The dusty streets of Kashgar’s old town provide you with many sights. Walking through the streets, covered in a patina of powder, you watch copper craftsmen beating bowls out by hand. Everywhere, the smell of lamb over coals permeates the air. Bread sits out on tables in the street enticing you with its just out of the oven aroma. Stopping at a stand, you buy a small cup of Turkish ice cream from one of the ethnic Turks who has settled in this Uyghur town. The city in far west China is the most remote in the Middle Kingdom. The Central Asian atmosphere is heightened as you pass rug shops and tea houses filled with Uyghur men in their distinctive hats. The sound of their songs echoes out over the streets.

Sadly, much of the old town has been rebuilt to look more like a Disney version of what it once was. The Chinese government, in an effort to attract tourism, has been renovating the area heavily. A few old mud-brick Uyghur houses remain and the sights and sounds help retain the culture of the town. Turning a corner, you come to a large open square in the middle of the old city. A truly original and time-tested building stands proudly over the ancient settlement. Built in 1442, the Id Kah Mosque is an iconic part of Kashgar and the entire Xinjiang region from which 100,000 devotees travel each year to pray during Eid.

Known as the Hëytgah Meschiti (ھېيتگاھ مەسچىتى) in Uyghur and the Àitígǎěr Qīngzhēnsì (艾提尕尔清真寺) in Mandarin, the mosque takes its name from the Persian word Eidgāh, meaning place of festivities. Built by Saqsiz Mirza, the ruler at the time, in 1442 AD on a 10th century mosque site, the Id Kah Mosque is the largest in China, holding up to 20,000 people. The original mosque was built during the golden age of Kashgar, when it was one of the capitals of the Kara-Khanid Khanate between the 10th and 13th centuries. The mosque was destroyed when Kashgar was sacked by the famed Turco-Mongol conqueror Amir Timur (Tamerlane) in the 14th century. The city at that time had been mixed in terms of religion with Buddhists, Muslims and Nestorian Christians calling it home. By the time of Saqsiz Mirza, the Nestorians had disappeared and the town was a fully Muslim settlement. The mosque was expanded in 1538 by Ubul Abidek and then restored and renovated several times in the 18th and 19th century.

Standing before the magnificent façade, you cast your gaze over its Central Asian styled entry arch. The yellow glaze of the tiles reflects the bright rays of the Xinjiang sun. The main arch sits between two tall minarets, one directly next to it and one spaced apart by two false arches. The towers are decorated with bands of blue and green tiles that highlight the yellow ones. Topped with crescent moons, they show the faithful where to come for prayer. The main portal is square, but echoes the arch motif that is found in the two to the left. Around it, 15 miniature arches decorate the façade of the great door. Approaching the door, you pass many Uyghurs who have been praying inside the mosque.

At the front, you look up and trace the lines of the detailed calligraphic plaque that hangs above the door. The bright colours of the painted lines stand out from the plain background of the yellow tiles. Your eye is drawn to the thin band of intricate tiles that follows the inner line of the arch above the square doorway. From this bright exterior, you step through the doorway, past the great copper lined doors, and into the shady entrance hall under the dome of the gateway. The space is immediately calming. Uyghur men rest in the cool interior of the gate building and eye you as you pass through it and out to the open area of the huge mosque.

You find yourself on a tree lined pathway that is fully shaded from the blazing sun. In this quiet area, so sheltered from the dust and noise of Kashgar, you find it hard to believe that so much violence has happened over the history of the mosque.

After a short-lived independent East Turkestan, Kuomintang-allied forces moved in on Kashgar and retook it in a violent attack that saw the British and Russian Embassies in Kashgar sacked. The Chinese Hui Muslim General Mǎ Zhàncāng (馬占倉), who served the Ma Warlords, had Timur Beg, the Uyghur leader shot and beheaded and his head displayed on a spike in the mosque in 1933. A year later in 1934, he displayed the head of Emir Abdullah Bughra in the same manner. A month after the violence, the higher ranked Hui warlord, General Mǎ Zhòngyīng (馬仲英) gave a speech at the mosque and instructed the Uyghurs to swear loyalty to the Republic of China and the Kuomintang. The most recent case of political violence happened in 2014, when the Communist government appointed Imam of Id Kah Mosque, Jume Tahir, was stabbed to death by local assailants who were displeased with his pro-Beijing sermons.

In the now tranquil grounds, you walk up the path towards the prayer hall. To your left, you see a courtyard that acts as a rest area and an overspill for very busy prayer times. The front of it has a roofed area with carpets on the ground for devotees to pray side by side on. Continuing further, you find two more of these overspill courtyards. Uyghurs rest and even sleep on benches in the cool shade. In the centre of both of these areas is a small tower with steps. On top of them are loudspeakers so those who could not get into the prayer hall can hear the prayers and sermons of the Imam. At the end of the path, after walking through the large open space of the centre of the mosque, you come to an open gate. Quranic verses are displayed on both gate posts which are made of yellow painted brick to match the front of the mosque. Passing through, you stand before a set of steps that lead up to the main prayer hall.

You climb the steps and before you lies a roofed open area with carpeted floor. In front of it is a mezzanine platform with carpets laid out for prayer. Passing these, you climb another set of stairs and stand on the floor level of the hall. Removing your shoes, you walk on the carpet towards a side door and plunge into the darkened interior of the hall.

