The dusty city of Luoyang in China’s Henan Province does little to inspire a sense of history at first glance. The functional grim architecture is very much of the new China. The hastily constructed blocks appear hazy in the dust cloud that penetrates the crevices of this industrial city. First impressions can be deceptive and Luoyang is such a place. Located on the central plain of China, it is one of the cradles of Chinese civilisation. Along with Beijing, Nanjing and Xi’an, it is one of the Four Great Ancient Capitals of China. If you scratch the surface of this otherwise unremarkable city, you find amazing treasures of ancient times. Founded by the legendary Duke of Zhou (周公 Zhōu Gōng) of the Zhou Dynasty as Chengzhou in 1136 BCE, the city contains relics from many subsequent dynasties. Marvels such as the Three Kingdoms Period Guanlin Temple and the Long Men Grottoes from the Northern Wei Dynasty form the cultural landscape. In 166 CE, an emissary of Marcus Aurelius arrived in the city, but the place you are speeding towards saw a more influential arrival a century before the Roman came.

The taxi driver takes your fare and cheerily, but roughly, gestures the way for you to go. Heading through a relatively nondescript ceremonial archway (牌坊 páifāng), you find yourself in a very powerful space. You are standing on the threshold of the ancient temple that started a spiritual renaissance. White Horse Temple (白馬寺 Báimǎ Sì) is the oldest Buddhist Temple in China: it is where it all began in 68 CE. Considered to be the cradle of Chinese Buddhism, the temple was founded during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25 – 220 CE). It was during the reign of Emperor Ming of Han (漢明帝 Hàn Míng Dì) that Buddhism started to spread though the Chinese lands.

Folk history says that the emperor dreamt of a 12 foot tall golden man who emanated light from his head and that his ministers informed him that the figure in his dream was the Buddha from India. Based on this, Ming sent a group of emissaries to bring Buddhist teachings back to Eastern Han. His group of delegates returned from India three years later with images of the Buddha (one in particular was on white felt), two Indian monks and the Sutra of Forty-two Chapters. Upon their arrival, the emperor housed the two monks in the Ministry of the Grand Herald (鴻臚寺 Hónglú Sì), a government department. Sì (寺) was used to denote a government agency, but when the emperor commissioned the construction of the White Horse Temple in honour of the steed that carried the sutras back to China, he allowed the use of the word in its title. Since then, Buddhist temples in China have always been called sì. The two monks, Dharmaratna (竺法蘭 Zhú Fǎlán) and Kāśyapa Mātaṇga (迦攝摩騰 Jiā Shèmóténg), likely Yuezi people from the Kushan Empire in Afghanistan. They resided in the temple and translated the Sanskrit sutras and writings into Chinese. The first one was the Sutra of Forty-two Chapters (四十二章經 Sìshíèr Zhāng Jīng), followed by the famed Ten Stages Sutra (十地經 Shí Dì Jīng). The prolific work of the two monks attracted many to the temple to be ordained and the White Horse Temple became a grand monastic centre. The temple remained a scholarly centre and many important translations were made there including the Infinite Light Sutra in 258 CE. The temple reached its peak in the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE) during the reign of Empress Wu (武則天 Wǔ Zétiān), the first empress of China, with 1000 monks in residence. It has been destroyed many times over the years, notably during the Huichang Suppression of Buddhism (840 – 846 CE) and the Cultural Revolution of the 20th century, and rebuilt many times as well.

