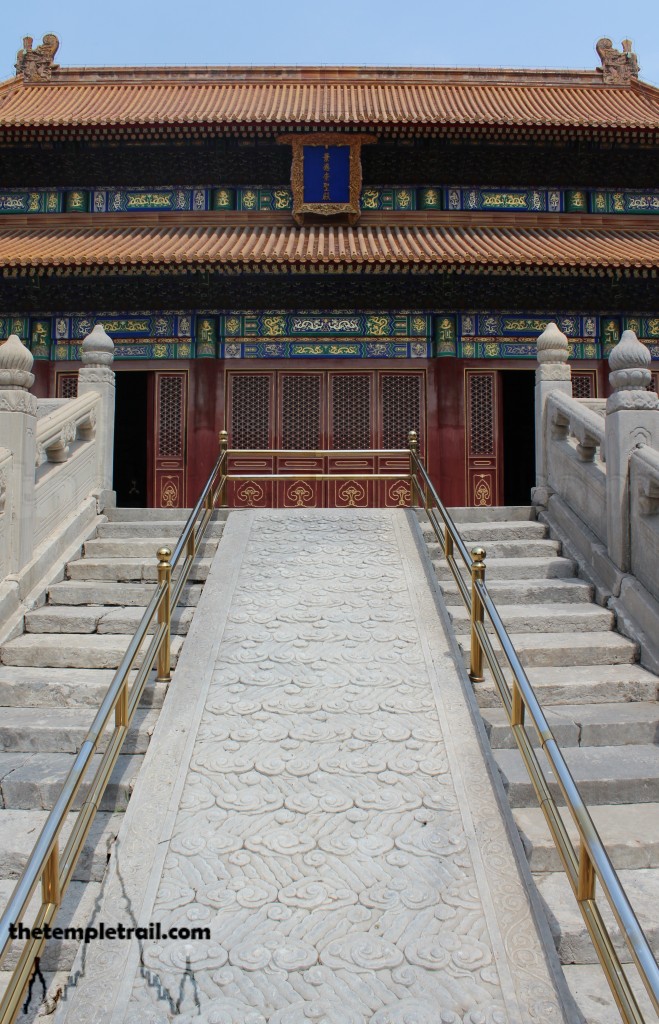

You enter the Jing De Chong Shen Palace and in front of you an array of tablets fill the back of the room. The red plaques are stacked inside dragon carved golden altar cabinets. By the time of the Qianlong Emperor, 188 historical emperors had ruled China. The tablets you see are these emperors. Originally built by Jiajing, it was rebuilt by Yongzheng and Qianlong. Its double-eaved, yellow-tiled roof is spectacular, but inside, the spun gold artwork, Chinese cedar (楠木 nán mù) wood columns and smooth paved floor make it the epitome of imperial construction. The large hall is nine rooms wide, by five rooms deep (51 by 27 metres). The focus of worship here is the Three Sovereigns ( 三皇 Sānhuáng) or Three August Ones. These three are the semi-mythical, historical founding rulers of China. The three divine kings are the heart of Chinese ancestor worship and all three are the founders of Chinese society. All three ruled in the third millennium BCE and are considered to be wise god-kings.

The first is Fúxī (伏羲). Fúxī came from an unknown place called Chengji in either Shaanxi or Gansu province. He was historically a chieftain of the earliest eastern tribes in China in the mid-29th century BCE. He is said to have taught the people fishing, hunting and animal husbandry. He is also credited with the Creation of the eight trigrams (八卦 bāguà). He is seen as the earliest ancestor of Chinese people. According to legend, he and his sister Nǚwā (女媧), with the blessing of the Emperor of Heaven, procreated the human race after a great flood. They also created many people from clay and brought them to life. The pair are often depicted with serpent tails intertwined.

The second is the Flame Emperor (炎帝 Yán Dì), better known as Shénnóng (神農). Shénnóng was a chieftain of the tribes of the Jiang River region. He moved east along the Wei and Yellow Rivers into central China, where he gained fame. He is the inventor of the lěi sì (spade-shaped plough), who taught the people farming. Shénnóng means “divine farmer”, and it is in this role that he is most revered. Sometimes, he is referred to as ox-headed or sharp-horned, and is occasionally depicted with horns. Cattle cannot, therefore, be sacrificed to him. Instead, pigs and sheep are used to appease him. He also taught the use of medicinal plants, and is worshipped as the King of Medicine (药王 Yào Wáng). The myths say that he died trying herbs on himself and he sacrificed himself for mankind about 5000 years ago. He also has his own temple in Beijing, the Altar of Agriculture (先農壇 Xiān Nóng Tán), where the emperors would pray for a good harvest.

The last of the three is the Yellow Emperor (黃帝 Huángdì). His given name was Xuānyuán (軒轅) and he was born on Longevity Hill (壽丘 Shòu Qiū) in Shandong province. He is credited with Creating sericulture (raising silkworms), vehicles for transportation, the written characters of Oracle Bone Script, music, the instrument called the gǔqín (古琴), medicine (along with Shénnóng), and arithmetic. He is seen as the father of human culture. Historically, he ruled in the 27th century BCE. His mythology involves the defeat and submission of various beasts, demons and supernatural creatures. Apart from the Three Sovereigns, the Five Emperors (五帝 Wǔdì) are also represented. The Five Ancient Emperors, all descendants of the Yellow Emperor, are Shǎohào (少昊), Zhuānxū (顓頊), Kù (嚳), Yáo (堯) and Shùn (舜).

The vast space seems empty, despite the presence of so many former emperors. Walking out to the veranda, you circle the building and look at the small Storeroom of the Sacrificial Utensils (祭器庫 Jì Qì Kù). It was used to store the requisite items needed for sacrifices to the emperors. After completing your circle, you retrace your steps to the front of the temple complex.

Going down the road, you see the locked up Miàoyìng Sì (妙應寺), also known as Báitǎ Sì (白塔寺) with its famous Yuan Dynasty dagoba (stupa). The temple is being renovated in the same way that the Temple of Past Emperors has been. The reversal of the damage done during the Cultural Revolution and other ideological crusades is now in full effect in Beijing. The resurrection of old China, with a modern political twist, is inevitable; it’s just a matter of time.

Tin Hau Temple Complex

Tin Hau Temple Complex