After enjoying your lunch of ceviche and papas huancainas, you leave the small hole-in-the-wall restaurant. The acidic, spicy fish was balanced with the creamy piquant potatoes and you stroll out into the streets of Lima to aid your digestion. Your post-prandial perambulation takes you past modern apartment buildings that are evidence of Lima’s rising economic trajectory. The Peruvians are upwardly mobile and they want the luxuries that go with the territory. As you cut down small alleyways and past corner shops, the modernity of the city is hard to ignore. Security guards sit in booths at the electronic gates to exclusive condos and in front of businesses selling luxury goods. The Lima of the past is hard to find in this part of the city; Miraflores is really the jewel in the crown of contemporary Lima. Rounding a corner, you are smacked in the face by an enormous relic from ancient times. A huge adobe pyramid constructed by the Lima Culture in the early first millennia AD still dominates the spot it was built on so long ago. Huaca Pucllana (the place of ritual games) looks totally out of place mingled with the modern Peruvian architecture.

Huaca Pucllana (or Huaca Juliana) was significant as both a ritual and administrative centre. The priests led the religious rites and governed the community. It was the epicenter of the Lima Culture that ruled in the Lima area and over the Chancay, Chillón, Rímac and Lurín valleys from the 3rd until the 8th century AD. Huaca Pucllana was the touchstone that ignited and then led the cultural growth of the area prior to the dominance of the Huari (Wari) culture that eventually replaced it.

The site originally had a number of smaller pyramids and plazas that grew as each generation added to it. The administrative area was made up of a number of patios, platforms and storage facilities. The agriculture and food management of the area was the primary concern of the governing body of holy bureaucrats and the administration of these affairs would have taken part in the more secular part of the site. Agriculture and food supply would have been religiously significant. The worship of ancestors and the gods was inscrutably linked to the success or failure of the crops and the bounty of the sea. Taxation of farmers and fishermen occurred here and the commodities they provided were part of the ritual offerings given at the great pyramid. The importance of the sea to the Lima Culture is abundantly apparent through the artwork on the ceramics recovered at the site. Marine motifs were the dominant decorations and imagery of various sea creatures can be found on most of the pottery.

