The morning sun is just beginning its slow roast of the Singaporean streets as you step out of the café. Your breakfast of kaya toast with soft boiled eggs, washed down with sweet coffee has left you feeling elated. Still savouring the last remnants of flavour, you walk through a shopping complex full of places to eat and view the restored gate of the former Hokkien Chui Eng Free School. Walking through a hotel, your stroll takes you through reused space that was once the oldest Chinese temple in Singapore. On the edge of Chinatown, you take your time to explore the tiny Fuk Tak Chi Temple. Built by Hakka immigrants in 1824, the temple was dedicated to the Malay-Chinese god, Tua Pek Kong (大伯公 Dàbó Gōng – Grand Uncle). The god, who is worshipped in local Shenist folk religion, was a Hakka (客家) clansman whose journey by boat to Sumatra was blown off course and landed in Penang in 1846. He was deified by the small population of the island after his death. This temple fell out of use over the years and in the late 1990s it was renovated and converted into a small museum with some nice resting spots. Taking advantage of the opportunity, you sit in the shade looking at the pretty roof tiles above you while gathering strength for the already smouldering pavements that await your footfall.

Having delayed the inevitable, you venture out into the Chinatown streets. Taking Telok Ayer Street, you pass the Ying Fo Fui Kun (應和會館), a Hakka Clan Association. The small lions that guard the front seem too small for the substantial clan house. It is the first of many buildings in the area that remind you that Singapore’s majority is the Chinese population from many different areas of China. The old Chinese shophouses that are so iconic of Singapore line the side of the road. Their pastel colours covering various states of renovation and dilapidation. Using them as good shade, you continue along the street and past the distinctly non-Chinese Nagore Dargah. This is a South Indian Muslim shrine that stands out from the rest of the architecture on the street. Founded in 1828, the beautiful building is elaborate with its arched doors and windows and the miniature palace that sits above them. Resting next to this building is one that surpasses it in terms of adornment. The building that has been your main target since finishing your breakfast. The fantastic Thian Hock Keng (天福宮), or Temple of Heavenly Bliss, is the most important and oldest Hoklo temple in Singapore. The Hoklo (福佬), or Hokkien, from Fujian in China, are the largest of the Chinese groups here, making Thian Hock Keng the most significant Chinese temple.

Built between 1839 and 1842 by the Hokkien clan, the temple sits next to its brother, the smaller Temple of the Heavenly Jade Emperor (玉皇宮 Yù Huáng Gōng). It was constructed in traditional Southern Chinese style and no nails were used to hold the tiles, timber and stone together. Under the management of the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, it was fully renovated in the late 1990s. The temple is now much bigger than the humble joss house that was erected in 1821 by Southern Chinese seafarers on what used to be the waterfront. The tiny original was built to thank the goddess Ma Cho Po (媽祖 Māzǔ or 天后 Tiān Hòu), a sea goddess from Fujian province and patron of the Hokkien people. As the journey across the sea was treacherous, the grateful junk sailors wanted to give praise upon their arrival. This they did in droves. Sir Stamford Raffles, the British statesman, founded Singapore in 1819 and soon after him came Chinese merchants looking to make their fortunes. These early pioneers founded the joss house and by the 1830s large numbers were landing in front of the small temple. These southern Chinese, disillusioned with the neglect they were receiving from the emperor in the north and the difficult economic and political climate of south China, descended on Singapore. Wealthy Hokkien merchants such as Tan Tock Seng who came from Malacca in Malaysia (one of the main patrons) donated large sums of money to construct a larger temple in the 1830s. Money was collected also from junk boat owners and soon the building works were under way. Materials and craftsmen were brought from China and in 1840 the statue of Ma Cho Po, as the goddess is called in the Hokkien language, arrived from Amoy to be enshrined in the new main hall. The new temple, built of pine, ironwood, granite and colourful tile reflected the sudden fortunes and opportunities available to the immigrants and was a status symbol for the community. Upon arriving, newcomers could see that there were possibilities for them in Singapore. The now landlocked temple was an important focal point for the community and it acted over the years as a meeting place for the Hokkien Clan leaders, performance venue and school. During the Japanese occupation in the Second World War it was a vital symbol for the resistance movement.