Having passed the modern páifāng, you cross the central of three contemporary bridges that span a pool. You now stand before the main gate to the temple. Here two stone horses gaze at you. Symbolic of the horse that brought the sutras back almost 2000 years ago, they were put here during the Northern Song Dynasty (960 – 1127 CE). The horses have an almost sad countenance. Perhaps they are solemn due to their task, but regardless, they mark the beginning of your journey into the temple proper. What lies ahead of you is based mostly on the Ming Dynasty (1368 -1644 CE) reconstruction and was restored just prior to the visit of the King of Cambodia, Norodom Sihanouk, in 1973. The Cultural Revolution had left the temple ravaged, and the authorities hastily rebuilt the temple to save face. The red entrance gate has some stones from the Eastern Han era, but it has certainly had more than a lick of paint over the years. Stepping through it, you walk into first courtyard of the south to north axis. The main buildings run on this alignment, but standing in the courtyard, you are actually sandwiched by a pair of tombs in the neighbouring east and west courtyards. Hidden by the bell tower and drum tower, they are the final resting place of Zhú Fǎlán and Jiā Shèmóténg. The two founding Indian monks, commanding the respect of all who enter their temple, were interred in round earth mounds with encasing walls. Their presence is as conspicuous as the two white horses and you feel as if you are being observed through the mists of time by the fathers of Chinese Buddhism.

Looking north, you see the first hall on your route, the Yuan Dynasty (1271 – 1368 CE) Hall of the Heavenly Kings (天王殿 Tiān Wáng Diàn). Walking through the door, you are immediately greeted by a statue of the Sack Cloth Monk, Bùdài (布袋), a fat figure that is often called the laughing Buddha. Associated with Maitreya (彌勒佛 Mílèfó), the future Buddha, by Chinese Buddhists, this chubby statue seems a little out of place in the hall. Looking at the figure, you note that he is very small for the size of the hall and you feel that rather than being made for the chamber, he was added prior to King Sihanouk’s visit. The shrine throne he sits in also seems a little too grand for the statue and is from the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1911). Walking around the intricately carved altar and its many dragons, the Four Great Heavenly Kings (四大天王 Sì Dà Tiānwáng) grimace down at you. Also dating from the Qing Dynasty, the clay statues protect the entrance of the temple and the teachings contained inside the complex. Passing these martial figures that line the room, you face the back of the altar and the customary statue of Skanda (韋馱 Wéituó), a dharma protector. The military figure looks out of the rear entrance of the hall and over courtyard that you exit into.

The next building on the axis is the Hall of the Great Buddha (大佛殿 Dà Fó Diàn). Dating from the Ming Dynasty, this is the main hall. You approach the front of the large hall, but are unable to enter. Glancing inside, you see the statues that fill the space. Centrally is a large statue of the Historical Buddha Śakyamuni (释迦牟尼 Shìjiāmóuní). He is accompanied by statues of two of his most important disciples, Mahākāśyapa (摩訶迦葉 Móhējiāshè) and Ānanda (阿難 Ānán). The Hall also has statues of Mañjuśrī (文殊 Wénshū), the bodhisattva of Wisdom, and Samantabhadra (普賢 Pǔxián), the bodhisattva of action. These Ming period statues are wonderful and give the hall a true sense of authenticity. Close by the great altar in the hall is a Ming Dynasty bell that weighs over a ton. The bell is inscribed with ‘the bell resounds up to the Buddha’s Palace and down to astound the ghosts of hell’. This legendary volume is heard when the bell is struck to ring in the New Year. Walking around the outside of the classic Ming-style hall, you look in the back door at the statue of Guānyīn (觀音), the female incarnation of Avalokiteśvara, the bodhisattva of mercy. The serene figure floats in her grotto and looks out with her golden visage upon the next courtyard.