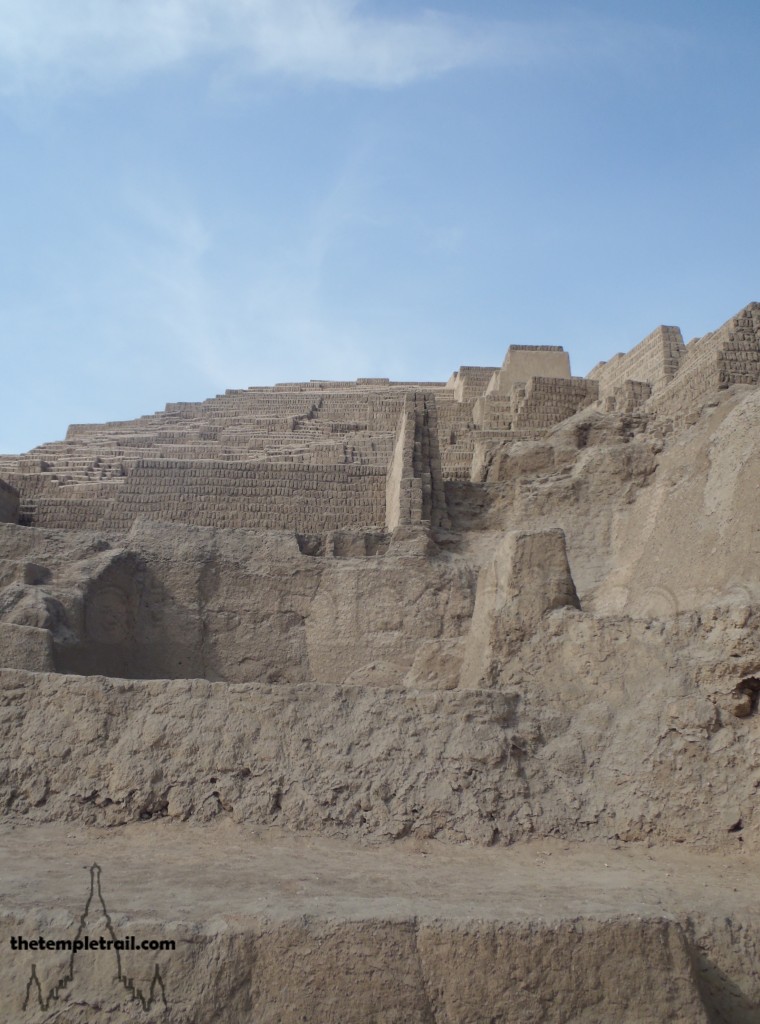

Venturing into the enclosure, your view is fully imposed upon by the massive adobe huaca (pyramid). The huge mud brick structure is more than 500 metres long, 100 wide and 22 tall. The adobe bricks are staked on end with a horizontal layer on top of each row. As the sun highlights the strata, it appears to your eye as if you are in an enormous outdoor library. The bookshelf technique is a trademark of Huaca Pucllana and the eight meter tall trapezoidal wall sections are really standout. It’s a monster of a construction and it not only dominates the space it occupies today, but would have been visible from miles around when it was constructed. The ancient people of the region would originally have worshipped mountains and large rocks (these were also called huacas) and the large pyramids were very much an attempt to emulate them. Zig-zagging ramps take you through the complex structure that evolved over hundreds of years. Originally plastered, the huaca was painted yellow, which seems to have been a ritually important colour for the Lima people. The priests would have gathered on this man-made mountain to give offerings to the gods of the elements and to generations gone. The ceremonies involved human sacrifice and the ritual smashing of large decorative pots followed by feasting. The remains of young women in the proximity of ceramic shards are a testament to this. The ramps and passages have yielded food remnants that suggest banqueting on high status items such as shark flesh.

The discovery of stone tools, textiles and ceramics shows that a complex social group developed here and that these goods were revered by the Lima people. Their society, much like that of the present day Limeños, revolved around food. The remains of many food animals (fish, guinea pigs, molluscs, deer and ducks) have been found. The Lima people were not only skilled fishermen and hunters, but also accomplished farmers. Their agricultural exploits can be seen from the remains found at Huaca Pucllana; lima beans, corn, squash, lúcuma, cherimoya, guava and pacay. The rich pastoral heritage laid the foundations for the bio-diverse food culture that you have been enjoying for the last few days.

Irrigation channels once divided farm land and the Lima people’s reed houses would have surrounded the huge adobe pyramid that towered above the low-lying landscape. Your route takes you around the huaca in the shadow of which the early Lima people made textiles of alpaca and vicuña wool, wove baskets, made pottery, worked the plantations and hunted. The sun lights up the uneven surface of the edifice. The smooth sections that have been eroded from more than a millennium of exposure to the garúa (dense coastal fog of Lima) contrast sharply with the restored sections and their jagged edges. As the shadows play on the recesses of the pyramid, it’s easy to imagine the scene 1500 years ago: the sun beating down on the raised platform as the priests gave offerings to the gods; below them the people going about their daily lives and the blue ocean glittering under the burning sun.

Standing on top of the great pyramid, you can feel how it was used as a place to control the local population. You can see how the priests were able to use their status to wield influence. A few members of the social elite (perhaps the warrior elite) from the Lima Culture were also buried here. This reinforced the power of the pyramid and its link to the ancestors. It was an imposing reminder of where the power lay and who ratified that power.

The Lima Culture came crashing down with the arrival of the Huari in 700AD. They overthrew all of the cultures of coastal Peru and became the dominant force in the region. Huaca Pucllana was mostly abandoned, but the Huari used it as a political tool. They destroyed the top layers of the pyramid and interred their own nobility there, turning it into a graveyard of their own elite. This effectively raised their own ancestors above those of the native Lima people. By 800AD, the Huari Empire collapsed and the Ichma people from Pachacámac desecrated the Huari graves and used the site for sacrifices to their god Pacha Kamaq (Creator of the World). The Ichma were absorbed by the later Inca Empire and when the Incas arrived in Lima, Huaca Pucllana was already known as a ñaupallaqta (sacred ancient village).

Leaving the site that was ancient in the time of the Incas, you can’t help but marvel at the power that the pyramid held over the Lima of one and a half millennia ago. The energy from the site is astounding. It radiates authority over the surrounding area to this day and the culture that was born under its shadow still resonates through the streets of the city. The bounty of the sea and the land are still sacred to the Limeños and the undeniable influence of Huaca Pucllana can still be felt, even if it is no longer the tallest structure in Lima. Looking at it from ground level, you see that it still has the ability to awe and inspire. It is as much a part of the landscape, both culturally and physically, as the sea itself.

Sumiyoshi Taisha

Sumiyoshi Taisha

[…] https://thetempletrail.com/huaca-pucllana/ […]