The Plaza de Armas is entirely enclosed by burnt-brown coloured buildings. A swathe of Spanish-style colonial architecture makes for an impressive vista. The cloisters of the surrounding structures are filled with touts for overpriced tours to Machu Picchu and the other sites in the valleys of the Inca heartland. Apart from turning down their offers, you need also to turn away street urchins who beg you for a few soles. Amid the chaotic scenes of tourists and locals vying for their trade, you move to the centre of the plaza and look around panoramically. Churches impressively demonstrate the Spanish dominance of the local people during the conquest-era. The plaza was the scene of a bloody act of brutality as the last vestiges of the Incan Empire was crushed by Pizarro and his cruel conquistadors. The Iglesia de la Compañía de Jesus on the Plaza now has a statue of Túpac Amaru II; the Incan resistance leader who was drawn and quartered in the square that was known by the Inca as the square of the warrior.

Wandering out of the Plaza de Armas and toward the Mercado San Pedro, you are surrounded by the smells and flavours of the Inca people mixed with a little Spanish influence. The brightly coloured ají (chili peppers), choclo (corn) and potatoes stimulate your visual senses and the strong smells of cooking lure you inward into the bowels of the city that is still known as Qosqo by the native people. Having filled your belly and stocked up on some local Peruvian chocolate, you hail a cab and tell the driver to head to the furthest of four important satellite sites that are strewn alongside the road to the north of Cuzco, the navel of the earth.

The serpentine road winds through the grassy hills towards a place that the Incan elites used as a place of leisure. Tambomachay is a site of uncertain function. The name itself is derived from the Quechua tanpu mach’ay, meaning resting place. Entering the small valley opening, you pass grass fields with donkeys and alpacas doing the gardening. The area looks totally natural and nothing other than the indigenous ladies selling the normal array of wares on the side of the path. Something man-made punctuates the natural hillside. A stone fountain gushes water from its neatly carved spout. Turning the corner, you see the main site; a small, but perfectly crafted set of Incan fountains. The water that spews forth is the natural spring water of this Incan spa.

Water was sacred to the Inca and by bathing in the natural water, they would be blessing themselves in the water that was so important for the fertility of the lands and thereby the potency of the Incan Empire. The perfectly-cut stone blocks fit together with laser precision and the methods used to carve these edifices are still unknown to us. The high status of the site can be discerned from the use of this stone-cutting technique and only other elite sites have these type of constructions.

After basking in the sunshine and the spray of the spouting water, you trudge down the track in the direction of Cuzco. The gently-sloping hills that frame the valleys are home to sheep and alpacas grazing lazily on the green bounty of nature. A human construction juts significantly out of the otherwise curvaceous landscape. Puka Pukara means red fort in Quechua and was an important strategic defence post of the capital. Were you here as the sun was setting, you would have understood the name, as the last beams of light hit the rocky outcrop and turn it red. There is not much left of the fort and after a cursory once over, you wait for a service shuttle at the roadside.

The gutted silver van pulls up alongside you and you jump aboard. Ten minutes back down the road towards Cuzco, you jump out and hand the fifteen-year old conductor two soles. You walk under the shade of the tree canopy to a large set of rocks that form a wak’a (huaca). A wak’a is a sacred site or object in Andean societies that can be man-made or natural. In the case of Huaca Pucllana in Lima, it is a large adobe pyramid, but here it is a collection of large rocks. This in many ways is a primaeval wak’a. This is Q’inqu (Qenqo); one of the most important holy sites in the Cuzco region and a place where some of the most vital rituals were conducted. Q’inqu means zig-zag after the jagged channel that has been carved into the top of the great rock. The site is actually a marriage of natural and artificial. It is a temple carved from a huge standing stone and was a place of both life and death.

Nearing the stone, you descend the hillside and into a circular area. In the centre stands the megalith. It is vastly imposing and you feel the pull of its aura. You approach the heavily carved and modified rock and you see that the top of it is a series of niches and the zig-zag that the site takes its name from. The channel’s use is mostly speculation, but many believe that it carried chicha (corn alcohol) for ceremonial purposes. You arrive at a great cleft in the rock. Threading through it like an Argonaut, you are thrown into the belly of the beast. Here the dark recesses have been carved into niches and in the centre is a stone carved altar. The purpose is unclear, but the general consensus is that solar, lunar and stellar worship was conducted here. Many among the modern Inca and other Andean people still have similar religious practices and it is easy to imagine preserved llama foetuses, other such gruesome offerings and blood sacrifices occurring on the altar. The importance of the site is clear and the Incan elite, wanting to be associated with the gods of the heavens, were embalmed in the cool, claustrophobic passages of Q’inqu.