You next come to the Mahavira Hall (大雄殿 Dà Xióng Diàn), which translates to “Hall of the Great Hero”. In Sanskrit, this refers not only to a warrior, but one who has attained high spiritual attainments. The reference is clearly to the figures contained within. Entering the smaller hall, you take a few moments to view the Yuan Dynasty hall. The ceiling has wonderful lotus patterns adorning it. Under this elaborate roof is a magnificent two-storey shine that is covered in carvings of dragons and birds. The enormous shrine is surrounded by 10,000 small wooden Buddha carvings on the walls. The 18 arhats (十八羅漢 shíbā luóhàn), enlightened beings, surround the central figures of the altar. In the middle is Śakyamuni and to the right is Amitabha (阿彌陀佛 Ēmítuófó), the Buddha of Infinite Light. To the left is Bhaiṣajyaguru (藥師佛 Yàoshīfó), the Medicine Buddha. The statues are protected by the heavenly generals Wéituó and Wéilì (韋力). The figures are made of lacquered silk and hemp and date from the Yuan Dynasty. These lightweight statues have lost none of their allure and the sheen shines out from the dark recesses of the altar. Looking out of the back of the hall is Sangharama (Qiélán 伽藍), the Buddhist incarnation of the historical general Guān Yǔ (關羽). Here the Three Kingdoms Period general is a dharma protector and his large frame fills the door frame and imposes his bulk upon you. The figure opposite Wéituó in the hall that is named Wéilì may also be an incarnation of the famed general.

Going out into the courtyard that Qiélán observes, you see well-worn peach-shaped stone on a pedestal. This once sat atop a tower in the temple. The legend states that if you touch it, your diseases disappear. Not wishing to take any chances with your health, you follow suit with the Chinese and emphatically rub the stone. From here, you look northward to the next structure. Ahead of you lies the Hall of Guidance (接引殿 Jiēyǐn Diàn), the smallest hall in the complex. Burnt down in the mid-19th century during reign of the Tongzhi Emperor (同治帝 Tóngzhì Dì), it was restored by his successor the Guangxu Emperor (光緒帝 Guāngxù Dì). The rule of both of these emperors was overshadowed by the real power behind the late Qing Dynasty; the Empress Dowager Cixi (慈禧太后 Cíxǐ Tàihòu). The powerful lady not only exerted power over both her son, Tongzhi, and her nephew, Guangxu, but was also a devout Buddhist. She was a fervent believer in Lamaism (Tibetan Buddhism) and had the family nickname “The Venerable Buddhist” (老佛爺 Lǎo Fóyé). This building restoration would certainly have been part of her merit accumulation.

Stepping up to the diminutive hall, you look into the open doorway. Inside, you see the main figure is Amitābha, the Buddha who resides in the Western Pure Land. As he is able to lead you to his pure land if invoked, he is sometimes known as the Buddha of Guidance. To either side of him are the other two figures of the traditional Amitābha trinity, or the Three Western Saints. To his right is Mahāsthāmaprāpta (大勢至 Dàshìzhì), the Bodhisattva of Moonlight, and to his left Guānyīn, the Bodhisattva of Mercy. The clay statues are from the Qing Dynasty restoration. Not being able to enter the hall, you pace around it and find yourself at the back of the temple before set of stairs that lead upwards.

Ascending the staircase, you end at a brick gateway that leads into the Cool and Clear Terrace (清涼台 Qīngliáng Tái). On the terrace is one of the most important buildings in the temple complex. The Vairocana Pavilion (毘盧閣 Pílú Gé) is named after Vairocana (毘盧遮那佛 Pílúzhēnàfó), one of the five celestial Dhayani Buddhas (五智如来 Wǔzhì Rúlái). As you enter into the raised and walled courtyard preceding the hall, you see a group of monks chanting inside the hall. They are reciting the work that was famously translated here. It was on this terrace that the two Indians translated the Sutra of Forty-two Chapters nearly 2000 years ago. The Pilu Hall itself was built during the Tang Dynasty and the monks sit at a table in front of a seated statue of Vairocana. Either side of him are Mañjuśrī and Samantabhadra. In the presence of these monks who are chanting the sutra in the place of its translation, you are witnessing a tangible part of history. You have a direct line back to those two Indian monks who brought the teachings of the Buddha to China. Having survived many regimes and times of hardship, the dharma itself is irrepressible. Its enemies have been unable to suppress it, even in the dark days of the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution of Emperor Wuzong of Tang (唐武宗 Táng Wǔzōng) and the ravages of the Cultural Revolution. Here, you experience something ancient brought to life.