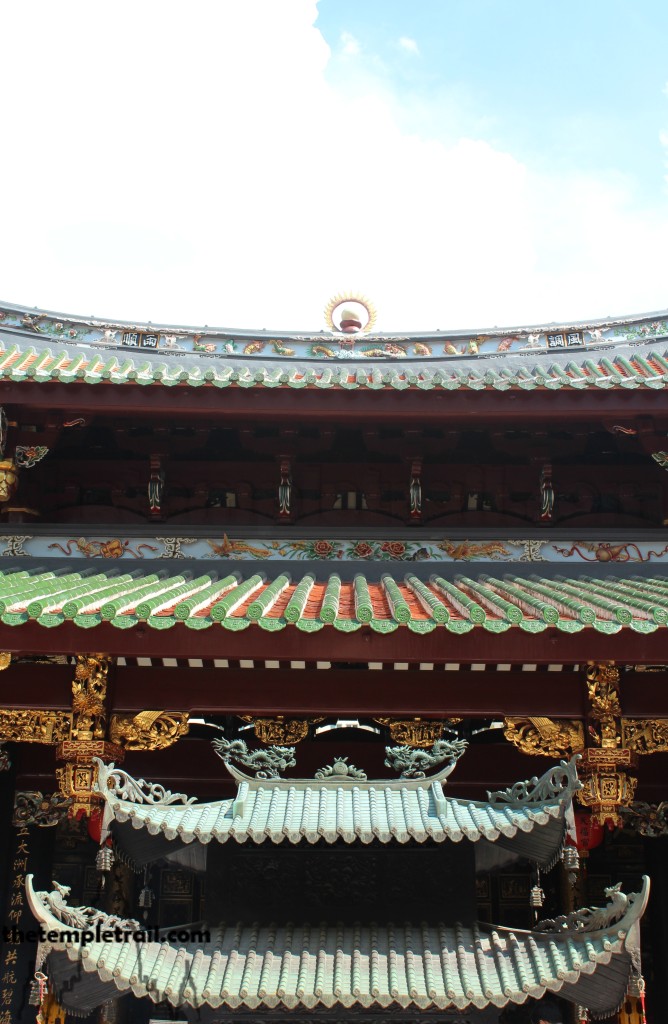

Approaching the building, you note the building work that is happening in the small compound on the corner of the temple. Above the scaffolding and barriers, you see ornate roofs and an exquisite octagonal pagoda. The pagoda is the Keng Teck Huay Pagoda and it sits in what used to be the Keng Teck Whay, a self-help organization for Hokkien-Peranakan merchants that was founded in 1831. The set of buildings that occupies the space were built between 1847 and 1875 in the south Chinese Minan style, like the rest of the main temple structures. The main building at the back, which is presently out of bounds, was an ancestral hall. The buildings were acquired by a Taoist organization, and will soon be opened as the Temple of the Heavenly Jade Emperor. The roof on the pagoda has been renovated to fit in with the chien nien mosaic sculpture (剪黏 jiǎnnián) stylings on the swallowtail eaves of the main temple buildings. Your view across the wonderful decorative roofs of the entire temple complex is of colourful chien nien dragons and phoenixes flying and playing on the corners and ridges.

You finally stand before the main entrance hall of Thian Hock Keng. The stone and wood, embellished with gold are stunning and after taking in the elaborate dǒugǒng (斗拱) roof supports that are carved as heavenly beings and the pair of stone lions that guard the main door, you step up onto the stone entrance porch. The porch is raised and made of stone and is a remnant of when the temple sat on the water front. The land in front of Telok Ayer Street has been reclaimed, but once there was the need for a barrier to prevent the high tide sea water entering the temple. On the porch, you look at the gold lacquered and painted door sentinels. Each of the doors in the five frames has a door god on it, except for the main ones, which have dragons on them. These martial and civil gods are responsible for keeping wicked spirits out of the temple. On either side of the dragons, the four door gods are eunochs holding money bags. These welcome in the good, while the military ones exorcise the bad. The decoration surrounding you is dazzling. Flowers, peacocks, tigers and swastikas fill your vision and, stepping through the dragon doors, you make it through the guardians’ vigil to the inside of the complex. The hall, you stand in is completely open on the inside. Looking to your left, you see a large granite tablet embedded into the wall recording the temple’s history.

From the shade of entrance hall, you look out to the main courtyard of the temple. The sun brightly shines onto the tiled floor and before the imposing and beautiful main hall of the temple rests a bronze brazier for incense. The main hall that you observe in ahead of you is a masterpiece. In the distinctive Mǐnnán (閩南) style with swallowtail eaves, the colours are astounding. The bright and complex design of the exterior is like a beacon in the sunlight and as you move into the rays, you can’t take your eyes off the ornamentation. As you come under its shade, you peer in to the darker and simpler interior with its ironwood pillars. The Western style floor tiles add some pattern and were added in 1906. As you step in, your eyes are drawn the focal point of the hall; the main altar. Framed in golden carvings and guarded by her two demonic watchmen, the goddess is represented by two statues. The brightly coloured large one is more modern, but the darker and smaller one is the original that came from Amoy in the 19th century. It is said to have been blackened by years of joss smoke, but in all likelihood, it was dark before it even came to the temple.