Bursting into the light, you move away from the enigmatic holy-site and back to the road. Taking you ever downward into the valley, you spot a huge wall from the distance. The sheer size of it doesn’t become apparent until you are almost upon it. The wavy gargantuan wall is almost beyond belief. As you stand next to one of the pantagruelian blocks, you scour your mind for the possible techniques used to carve and transport them. The enormous defensive walls of Saksaywaman (Sacsayhuamán) had more than just strategic significance. In use for over a thousand years, the site name is variously translated as either ‘satisfied falcon’, ‘stone city’ or ‘speckled head’. The last translation is a reference to the site being the head of the puma shaped layout of Cuzco. It has generally been misconstrued as purely a fortress site but, despite also having this function, it was once an even more glorious ceremonial centre that was home to large scale festival activities.

When the Spaniards attacked the site in 1536, the wall was a segregation of the real world and the spiritual acropolis that was situated above the huge stone blocks. After the costly and bloody battle, where even Pizarro’s son was killed, the upper sanctuary of the site was dismantled and used in the construction of colonial Cuzco. Described by contemporary accounts as being labyrinthine, the temple was dedicated to the sun god; Inti Raymi. The Inca emperor Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui (or Pachakutiq) , the ninth Sapa Inca (Great Inca) of the Kingdom of Cuzco, started construction in the mid-15th century and it took the best part of a hundred years to complete. When the conquistadors arrived, it was freshly constructed.

The great walls that you see before you are zig-zags and form the jagged teeth of the great puma’s head. The gigantic blocks are loaded with ritual meaning and are a metaphoric depiction of the lightning god; Apocatequil or Illapa. The three layers of wall are also representative of the three worlds of the Inca cosmology: Uku Pacha (the underground world of the dead and symbolized by the snake), Kay Pacha (the earth surface world represented by the puma) and Hanan Pacha (the sky world of the superior gods associated with the condor).

Climbing up a staircase and above the lightning and clouds, you come up into the skies. Here, you are standing in the space dedicated to Inti. It is here that the Inca emperors would have associated themselves with the god. When Pachakutiq came to power, he promoted the worship of Inti over that of the traditional major god Viracocha. The Inca rulers traced their lineage to the sun god and wanted to reinforce their power in the region. In this regard, Sacsaywaman was symbolic of the power of the Incan ancestors. The acropolis you stand on now is almost entirely levelled. You can make out the foundations of a circular tower. This building, called Muyuq Marka, was a residential site for the emperors. Two other, square, towers were also located among the maze-like streets of the upper sanctuary. Sallaq Marka and Paucar Marka would have been garrison buildings for the elite soldiers who protected the emperor. The key building in the compound would have been the Temple of the Sun, regarded by many scholars to have been the highest status religious structure in the whole empire.

From this high point you look across the plaza of Sacsaywaman, Chuquipampa, to a large mass of stone. There is a circular mound and a natural rock that has the appearance of a waterslide. It is aptly named the Rodadero (sliding place). This is another sacred wak’a and once held a throne for the emperors as they looked upon festivities during the worship of their ancestor Inti. The circular mound immediately behind the Throne of the Incas is the Qocha Chincanas and is where Incan elites would have been laid to rest, thereby empowering the Inca bloodline of the man who sat on Rodadero. Out of your sight is the sacred spring; Calispucyo, where initiation rites would have taken place. The entire site of Sacsaywaman was designed to be a defendable, self-contained citadel for the elites that could hold up to 10,000 people in its strong ramparts. The Incas had not expected to encounter the bloodthirsty conquistadors, and the walls that seem so strong to you even today, were swiftly penetrated by the modern warfare of the Spaniards.

In the background to your view lies the body of the puma, the navel of the world; the glittering golden city of Cuzco. Walking from the jaws of the cat, you move down the valley into the city itself. The moderately steep incline takes you past agave plants and old houses that were built during the 16th century remodelling of Cuzco by the Spaniards. Past restaurants serving the Incan delicacy of cuy (guinea pig), your path snakes tightly past remnants of Inca palaces. The signature stonework gives away its origins when compared to the rather crude Spanish workmanship on the neighbouring buildings. The object of your trajectory lies beyond the Plaza de Armas on the Avenida del Sol, under which runs the sacred Saphi River. An elevated church marks the spot.