Stepping back down from the inner sanctum of the temple, you take a few minutes to observe the raised halls on either side of the terrace. These house statues of Zhú Fǎlán and Jiā Shèmóténg, the two Indian monks. Before returning to the front of the temple, you notice a statue of Xuánzàng (玄奘), the legendary travelling monk from the Tang Dynasty. Influenced heavily by stories of the original Indian monks, Xuánzàng at the White Horse Temple, he set out on a 17 year pilgrimage to India from here in 629 CE, an illegal journey under the reign of the Emperor Taizong (唐太宗 Táng Tàizōng). His journey was immortalised in the great fictional novel Journey to the West. He too returned with sutras to a hero’s welcome, but shunned the fame and set to translation. His Chinese versions of the Heart Sutra and the Large Sutra on the Perfection of Wisdom are the standards to this day. Leaving this famous monk behind, you retrace your route, passing yellow robed monks inspecting ancient stelae and past many small side halls and cloisters.

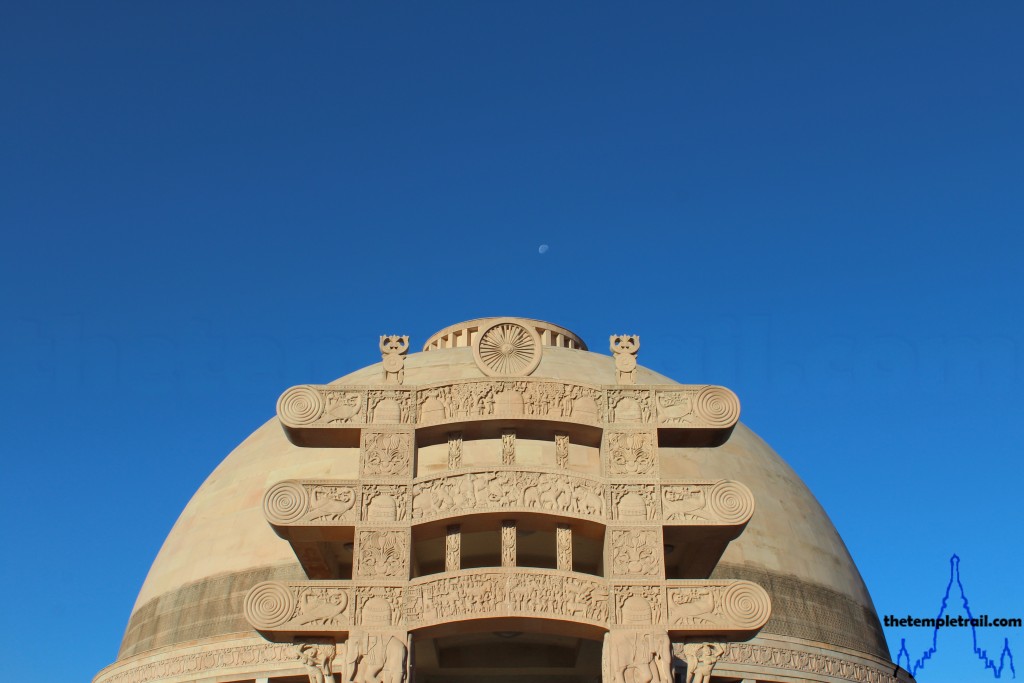

Many halls have been added in recent years too, such as the Hall of the Jade Buddha, the Hall of Changing and the Hall of Six Founders. These newer additions are very small compared with the two huge structures to the east. Exiting the main gate, you make a diversion to the Indian Temple and the Thai Temple. The typical architecture of Thailand can be seen in the enormous structures currently being constructed to the west of the main temple. Next to it, in this ‘international section’, is the Indian temple. Opened in 2010, it is a large replica of the Great Stupa of Sanchi, the oldest stone stupa in India. The building seems a little out of place amid the Chinese halls, but the historical connection between China and India is well marked by this temple, built with the cooperation of the Indian government.

