The rain comes down in a light, but penetrating drizzle as you wander through the streets of Taiwan’s capital city. Taipei feels a little run down and as you enter a covered market street, the dank walls do little to challenge that perception. Weaving through small vegetable stands, you break out back into the rain. The aluminium sky covers the heavens and the clouds, while light, are unyielding. Soon you pass some stalls selling traditional medicinal plants, the fresh greens are not only in contrast to the grey surroundings, but also to the traditional medicine of mainland China, where they tend to be dried. Turning a corner you walk a few short steps further to the main entrance to the object of your quest. The turbid heavens seem not to have dampened the spirits of the faithful. The Lungshan Temple of Manka swells with people and as you ready yourself to join the seething masses, you feel the vibrations rebounding from its walls.

Also known as the Mengjia Longshan Temple (艋舺龍山寺 měngxiá Lóngshān Sì), the sanctuary is one of the most important temples in Taiwan and the oldest in Taipei. Dedicated to various entities, the main object of worship is Kuan-in (觀音 Guānyīn), the Chinese female aspect of Avalokiteśvara, the bodhisattva of mercy. The temple was founded in the fifth year of the Qing Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1738) by Chinese immigrants from Fukien (Fujian) province. The temple provided spiritually, but also gave the settlers a place to congregate and acted as a guild house and self-defence school. The immigrants hailed from three different counties within Fukien, one of which, Chin-chiang (晉江 Jìnjiāng), was home to the 7th century Lungshan Temple (龍山寺 Lóngshān Sì). Being devoted to their home temple, the settlers wished to recreate their beloved temple. So the branch temple in the Manka district of Taipei was born. The temple has been rebuilt on two occasions; once between 1919 and 1924, under the supervision of Fujianese master temple builder Wang Yi-shun, and then again a few months after an American bombing raid in 1945, when it needed partial reconstruction. While the temple is mostly Buddhist, the inclusive spirit of Chinese religion has seen the addition of other shrines over the years and Taoist deities are also worshipped here. Kuan Kung (關公 Guān Gōng), the god of war, Wen-chang Ti-chun (文昌帝君 Wénchāng Dìjūn), the god of culture and literature and Matzu (媽祖 Māzǔ), the goddess of the sea are all enshrined in Lungshan Temple along with more than a hundred smaller deities in the side and rear halls.

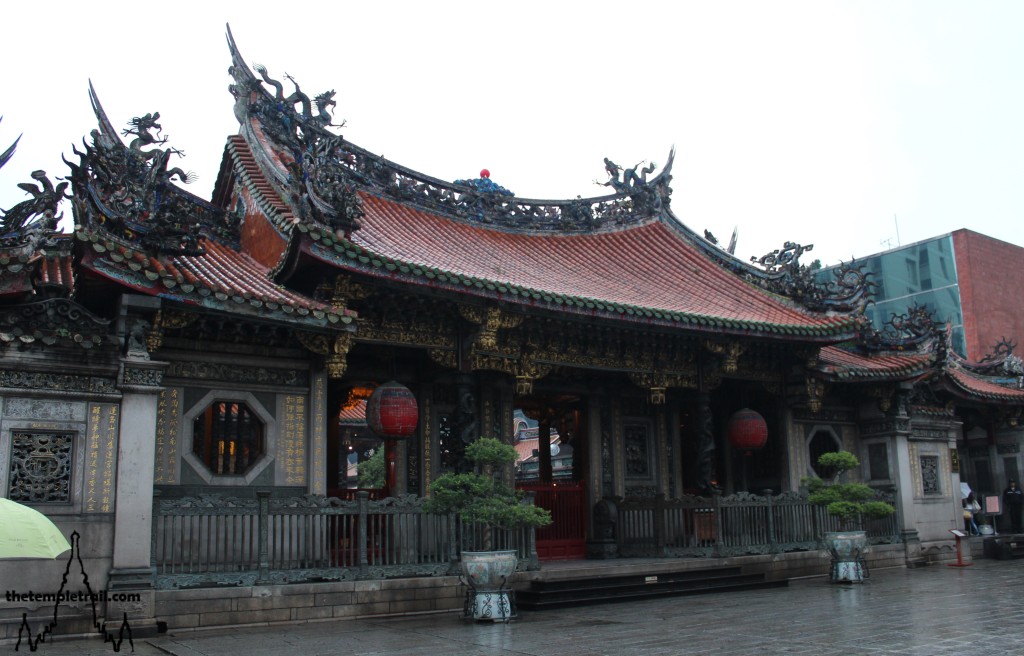

Entering the grounds of the south-facing temple, you find yourself in a water-soaked courtyard. To your right a waterfall adds to the airborne moisture. Before you is an ornate and eye-catching hall. The front hall of the temple is the one built by Wang Yi-shun (王益順 Wáng Yìshùn) in the 1920s. Like the other structures of the temple it has sweeping swallowtail eaves on the roof of red and green tiles. Figures made of jiǎnnián (剪黏), mosaic sculpture made of pieces cut from ceramic bowls, adorn the crest and corners. The beautiful roof is supported by gilded supports that sit atop elaborately carved stone walls of granite and andesite. Poetry is etched into the walls and painted gold. Despite this array of intricacy, the stars of the show are the two black bronze dragon columns that stand before the central portal. These two cast pieces are unique, as there are no other bronze dragon columns in the country. The elaborate hall is used as both an entrance and also a worship space. You use the first of these functions and enter a dark space through the door on the right.

