Celebrated by almost everyone of Chinese descent, this is the major festival in the Chinese diaspora. Known as Spring Festival (春節 Chūnjié) in Mainland China, but simply as Chinese New Year (農曆新年 Nónglì Xīnnián) to those in Hong Kong and in Chinese communities around the world. Even outside of the Chinese community, people around the world know of the twelve animal zodiac. The world at large is quite familiar with the animals and their various properties. Ask any school child from most countries and they can tell you which animal they are. Beyond this, people not of Chinese descent, usually know little more. The real question is does the historical and mythological significance resonate among the people of modern Hong Kong, or is it simply a nice celebration to ring in the new lunar year?

Mythologically, the story involves a beast who ravages the people being subdued. I was told the story of the Nian (年獸 Nián Shòu) by a young mother from Guangzhou who has lived in Hong Kong a great many years. The Nian is a beast that lives in the mountains. Long ago, the Nian would appear in a village at the beginning of spring and attack the people, particularly children. The people of the village used bright red coloured things and lit firecrackers and the Nian became scared and never came back. In order to keep the Nian away, each year, at the time of the beast’s impending attack, they would repeat the custom.

If we investigate this story further, we find that it is a widespread folk story that explains many of the key elements of Chinese New Year. The Lion Dance that you see being performed at this time of year, while having early origins in the north of China, is very different in the south and is said to have strong connections to the Nian. The use of firecrackers (now banned in Hong Kong) scares away evil spirits. The colour red is very lucky and worn universally. The red is found on the firecrackers (爆竹 bào zhú), the lucky “lai see” pockets filled with money (利事 lì shì), the talismans (符fú) and lanterns (紅燈 huā dēng). The red element comes from a folk story in which the great Taoist patriarch Hóngjūn Lǎozǔ (鴻鈞老祖) subdues the Nian by wearing red undergarments. He then reports this to the villagers who start using red as a protective colour.

A recent university graduate who lives in Tai Wai, near to the Che Kung Temple, reported another Chinese New Year tradition. She said that her family always visit the temple on the third day of the New Year, as this day is symbolically seen as being a day of argument. It is thought that you are very likely to fight with others, so care is taken not to invite anyone to your home and to keep contact with others down to a minimum. By visiting the temple, they make offerings and generally stay away from too much human interaction.

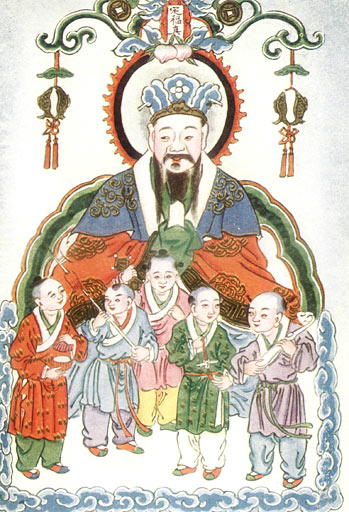

The days of the New Year each have a significance. The days before the New Year are a buzz of activity. Five days before the New Year up until midnight on New Year’s Eve, Hong Kong explodes with Flower Markets, Fa Shi (花市 huā ), a remnant of the Ming Dynasty. Rather than just sell flowers, a whole variety of New Year related goods can be found. This is an enormously popular event to attend, especially on the last night when people ‘walk the year night’. The Chinese also scramble to brush away the dirt, repaint their houses and have their hair cut all before the beginning of the New Year. While most hold to the fact that it is unlucky to cut the hair in the beginning of the New Year and that it is lucky to clean your house, many don’t know exactly how the tradition developed. The origins of the practices lie with the story that the Kitchen God, Jou Kwan (灶君 Zào Jūn) or “Stove Master”, ascends to heaven to report the activities of the household to Yuk Wong (玉皇 Yù Huáng), the Jade Emperor. In the past, the doors to the house were closed on the last day of the old year and not opened again until the morning of the first day in a ceremony called Opening the Doors of Fortune – Hoi Choi Mun (開財門 Kāi Cái Mén). While this practice is not common in Hong Kong, the house is still prepared for the New Year.

The first day is then all about welcoming in good spirits and deities and banishing evil ones. This is when all of the methods used for scaring away the Nian are employed. This is when lai see are given out. The young mother told me that her family do not eat meat on the first day and that they are fully vegetarian for the day. This is a practice that comes from Buddhism, as they wish to start the year without harming others. This is taken so seriously, that they do not use any knives on this day. They have to chop and prep all of the food on the night before. In her family, which hail from Guangzhou, they then exclaim ‘Hoi Nian’ on the lunch of the second day when they finally take meat to open the year.