Cutting back across the front of the main temple, you come back to the older sections. Going through a lovely garden, you make out a round tomb mound. Known also as the Vine Orchid Tomb, it is the resting place of Dí Rénjié (狄仁傑). The tomb marker in front of the unruly mound states ‘The tomb of Lord Di Renjie, famous chancellor of the Great Tang dynasty’. Dí Rénjié has had a resurgence of popularity recently in movies and on television in China and Hong Kong. He was a two term chancellor of the first empress, Wǔ Zétiān, during her short-lived Zhou Dynasty. When her husband, the Tang emperor Gāozōng (唐高宗 Táng Gāozōng), died in 683 CE, two of her sons ruled for a very short time. In 690, she dissolved the dynasty and became ruler. It was during her 15-year rule that the temple was at its largest. It is only fitting, therefore, that the man who tempered her reign of terror with openness, efficiency and moderation is buried here. After his death in 700 CE and the overthrow of the empress five years later, his story takes on a more interesting trajectory. The officials he recommended to the empress to replace him were instrumental in her coup against her in favour of her grandson. Dí Rénjié was credited with the restoration Tang Dynasty posthumously. Whether or not he intended this is unclear, as he was the Empress’ favourite and she mourned his loss. The old politician faded into obscurity, until he was the central character of an anonymous 17th century crime novel, “Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee” (狄公案 Dí Gōng Àn). Since then, he and the other famed character of the genre Bāo Zhěng (包拯), have been part of Chinese popular culture. After a few moments looking his weed-strewn grave, you head off and across a bridge to the final area of the temple grounds.

You pass a large modern Chinese prayer hall called the Hall of Great Strength in English, but labelled the Precious Hall of the Great Hero (大雄寶殿 Dàxióng Bǎodiàn) and through an even more manicured garden space. In the distance you see a tall zig-zag shaped tower. As you draw near, you see more clearly the wonderful brickwork of the Qiyun Pagoda (齊雲塔 Qǐ Yún Tǎ). Built in 1175 to replace the original wooden pagoda that burnt down, the 13-storey structure is Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) replica of a Tang Dynasty-style. The pagoda, also named the “auspicious tower venerating the ashes of a Buddha” (迦舍利塔 jiā shè lì tǎ) has a lot to live up to in its predecessor. The early history of the temple was recorded by the famous writer and translator Yáng Xuànzhī (楊衒之) in his seminal work The Monasteries of Luoyang in 547 CE. It is in this book that we get the first account of the Indian monk and founder of Zen Buddhism, Bodhidharma, (菩提達摩 Pútídámó) who Yáng Xuànzhī met in Luoyang in 520 BCE. According to the book, Bodhidharma, upon seeing the original stupa said: ‘Truly this is the work of spirits. I am 150 years old, and I have passed through numerous countries. There is virtually no country I have not visited. But even in India there is nothing comparable to the pure beauty of this monastery. Even the distant Buddha realms lack this’. As you step across the bridge and onto the pagoda’s platform, you notice a strange echo in the air. The structure has an eerie sound quality. It is said that if you stand to the south and clap your hands, the reverberation off the overlapping brick eaves sounds like a frog croaking. Try as you might, your clapping simply echoes without the desired effect.

Leaving the temple grounds and going back out to the dusty road, you feel like you have touched a piece of history. You have made a connection with the past that has a strong foothold in the present. There is almost too much history at the White Horse Temple. It is overwhelming. The great figures from ancient Chinese Buddhist history all had part to play in the drama that unfolded before your eyes. It is a cultural powerhouse that has survived many attempts at its destruction. It remains very much alive and vibrant, full of history, yet rooted in the present.

Wat Phra Phutthabat

Wat Phra Phutthabat