Something else lives with the Convento de Santo Domingo however. Something much older can still be seen regardless of the parasitic building that was tacked on top of it by the religiously fervent Spaniards. Cuzco was the centre of the Incan universe. The chakana (Incan cross) is a symbol of the three worlds of the Inca cosmos and looks like a stepped cross. It is a charm worn by native peoples in the Andean regions. In its centre is a hole that represents the doorway that connects these three realms. That nexus is Cuzco and in the heart of the centre of the universe, the remains of the most spectacular temple in the Tawantinsuyu (Inca Empire) rest. Semi-hidden by the convent, Qorikancha, the ‘golden palace’ honoured both Viracocha and Inti, but also housed temple buildings dedicated to the other major sky gods.

As you approach the Olympian complex, you are awe-struck by the second huge Incan wall of your day. This one is a work of true artistry. The blocks are smaller than those at Saksaywaman, but there is a more refined hand at work. The wall was uncovered during the 20th century reconstruction of the convent and is fronted by the Solar Garden that extends to the avenue and underground river. It once had a golden rim that capped the top of the wall and marked the opulence of the buildings it contained. Walking around the building to the entrance, the colonial doorway stands where the original entrance once stood. The small plaza that it faces was once part of the much larger Intipanpa (Sun Plaza). In its earlier days, the complex was variously known as the Intiwasi (Sun Tempe) or Intikancha (Sun Palace). The name Qorikancha was introduced by Pachakutiq and was the name the Spaniards would have heard.

Entering the main door, you are very much in a Spanish Catholic building. There is nothing to suggest otherwise. You make your way through beautiful European corridors and chambers until you are in the main square of the much diminished sanctuary. After seeing the European architecture, you are surprised by what you find here. The site was originally divided into the temple of the sun and the temple of the moon. Most of what was the temple of the moon, that worshipped Mama Killa (Mother Moon), the wife of Inti and daughter of Viracocha, was destroyed by the colonialists. What you are amid now was the Temple of the Sun. Walking over to the northern side of the courtyard, the remains of some Incan trapezoidal buildings harken your arrival. The wonderful structures that have the same high-level stonemasonry as the outside wall are sub-temples. Entering them, you see holes in the walls and niches that would have been coated in sheets of pure gold. These were extorted out of the Inca by the Spaniards, who demanded a ransom for their captive, the last Sapa Inca; Atawallpa. The people would have been heartbroken as Pizarro’s men melted down the decorative gold, which only had spiritual significance to the Inca, and turned it into ingots for transportation to Spain. Particularly upsetting would have been when they smelted the enormous golden sun disk that represented Inti.

As you wander through the cloister rooms of the Temple of K’uychi (the rainbow) and the Chuki Illapa (temple of the storm god), you see from what remains how this temple was described as fabulous beyond belief by early Spanish accounts. The temples are now barren, but the workmanship has lasted. These sub-temples were part of the sanctuary of the sun, as they are considered come under the domain of Inti. The rainbow, as it emanated from Inti, was adopted by the Sapa Inca on the Unancha (rainbow flag of Cuzco). Moving around the complex, you come to another, larger trapezoidal building. Ironically, the ‘modern’ Spanish buildings have needed reconstruction work on a number of occasions, whereas the native Incan architecture has withstood numerous earthquakes. The building you are now in is part of the Temple of Mama Killa (the moon) and would have had silver panels in complement to the golden panelling of the sun temple. The Temple of Ch’aska (Venus) and the Stars is still a magnificent building. The large and originally very decorative building with its abundance of tabernacle niches, was clearly a very important part of the complex. The stars were considered to be the maidservants of Mama Killa and they were looked to as predictors of the future, while Ch’aska was the protectress of virgins. The chamber here played a significant role in the solar and stellar observatory function of Qorikancha. The complex once measured not only the procession of the stars, but also the solstices and equinoxes. They used forty seques (lines) that emanated from the centre of the sanctuary marking its place as the centre of the empire and Inca universe.