Rows of green columns line the white hall. Green prayer rugs cover the floor. A small group of men with white cloths wrapped around their heads sit at the front of the hall rapt in prayer before the Qibla wall. The direction of Mecca is indicated by the miḥrāb, a niche that acts as an arrow. The large one here also contains the mimbar, a high chair from which the khatib (sermon giver) talks to the congregation during Jumu’ah (Friday Prayer). At Id Kah Mosque, this is done by the Imam, as the Chinese government selects the leader of its congregation, so as to ensure no dissent among the Uyghur majority of Kashgar.

After a few moments in the simple hall, you step outside again and put your shoes on once more. The green carpets cover the roofed area outside the hall also, allowing thousands of faithful to pray together during the five daily prayers. Under an incredibly ornate roof section, an equally adorned window marks the spot of the miḥrāb inside. Intricate patterns surround the miḥrāb window, including floral motifs and geometric designs incorporating swastikas, perhaps a throwback to the Buddhist heritage of the Uyghurs. The Uyghurs have converted a number of times. Originally Shamanists, they converted to Manichaeism, then Buddhism and, finally, Islam. The square pattern on the roof is offset from the centre and the miḥrāb window sits on the left side of it. The designs are mimicked and made even more intricate on the panel and the floral theme is expanded upon in detail.

Walking away from the decoration on the otherwise plain structure, you make your way back through the compound. The peaceful nature of the mosque belies its violent history and walking back, you reflect on how the situation is still mercurial at best. The mosque is a symbol of the Uyghur people and central to the East Turkestan state movement. It is for this reason that the Chinese government keep such a tight rein on it. By controlling the mosque, they believe that they have control over the people. How long this will continue, only time will tell. In the meantime, you appreciate the green oasis in the desert of the city and hope that there are no more violent days in the future of Id Kah Mosque. From the tranquil shady spot, you exit back out into the blistering heat of Kashgar and its exotic scents and sounds.

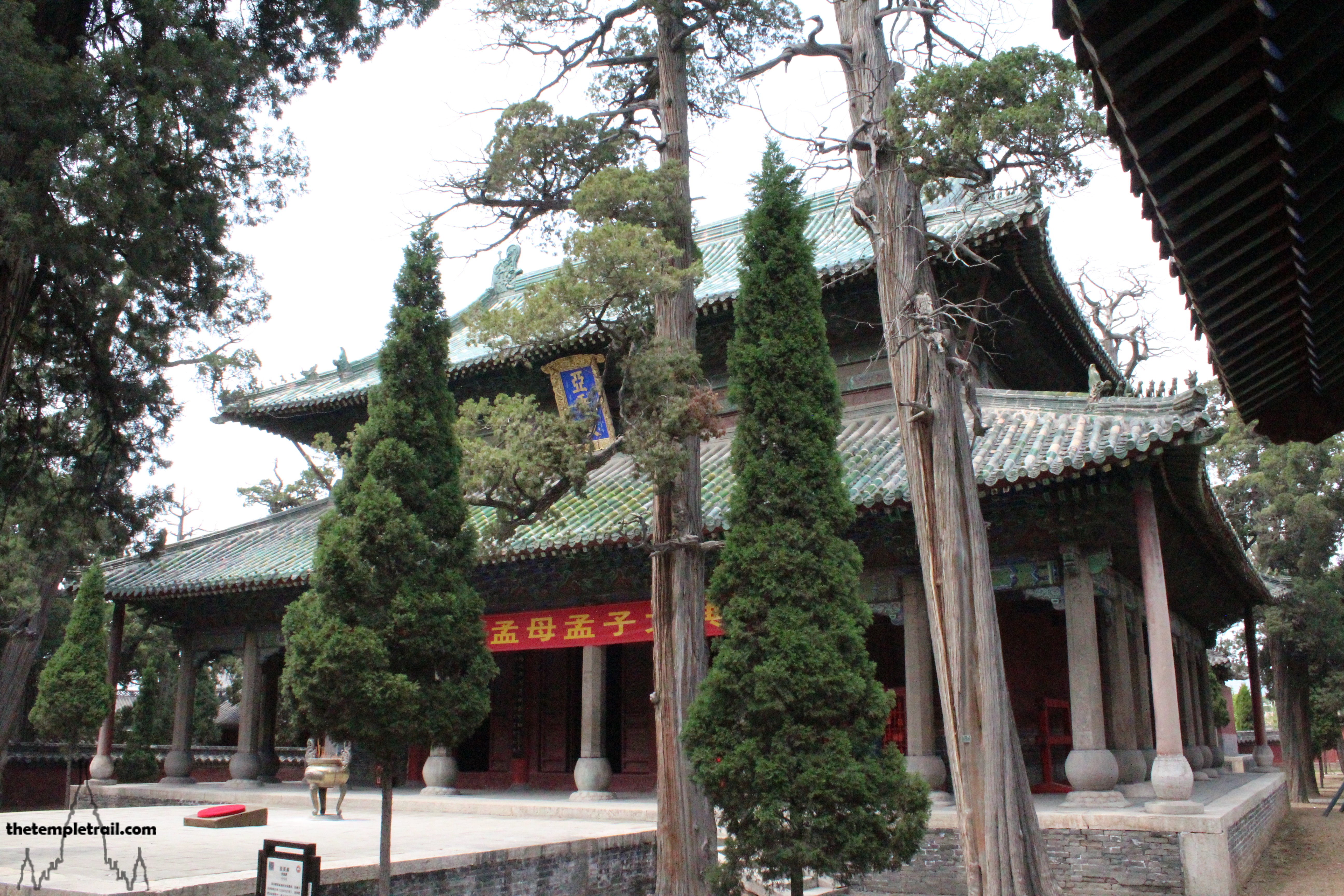

Mèng Miào

Mèng Miào