In Hong Kong, one major religious practice that attracts thousands of people is the making of offerings at Wong Tai Sin Temple on the first day of the New Year. The rapid growth of the cult of Wong Tai Sin (黃大仙 Huáng Dàxian), a god brought from the Mainland in the early 20th century owes much to the firm belief that the god can ‘make every wish come true upon request’. The temple now opens on the eve of the New Year so that worshippers can make their first offerings of the year. Sik Sik Yuen, the organisation that administers the temple has even made an android app to help regulate the huge influx of visitors. Talking to Hong Kong people, you find that even those who are not religious often make the journey to Wong Tai Sin Temple during the New Year celebrations.

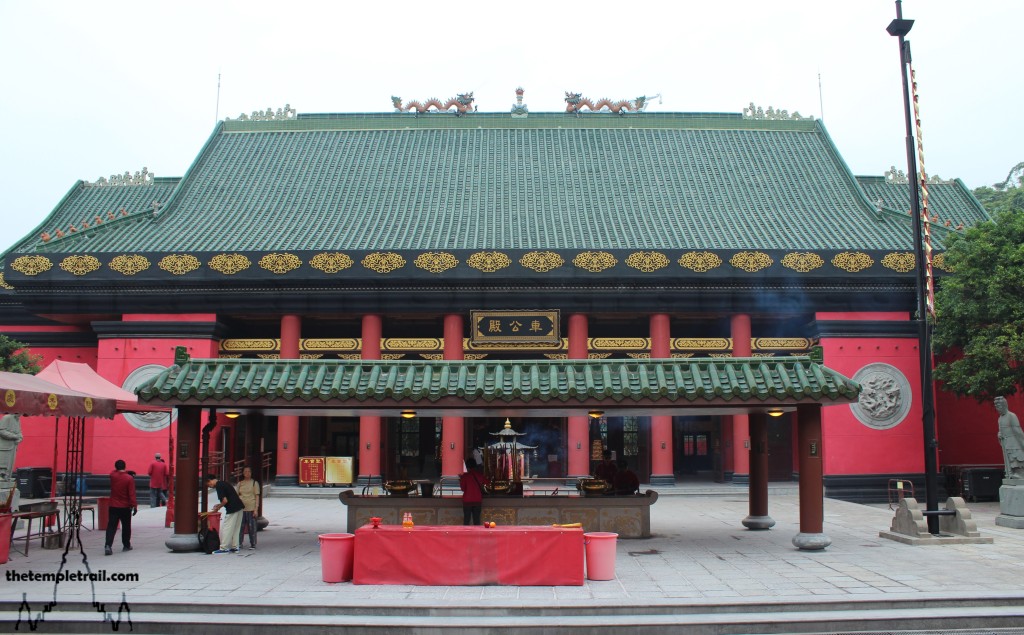

The second day is seen as the actual beginning of the New Year and is also the birthday of Che Kung (車公 Chē Gōng). While this is officially the day to visit a Che Kung temple, many people, much like the recent graduate’s family, prefer to go on the third day. Probably for the same reasons she stated. Che Kung actually has four birthdays in total each year, but this is the most popular of them. Che Kung is a protective god who was a military commander of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127 – 1279 CE). He is associated with the flight of the last two boy emperors of the dynasty to Hong Kong when the Mongols sacked the former capital city of Hangzhou. As a respected military officer, he has powers of protection, suppression of chaos and the ability to cure diseases. The main temple of Che Kung is in Tai Wai and that is where a representative of the Hong Kong government goes on the second day to draw Kau Cim sticks (求籤 qiú qiān). These bamboo sticks are shaken from a container until one falls out. The number on the stick corresponds with a fortune scroll. The government official performs this task (an everyday occurrence all over Hong Kong and China) on behalf of the entire region. The result, whether good or bad, is taken quite seriously by many in Hong Kong.

The third day is known as Red Mouth, or Chek Hau (赤口Chìkǒu), to the Chinese. This sounds like chek gou (赤狗 chì gǒu), meaning red dog, which is another name for Biu Nou Ji San (熛怒之神 Biāo nù zhī shén), the God of Blazing Wrath. Rather than fight, it is better to go and get some divine assistance. While many flock to pray to Che Kung, others go to ask for financial help from Choi Sun (財神 Cái Shén), the God of Wealth, even though his official birthday is on the fifth day. Many people often make offerings at the Man Mo Temple in Sheung Wan. This temple has both a martial and a civil god as the main focus of worship. Parents go and ask for good academic results on behalf of their children there. Another important god for the New Year is Yuk Wong, the Jade Emperor. Even though his birthday traditionally falls on the ninth day, you are hard pressed to find anyone in Hong Kong who celebrates this and it is much more prevalent in Hokkien communities in Fujian Province and Taiwan.