On the balustrades of the temple looking out over Cuzco, you have the view that only priests and the elite of Incan society would have been privileged enough to have. The water channels of the temple would have poured forth down to the river now covered by the avenue. The town is very pretty with its low-rise colonial buildings lovingly preserved by a mostly native population. Despite having been conquered, the Inca blood runs strong in the veins of the local people. The lost sun disk can be found remade all over the city and the rainbow flag of the Sapa Inca once more flies from the flagpoles. Cuzco is a city that, despite the heavy tourism, or indeed because of it, has rediscovered its identity. It has gone through a revolution. Since the mid-twentieth century, indigenous rights have been bolstered and their culture, which remained simmering under the radar, has boiled over and can be seen proudly displayed everywhere. It would take a blind man not to see the Inca legacy in every nook and cranny of Cuzco. What was taken away by Pizarro never really left; it stayed in the hearts of the proud Andean people who have inhabited this magical valley for millennia.

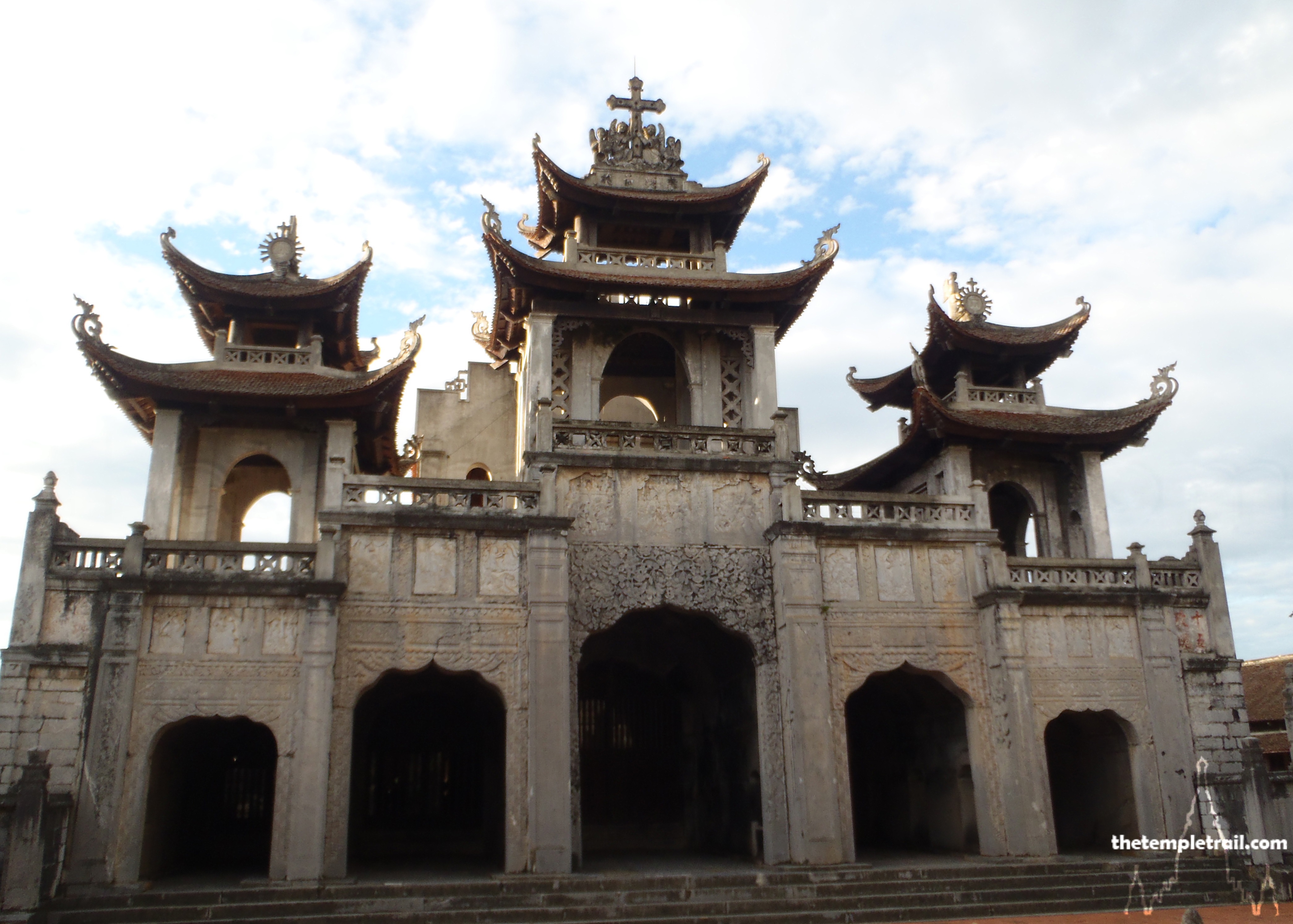

Phát Diệm Cathedral

Phát Diệm Cathedral