Ma Cho Po, or Māzǔ (媽祖) as she is commonly known around Asia, is an important sea goddess in all of the Chinese sphere of influence. She is said to have saved her father and brother from a typhoon when she was a mortal in Fujian province. Her human name was Lín Mòniáng (林默孃), meaning silent girl because she did not cry when she was born. Upon attaining immortality she was granted the title Tiān Hòu, Empress of Heaven. She is always accompanied by her two guardians, Thousand Mile Eyes (千裡眼 Qiānlǐ Yǎn) and Favourable Wind Ears (順風耳 Shùnfēng Ěr), demons who she quelled and gained as servants. Due to her divine powers and her special abilities regarding seafaring, the ocean travelling Chinese have worshipped her since her immortality in 10th century. A thousand years later, not so many people travel by sea, but the goddess is still revered for safety in travels, and as a patron of the southern Chinese.

To the left of the goddess is a statue of the Life Protection Emperor, (保生大帝 Bǎo Shēng Dà Dì), a god of medicine. Also a mortal from Fujian province, he was a doctor in the 11th century who performed miracles and is popularly worshipped among the southern Chinese. The right is Saintly Emperor Guan (關聖帝君 Guān Shèng Dì Jūn). This is Guān Yǔ (關羽), the Three Kingdoms Period general who is so revered in the Chinese sphere of influence. The martial god is known as a god of war, but also as a protector and symbol of loyalty.

During the 1998 restoration of the temple, a scroll was discovered in one of the high beams of the hall. A 1907 gift from Guangxu Emperor (光緒帝 Guāngxù Dì) of the Ming Dynasty, it reads ‘Gentle Waves over the South Seas’. While the reason it was hidden remains unclear, it is clear evidence of the temple’s status. The scroll may more likely have been a gift of the Empress Dowager Cixi (慈禧太后 Cíxǐ Tàihòu), the real power behind the throne. The mighty woman wanted to generate support from conservatives to ensure her continued power. As Singapore had both conservatives and reformists in Singapore, the scroll served to help her cause.

After a few moments with the goddess, you walk back into the courtyard and out through a gate into the courtyard that runs along the left side of the temple complex. Above the roof of the hall ahead of you, you see the mirror pagoda to the Keng Teck Huay Pagoda. This, the Chung Wen Pagoda, sits in another small complex that mimics that of the soon to be Temple of the Heavenly Jade Emperor. Added in 1849, along with the Chong Boon Gate, the small complex, which is unfortunately locked, held the oldest Chinese school in Singapore. The Chong-Wen Ge (Institute for Veneration of Literature) was supplemented with the Chong Hock Pavilion as a girls’ school in 1915. Ruing the fact that you cannot enter, you instead occupy yourself with the hall immediately ahead of you.

The hall that is closest to the sea holds the statue of Cheng Huang Ye (城隍 Chénghuáng), the city god. Each city has a city god and they are responsible for the defences of the city. Cheng Huang Ye also has a magistrate-type role and ensures that people behave correctly. On either side of the city god are two fearsome looking figures. The Two Great Generals (大二爺伯 Dà Èr Yé Bó) are usually found next to the Cheng Huang. They are two generals named Qī Yé (七爺) and Bā Yé (八爺) who are responsible for escorting spirits to hell to be judged. Sometimes part of a group of eight, their names translate as Seventh Lord and Eighth Lord. General Fan is known as being stern and has the role of Arresting Lord; namely bring the wicked spirits to hell. Another name that he has is Fàn Wú Jiù (范無咎), meaning ‘no mercy if arrested’. This short black faced figure stands to the left of the city god and holds a tablet that states ‘arrest the evil’. On the right is General Xie, a tall, white faced being with a long lolling tongue. The Catching Lord is responsible for bringing good spirits for judgement and he carries a fan that says “see and smile” (見笑 jiàn xiào), while his hat says “one who sees me will have great luck” (一見大吉 yī jiàn dà jí). His other name is Xiè Bì Ān (謝必安), meaning ‘apologise and you are pardoned’, showing his forgiving nature.

The two generals of hell were originally magistrate officials in the city of Fuzhou in Fujian province. Their story says that one day, they were on their rounds when a storm started brewing. When they reached Nan Tai Bridge, Fan told Xie to go and get umbrellas and meet him back on the bridge. On his way back, Xie got stomach pains and he had to rest. The rains started falling and the river began to flood. Fan stayed put, as he knew Xie would return. Eventually, the river swept him in and, due to his struggling and drowning, his face turned black and he died. When Xie arrived to find his sworn brother dead, he tried to drown himself, but he was too tall, so he hanged himself from a tree and his tongue hung out from his mouth. After their death, they were immortalised as the Black and White Guards of Impermanence (黑白無常 Hēibái Wúcháng).

