The dusty polluted road is choked up with traffic. As you sit in the torn back seat of a well-used and beat up taxi you view the traffic crawling on the busy section of road you have been stuck on for the last few minutes. Strange three-wheeled tuk-tuk like vehicles that seem to have been thrown together out of old farm machinery vie for position for when the light changes to green. Your taxi just about makes it through the light on the tail of one of the enormous vehicles carrying agricultural produce. The air seems almost brown from the fumes produced by the trucks and factories that line both sides of the road. Soon, you turn off the main intersection and onto a smaller, cleaner road. Your taxi pulls up to a large open square and points you in the direction of a ticket office. You pay the driver and get out into the chill November air of Luoyang in central China. Luoyang, once the capital of China, is home to many ancient marvels, but Guanlin Temple (關林廟 Guānlín Miào) is certainly noteworthy among them.

To fully appreciate Guanlin Temple, you need to know about Guān Yǔ (關于), the iconic general of the Kingdom of Shu at tail end of the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) and beginning of the Three Kingdoms Period (220 – 280 CE). His image is pervasive in China and you can see his long-bearded red-faced grimace in Chinese businesses around the world. Guanlin Temple is the site of his tomb and, since his death in 220 CE, he has been immortalised and worshipped for his strength and loyalty. His story has been enjoyed by generations of readers of the famous 14th century Chinese classic, the Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三國演義 Sānguó Yǎnyì). Known as Lord Guan (關公 Guān Gōng), Guān Yǔ is special in China as he is venerated in the Shenist Chinese folk religion as well as all three of the major doctrines; Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. In Taoism, he is a deity known as Holy Ruler Emperor Guan (關聖帝君 Guān Shèng Dì Jūn), while in Buddhism he is a protector of the dharma called Sangharama Bodhisattva (伽藍菩薩 Qiélán Púsà). In Shenism he is the god of law, policemen, gangsters, fortune and war. He is seen as god of business in Chinese influenced cultures around the world and in Vietnam, a deal made in front of his statue cannot be broken.

