Walking amid the smells of freshly baked nang bread in the ancient city of Kaifeng, it is hard to imagine that it was once the capital of China. Its newly refitted city walls enclose the hustle and bustle of the old city that was oddly positioned on an almost indefensible piece of land. The city has seen centuries of expansion and destruction and has a hugely diverse religious landscape. Buddhists, Taoists, Shenists, Muslims and Jews have called this city home since antiquity. The mix of cultures has forged a varied and exciting social and culinary town that has more than just food for your stomach. Wandering past street stalls selling lamb skewers you arrive at a large red gateway. The guardian lion statues of Temple of the Chief Minister (大相國寺 Dà Xiàngguó Sì) hail you as you stand between them looking through the portal. Inside, many treasures await you.

Originally a private residence in the Kingdom of Wei (220 – 265 CE), Dà Xiàngguó Sì was founded as a temple in the city of Kaifeng during the Northern Qi Dynasty (550–577 CE). Originally called Xiàngguó Sì, it was a very important temple for the transmission of Buddhism in China. It was destroyed through warfare and rebuilt during the Tang Dynasty in the 7th century CE by a monk named Huiyun. Emperor Ruizong (唐睿宗 Táng Ruìzōng) of the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE) named the temple Dà Xiàngguó Sì as he was originally the King of Xiang. During the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 CE), the temple reached its pinnacle as an international centre for Buddhism. Foreign visitors came for cultural exchanges and the temple grew into a huge complex of buildings with over 10,000 monks and more than sixty buildings. The temple was the favourite of the imperial household and the emperor himself selected the abbot of the temple. Dà Xiàngguó Sì is where the emperor performed the rites of giving thanks to heaven and the annual advanced scholar (進士 jìnshì) ceremony to award titles to those who passed the Imperial Examination (科舉 Kējǔ). After the Northern Song Dynasty fell to the Mongol invasion, Dà Xiàngguó Sì never quite reached the level it had during its halcyon days in the 13th century AD where it had an area of 500 mu (more than 33 hectares). After being damaged by floods in the late Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644 CE), the temple was abandoned and restored once more during the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912 CE).