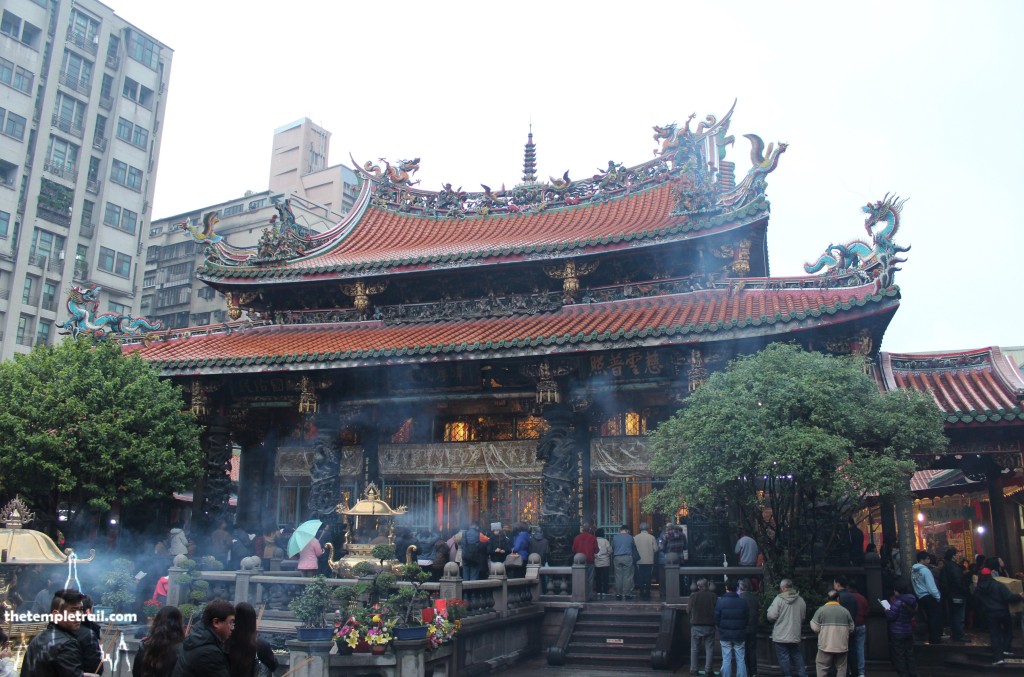

The interior of the hall is open to the main inner courtyard and it is filled to bursting with throngs of worshippers. Gold and black beams and columns are highlighted from the gloom by lights giving the hall a rich aura that gives way to the daylight of the open court. Standing facing the main hall of the temple from the first hall, you have a chance to take in the bigger picture while sheltered from the rain among the chanting masses. The layout was originally a traditional courtyard surrounded by buildings on all four sides (四合院 sìhéyuàn), but was supplemented with an additional hall at the rear. The architect, Wang Yi-shun, designed a far more palatial and substantial structure than the traditional quadrangle. Using stone, timber, porcelain, clay and coloured glass, the temple builders made a masterpiece of Chinese votive architecture. Divided into three subsequent halls with left and right wings, the buildings are jagged with imagery of fantastic creatures that keep vigil over the flocks that come to worship.

Remaining in your vantage point in the centre of the front hall, overlooking the courtyard, you pay attention to the hexagonal towers that rise up out of the left and right galleries. These, respectively, are the drum tower (鼓樓 gǔlóu) and bell tower (鐘樓 zhōnglóu). Jiǎnnián dragons and phoenixes proudly rear up from the corners of the double-eaved roofs. This design of roof was an innovation brought to Taiwan by Wang Yi-shun and is the first example in the country.

Walking out into the courtyard in the light rain, you stand between the two towers. The hypnotic voices chanting in unison make the air vibrate around you as you stand in the centre of the court. Here, one of two large golden incense burners (香爐 xiānglú) is positioned in line with one directly in front of the main hall. These censers are particularly interesting as the posts that support the roof of the braziers are shaped like rotund Europeans. These ‘fools holding up the sky’ or ‘silly barbarians lifting a corner of the temple’ are 18th century designs based on the Dutch. The Dutch East India Company briefly had a colony on the south of the island called Dutch Formosa. The government lasted for a period of 37 years from 1624 until 1662, when the Ming loyalist warlord Koxinga (國姓爺 Guóxìngyé) defeated them. The Dutch themselves had had a turbulent time with the even shorter lived northern Spanish Formosa and with the restless head-hunting aboriginal inhabitants. The ‘silly barbarians’ on the censers indicate the contempt that all of the Chinese people, both local and immigrant, had for the colonial powers at the time.