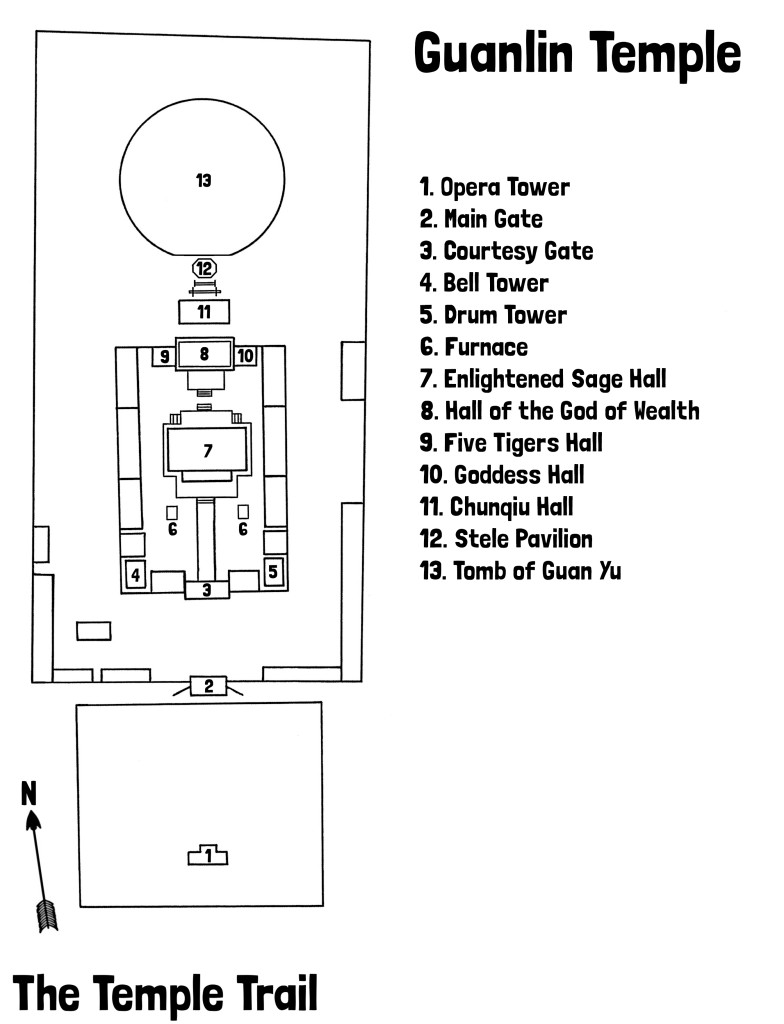

Heading into the square, the first thing you see to your right is the Opera Tower (樓 Wǔ Lóu) and its elevated mini stage. It sits outside the main complex in the middle of the square. In its shadow, old people play Mah Jongg as children run around it. Directly in front of the building, to the south, is the Main Gate (大門 Dà Mén) followed by the Courtesy Gate (儀門 Yí Mén). The temple’s origins are unknown, but the real large-scale construction was done during the Ming Dynasty in 1595 under the Wanli Emperor (萬曆 Wànlì). It was also extended during the Qing Dynasty, when the Main Gate was built and the old front gate of the Ming Dynasty became the Courtesy Gate. Passing through the two red gates you arrive on a flag lined causeway (石獅御道 Shí Shī Yù Dào). To your right and left are the bell tower (鐘樓 zhōnglóu) and drum tower (鼓樓 gǔlóu), but moving forward you come to the glorious Enlightened Sage Hall (啟聖殿 Qǐ Shèng Diàn).

The brazier billows with smoke that you plough through to get into the building, also known as the Hall of Peace (平安殿 Píngān Diàn). Inside, a huge statue of Guān Yǔ stares down at you. Instead of his normal red face, this depiction has a glimmering golden face. Seated on his dragon throne, he is dressed in his Taoist form as Holy Ruler Emperor Guan, shortened to Emperor Guan (關帝 Guān Dì). His attendants, standing either side of him, listen to his celestial decrees. His visage cuts through the dark chamber and the full authority of this deified general can be felt here in the most magnificent of the buildings at Guanlin Temple. Walking around the statues and through the darkened hall, you exit through the back door and out into a courtyard.

The next building in this perfectly symmetrical temple compound is the Hall of the God of Wealth (財神殿 Cái Shén Diàn). This is one of the oldest buildings and it holds imagery of Guān Yǔ with his traditional red face. People come to the hall to pray for success in business. On the left of the hall is the diminutive Five Tigers Hall (五虎殿 Wǔ Hǔ Diàn) and to the right is the Goddess Hall (娘娘殿 Niáng Niang Diàn). The next hall in the sequence is the Chunqiu Hall (春秋殿 Chūnqiū Diàn). It is in a state of minor disrepair and the damp Luoyang weather is clearly something the temple keepers battle on a constant basis. The Spring and Autumn Annals (春秋 Chūnqiū) is a classic Confucian book that was favoured by Guān Yǔ. In homage to this, the hall was built so that his spirit could continue to read every evening. On your left as you enter the musty hall, is a statue of the general reading his beloved book. The statue faces a large bed to your right that holds a sleeping Guān Yǔ, a very unusual depiction of him. This hall is very much for the general’s spirit to relax in and you feel almost as though you are intruding.

Having passed through all of the halls and their dramatically lit imagery, you are now on the threshold of his actual tomb. The scent of cypress trees and incense accents the air as you come to the Qing dynasty gate and octagonal pavilion that stand in front of the huge burial mound. According to the Records of the Three Kingdoms (三國志 Sān Guó Zhì), Guān Yǔ was defeated and executed by Sūn Quán (孫權), ruler of the Kingdom of Wu. He decapitated the corpse and sent the head to Cáo Cāo (曹操), the ruler of the Kingdom of Wei, in order to implicate him in the death of Guān Yǔ, and thereby incur the wrath of Liú Bèi (劉備), the ruler of the Kingdom of Shu and blood brother of Guān Yǔ. Cáo Cāo, however, held Guān Yǔ in very high esteem and had a body carved for his head out of eaglewood (沉香 chén xiāng). He then held a funeral for Guān Yǔ with full honours. The mound that stands before you is where the head and wooden body were interred almost 1800 years ago.

Walking around the tree covered mound, you feel the tranquillity of the last resting place of a man who knew only violence and war. The air seems fresher and the atmosphere quieter and calmer than in the rest of the temple grounds as you make your way past the votive animal statues that circle his tomb. Returning back to the front of the temple, you pass numerous stelae and the two massive furnaces that sit in front of the First Hall. These are used for worshippers to burn “hell bank notes” as well as other ghost money and joss paper (金紙 jīnzhǐ). This is done in order to send riches to their ancestors in the afterlife and to make offerings to Guān Yǔ himself. The fire-blackened openings bear witness to their extensive use.

Leaving the temple grounds and heading back into the chaos of Luoyang, you feel you have touched a part of ancient Chinese history that is so ingrained in the national identity that you see it everywhere. Many Chinese people have lost touch with much of their history, but not with Guān Yǔ. He remains a folk hero to them. Nearly two millennia after his death, this general is still worshipped as a god. He is universally adored by Chinese people all over the planet. By coming to this place, you have become part of that history and experienced the man and the myth for yourself. Hailing a cab, you hope some of Guān Yǔ’s strength and patience have worn off on you as you brace yourself for the traffic of Luoyang’s industrial highway.

That Dam and Pha That Luang

That Dam and Pha That Luang