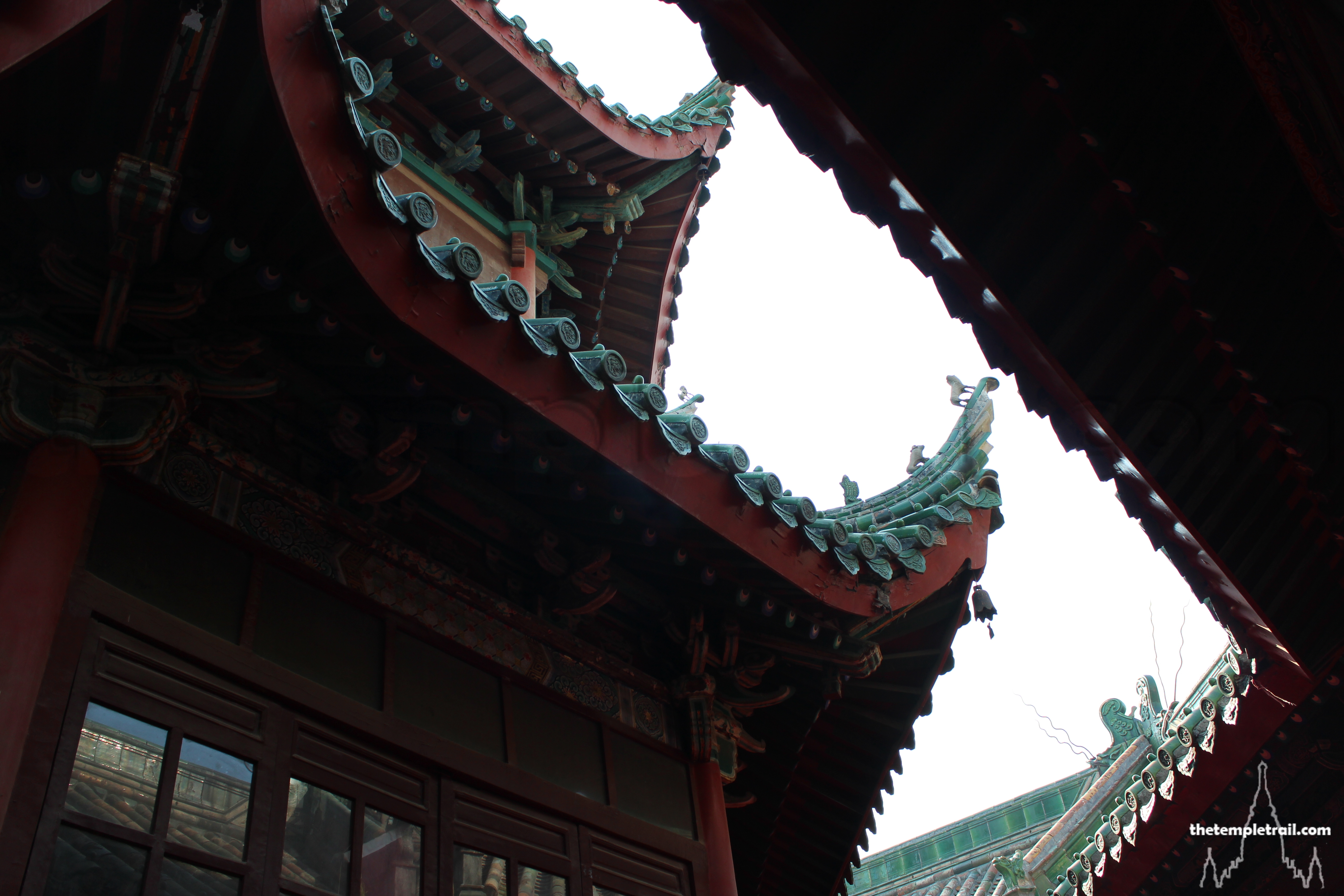

The temple you see ahead of you is mostly from the Qing Dynasty and walking through the doorway of Mountain Gate (山門 Shān Mén), the temple guardian statues’ grimacing visages glare down at you to remind you that they are protecting the temple. Exiting into the light of the first courtyard, your eye is immediately drawn to a statue of a man uprooting a tree. This gargantuan bearded man is Lu Zhishen (魯智深 Lǔ Zhìshēn); a fictional character from the great Chinese classic, The Water Margin (水滸傳 Shuǐ Hǔ Zhuàn). He is a military officer, turned monk, turned outlaw. In the epic story, Lǔ Zhìshēn is sent to Dà Xiàngguó Sì by the abbot of another temple, as they cannot control his drinking and meat eating. Lǔ Zhìshēn is put in charge of the temple garden and the statue depicts him uprooting a willow tree; a feat that secured his fame. He represents loyalty, justice, strength and brashness.

On your right and left are the drum tower (鼓樓 gǔlóu) and bell tower (鐘樓 zhōnglóu) of the temple. These are the most modern buildings of the temple, built in 1992, and both contain small stalls selling prayer beads. These two towers are festooned with older artefacts to lend them more gravitas. The five-ton bell in the bell tower is from the Qing Dynasty and is more than two metres tall. The sound of the bell on a frosty day is an iconic experience of Kaifeng.

Heading into the Hall of the Heavenly Kings (天王殿 Tiān Wáng Diàn), which is dead ahead of you on the temple’s north to south axis, you are once again ogled by stern looking statues. These are the Four Heavenly Kings (四大天王 Sì Dà Tiānwáng) who protect Buddhism and the world. The hall also contains a statue of the Sackcloth Monk (布袋 Bùdài), also known as the Laughing Buddha (笑佛 Xiào Fó) and behind him (as is customary in China), stands a statue of Skanda (韋馱 Wéituó). Wéituó is a Dharma protector and he was brought into the Buddhist pantheon as a Bodhisattva after he rescued Buddha relics from some demons. Leaving the hall you move north under Wéituó’s unfaltering gaze.