One remnant of the importance of Yuk Wong in Hong Kong is the appeasement of the Tai Sui (太歲 Tài Suì), the Emperor’s sixty generals who take it in turns to look after the world for a year. The sixty-year cycle of Tai Sui allows for five complete cycles of the earthly branch. The twelve year cycles are the familiar animal zodiac that is best known around the world. What non-Chinese often don’t know is that each time the animal’s year comes round, the element which governs that animal shifts between the Ng Hang (五行 Wŭ Xíng), or five elements. The five elements are water, wood, fire, earth and metal. So a person born in 1980, was born in the year of the Metal Monkey. The sixty year cycle of the Tai Sui represents a full cycle of all of the earthly branches through all of their elemental influences. Even though the New Year marks the shift of responsibility to the next general, if you go into a Chinese temple in Hong Kong at any point in a year, you will see people making offerings to the general of the current year. While this is most commonly practiced by the older generation, the younger people in Hong Kong are very familiar with it.

The entire set of festivities culminate in the Yun Siu Jit (元宵節 Yuánxiāo Jié) festival on the fifteenth day. In English it is usually called the Lantern Festival and it takes place long after everyone has returned to the daily grind of work. Lanterns are hung everywhere and while many are the traditional red ones, in Hong Kong there are large elaborate displays of lanterns in themed tableaux ranging from folklore to contemporary cartoon characters. In Chinese, the festival is actually named after the little sweet rice dumplings in soup they eat on this day called tong yun (湯圓 tāng yuán). While the Lantern Festival probably originates in ancient worship of the old god Tai Yat (太一 Tài Yī), the pole star, people do not associate the festival with that these days.

When asked, Cantonese people can tell you a lot about the more modern Choi Dang Wui (猜燈謎 Cāi Dēng Mí) Lantern Party. These large scale parties are organised by local dignitaries, district organisations and local governments to entertain the people. Many lanterns are hung up with tags hanging from the bottom of them. These tags each contain a riddle. If you can solve the riddle, you take down the tag and present it, along with your answer to one of the hosts. If you are correct, you will be given a prize. This speaks to the very soul of the Chinese people, as the quality of cleverness is valued highly in Chinese culture. This is evident in the most popular heroes of the folk stories who win by guile rather than brute force.

Another element of Chinese New Year that is lost on the majority of the modern population of China and Hong Kong is the agricultural meaning. The name usually given to New Year in mainland China is Chūn Jié, meaning Spring Festival. It is also called Nónglì Xīnnián (農曆新年), meaning Traditional Lunar Calendar New Year. Nóng (農) means agriculture, so a more direct translation would be agricultural calendar new year. Despite the language links to the land and farming, the young urban Chinese don’t fully appreciate the rural significance. Much like the ancient spring celebrations in almost all cultures around the world, the festival was intended to mark the end of the dark winter months and the rebirth of life. While the idea of winter ending and spring beginning is obvious to everyone, most modern Chinese, much like the modern people in nearly every other country, don’t feel the joy that their ancestors did at this time. The symbolic cherry blossom decorations, mandarin trees and flower pots adorn shopping malls all over Hong Kong, giving a nod to the seasonal transition, but there is no longer a terrible food shortage and struggle through winter as there was in the past. This, thankfully, is the case in many countries, but in Hong Kong, where the farms are so far removed and the food supply is so diverse and constant, it is markedly obvious.

One tradition that does carry forward and has a connection to the nature facet of the New Year is the practice of visiting the Wishing Trees at Lam Tsuen in the New Territories. While visited throughout the year, many visit during the Lunar New Year celebrations in order to make wishes at the trees. In the past People wrote their wishes on red joss paper and then tied one end to a mandarin orange which they threw upward into the tree. If the paper stayed in the tree, their wish came true. Although people are now discouraged from throwing their wishes directly onto the centuries old trees in fear that they will be damaged, they still visit and hang their wishes on a special rack next to the trees. In recent years, as a way of allowing the tradition to return, light-weight plastic mandarins are sold so that people can throw their wishes onto the trees once more. There are other wishing trees all over the region, showing the deep tradition of tree worship across Hong Kong. The trees themselves show a connection to the earth and nature and they are often tied to the district god, Pak Kung (伯公) or She Kung (社公). The mandarins also have a nature connection, but are mostly popular because the name in Chinese is a homophone of the word for luck. Despite the fact that many Hong Kong people no longer actively worship trees and local spirits, the tradition survives through the folk beliefs surrounding luck.

One could make the argument that, while there is somewhat of a disconnect from the religious and spiritual elements of the Chinese New Year, culturally, nothing much is lost to the people living in modern Hong Kong. Like any other modern society, the ritual elements of the past have transformed into a, no less relevant, but more secular set of activities. While there are ties to the original observances and elements of those more formal and religious rites, Hong Kong has made the Chinese New Year a more contemporary and inclusive festival which respects tradition, yet embraces the modern.

Many thanks to all who answered my questions about Chinese New Year and gave me their take on the festivities, but particularly to Mandy Chen and Tracie Lee who provided great stories. Kung Hei Fat Choi!

Kowloon Masjid and Jamia Masjid

Kowloon Masjid and Jamia Masjid