Moving up to the next hall, you encounter a martial looking deity. This is “Sacred King, Founder of Zhangzhou” (開漳聖王 Kāi Zhāng Shèng Wáng), the first governor of the city of Zhangzhou in Fujian province. In life he was known as Chén Yuán Guāng (陳元光) and was a Tang Dynasty general in the late 7th century. He ruled the new city so well, that when he died, the Hokkien people deified him. Passing the statue, you see that the next hall is filled with ancestor tablets of the founders of the temple and community. The hall on the opposite cloister also contains these tablets. Turning back to the central axis of the temple, you enter a courtyard behind the main temple hall and stand facing the rear hall. Although small, it houses an important trio.

Before inspecting the statues, you look up at the roof beam at the front of the hall. You note some odd looking little figures carved into the woodwork that are holding up the temple roof. These dark skinned and curly haired people represent the Indians who lived in the nearby village of Chulia. These neighbours of the Chinese helped in the construction of the temple and as a reminder of their support and in the spirit of cross-cultural cooperation in Singapore, they were immortalised in the temple structure. Moving into the shade of the roof they support, you view the statues. In the centre is Kuan Yin (觀音 Guānyīn), a Chinese incarnation of Avalokiteśvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. Her role as the Goddess of Mercy, makes her very popular among the Chinese Buddhists. The statue you see before you depicts her with a thousand hands and a thousand eyes so that she can see and aid all those who need her help. The bodhisattva manifests anywhere she is needed. To her left and right are lesser seen deities and your interest is aroused. The female statue to your left is the Queen of the Moon Palace (月宮娘娘 Yuè Gōng Niáng Niang). Known also as the Moonlight Bodhisattva or Moon Goddess (太陰娘娘 Tài Yīn Niáng Niang), she lights the sky at night and fulfils wishes for the common people. As she is normally depicted as a young lady, she is seen as a matchmaker for girls to pray to and a bestower of beauty. On the opposite side of Guānyīn is the Star Lord of the Solar Palace (日宮太陽君 Rì Gōng Tài Yáng Xīng Jūn) or simply, the Sun God (太陽神 Tài Yáng Shén). Also known as the Sunlight Bodhisattva, he patrols the heaven and earth and divided the day and night. His light destroys the darkness and wickedness associated with that. Giving a nod to this world protecting deity, you move on to the cloisters on the right of the temple.

After passing another ancestor tablet hall on your way down, you come to the central hall on the right side. This chamber houses a white bearded statue of Confucius (孔子 Kǒng Zǐ). The ancient teacher was originally an official of the state of Lu during the Spring and Autumn period. He gave up his post to become a teacher and his philosophy and teachings became famous. After his death in 479 BCE, his students compiled the Analects, a book of his sayings that has survived to this day. His message of respect for authority, national pride, wisdom and nobility has always been popular with the ruling classes, but his message of common education and filial piety made him popular with the common people too. Although the temple is not Confucian, his presence here adds to the inclusive nature of Thian Hock Keng.

As you continue towards the front entrance, the final hall of your circuit hails you. Inside, the main statue is Sangharama Bodhisattva (伽藍菩薩 Qiélán Púsà). This is a Buddhist title for the ubiquitous Three Kingdoms Period general Guān Yǔ(關羽). On each side of him are statues of his adopted son, Guān Píng (關平) and his bodyguard, Zhōu Cāng (周倉). Although he is worshipped as a god and ancestor in Taoism and Shenism, his incarnation as Sangharama is that of a temple protection bodhisattva. An ancient Chinese Buddhist text tells the story of a Sui Dynasty (581 – 618 CE) monk called Zhìyǐ (智顗) encountered the spirits of Guān Yǔ and Guān Píng. They built a temple for him on Yuquan Mountain in Beijing and listened to the monk preaching. Having converted to Buddhism, Guān Yǔ was ordained and became a protector of temples and monks.

Leaving the hall and coming back to the front entrance, you look up at the ornate roof structures and muse on the temple’s significance. This temple is the most important Chinese temple in Singapore. It has been richly furnished and adorned over the years and has grown along with the Chinese community. It represents the spirit of the immigrant population; not just the Hokkien people, or indeed the Chinese. The Indians of the area also have a connection to the temple and it has a special place in the story of social welfare and care of those who came to a new country to seek out a better life. Walking away from the temple and looking up at the modern towers that have sprung up, you can see this upward mobility of migrant people in action and at its heart, a low lying, but grand temple that ties the community together.

[…] write a few different types of article for The Temple Trail. Much of it is long form journalism. I have also posted photo journalism pieces and created fully interactive digital maps. I […]