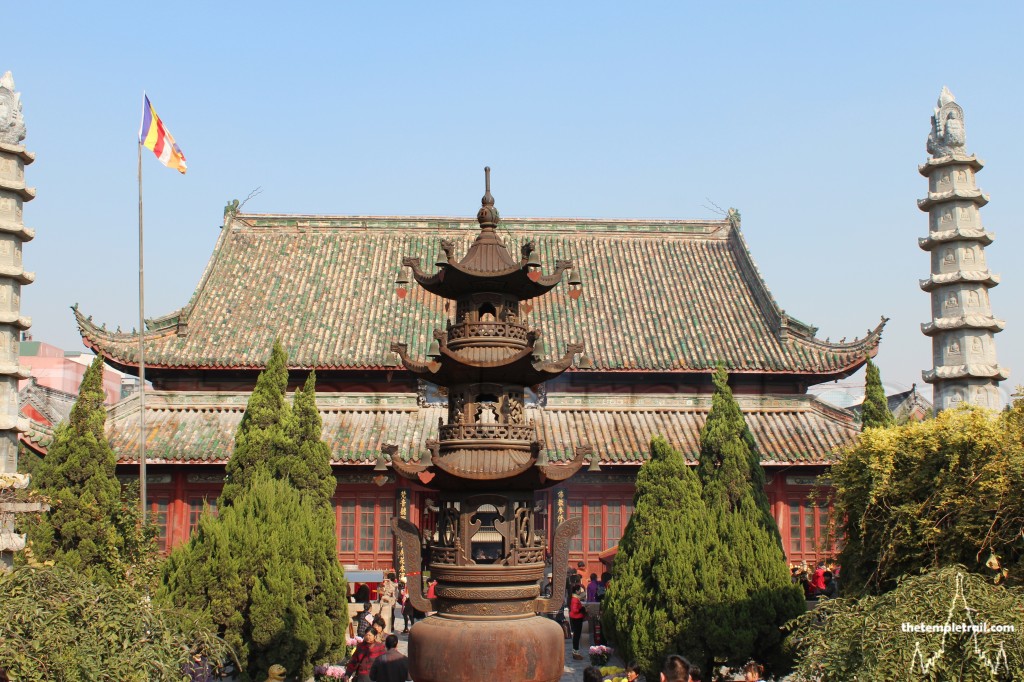

You cross a bridge over a small body of water called the Saving Being Pond and past a towering incense burner. In front of you is the Throne Hall of the Great Hero (大雄寶殿 Dàxióng Bǎodiàn). Choking on the clouds of joss smoke, you enter the shady chamber coughing and spluttering. Finally, catching your breath, tranquility descends upon you under the watchful eye of the historical Buddha, Śakyamuni (释迦牟尼 Shìjiāmóuní). His statue is flanked by Amitābha (阿彌陀佛 Ēmítuófó), the Buddha of the Western Pure Land and Bhaiṣajyaguru, the Medicine Buddha (藥師佛 Yàoshīfó). The three solemn, yet peaceful statues look out upon those who have come to pay them homage. Walking around the statues to the back entrance of the hall, a golden sculpture of Guānyīn (觀音), the bodhisattva of mercy, sees you out of the building and into the next courtyard.

On the other side of the courtyard is The Hall of the Arhats or the Octagonal Glazed Hall (羅漢殿 Luóhàn Diàn). This hall is the main focal point of activity in the temple and is famed for the seven metre tall thousand-hand, thousand-eye Guānyīn statue that occupies the central chamber. Entering first into an outer corridor that circles the central chamber, you pass hundreds of small statues of arhats (saints). Travelling in a clockwise direction, you are scrutinised by all of the colourful statues before heading out into a ring-shaped courtyard that encircles the main hall. Coming into the hall, the huge wooden statue occupies centre stage. Her four heads each look out of one of the doors of the hall; the cardinal directions. The thousand arms, each with an eye on it, were a gift from Amitābha so that she could reach out to all those in need. Carved out of a single ginkgo tree trunk during the reign of Emperor Qianlong (乾隆帝Qiánlóng Dì) of the Qing Dynasty in the 18th century, the piece took 58 years to carve and actually has 1048 arms. It is a master class in Qing artistic perfection. Looking up at the serene faces, you can’t help but stand in awe of the bodhisattva.

After taking in the hall, you move yet further north to the Hall of Tripitaka (藏經樓 Cángjīng Lóu), the sutra repository. You circle back through the complex to the front gate. Passing numerous shops in the rooms on either side of the temple, you see how it has not been able to withstand the modern preoccupation of making money. Commercialisation has reared its head in many Buddhist temples in China and Dà Xiàngguó Sì is no exception. Despite this, it is still a beautiful gem. In its heyday, it was said to have had the ‘glitter of gold and jade’ and to ‘surpass the rosy cloud’. Today, regardless of its commercial aspect, it still glitters and holds a host of wonders among its colourful buildings.

Cao Đài Holy See

Cao Đài Holy See