The main hall sits in the centre of the complex. Turning your gaze to it, you take in the symphonic overture of the grand edifice. The roof is a menagerie of dragons and phoenixes. Mosaic figures ride lions as birds swoop and faces peer out from under the eaves. It is a glorious work of art with small montages and side scenes. It is topped with a small pagoda in the centre of the crest. The crowning roof is joined to the walls without any nails. Climbing the steps you inspect one of the eight carved stone dragon columns. The realistic and graceful carving of the beasts is absorbing. Squeezing through the crowd, you emerge at the central doorway of the hall. Barriers separate you from the nuns and important lay adherents who stand facing the main image of Kuan-in. The golden bodhisattva is surrounded by a flame mandala and various small Buddha and Bodhisattva statues sit in front of her. The image is encased in an elaborate golden altar that also houses her two attendants; Shan-ts’ai T’ung-tzu (善財童子 Shàncái Tóngzǐ – Child of Wealth) and Lung-nü (龍女 Lóngnǚ – Dragon Daughter). Kwan-in herself has survived earthquakes and local strife, but proved particularly resilient during the allied bombing of World War II and the main hall was totally destroyed. When the dust had settled, the golden statue remained unscathed in the centre of the rubble.

Slipping to left of the central entrance you peer in at the statue of the wisdom bodhisattva Mañjuśrī (文殊師利菩薩 Wénshūshīlì Púsà) and then going to the right, that of Samantabhadra (普賢菩薩 Pǔxián Púsà), the action bodhisattva. The hall is filled with a golden brilliance and the visages of the 18 lóhàn (十八羅漢 Shíbā Luóhàn). Better known as arhats, they are disciples of the Buddha. From this very Buddhist scene, you journey to the rear hall of the temple and enter into a different realm.

The original rear hall was added after Manka was made an official port for trade port by the Qing government in 1792. Business became very good and before the turn of the century, the now wealthy Chuan Chiao merchant guild of Manka added the hall to house their patron goddess Matzu. By enshrining the goddess here, they were guaranteeing safe seafaring to the mainland to conduct their business. Soon after, other gods found homes here in the rear of the temple. Going first to the hall in the far left of the temple, you see the first of these gods. While the array is quite dizzying, the halls house three main gods. The right hand side is reserved for Kuan Kung, the god of war. The Three Kingdoms Period general of the state of Shu has been revered by Chinese people for almost two thousand years. His red-faced bearded grimace is iconic and he can be found in thousands of temples all over the Chinese sphere of influence. Aside from being the war god, he is also patron of police, gangsters and business deals. Leaving him, you spot a small shrine to the Old Man Under the Moon, Yue Lao (月下老人 Yuè Xià Lǎorén), known also as The Matchmaker. Singles pray to him in the hope of finding their partner.

Walking to the centre, you see an ornate alter that bears the legend “Heavenly Holy Mother” (天上聖母 Tiānshàng Shèngmǔ). You are standing before Matzu. The Fujian native goddess is very popular all over the South China region and has many names. The tiny region of Hong Kong, where she is known as Tin Hau, alone has 90 temples to her. Anywhere that Fujian natives, particularly the Hakka people went, they took their goddess with them. In her gold-panelled altar, framed by votive lights in towers, she looks peaceful and benevolent. You take a brief break to stand in her company a while. To either side of her, the guardian demons Thousand Mile Eyes (千裡眼 Qiānlǐ Yǎn) and Favourable Wind Ears (順風耳 Shùnfēng Ěr) are contained within their own glass cases. Despite being contained, the two fierce looking companions look as if they would burst out at a moment’s perceived threat to Matzu.

The last section on the right is your next stop and here you find Wen-chang Ti-chun, the god of culture and literature. While quiet at the moment, this section of the temple picks up during exam time when students come to pray for good scores. During the time of the emperors, students took the Imperial Examination (科舉 kējǔ) to qualify as a mandarin (官 guān). If they became a bureaucrat scholar, they would have a position of power. For this reason, the wealthy merchant class installed the god here so that their sons would be successful in the kējǔ and have a chance to wield real influence. In the very far corner of the right of the chamber is the shrine of an interesting little god. Impish in appearance, K’uei Hsing (魁星 Kuí Xīng) is an attendant to Wen-Chang, but he is also specifically the god of examinations. It is this little figure that students must really placate in order to score well. Associated with the plough constellation, he stands on the back of a turtle to represent coming first in the kējǔ.

Having no exams to take, you leave him and look back at the rear hall and its abundance of gods. Many of these are transfers from demolished temples. When Taipei was expanding, many temples were torn down to make room for new streets. The displaced gods were given a home here in Lungshan. Meandering back through the grounds, chanting is still reverberating off all of the surfaces. The temple is not only active, but extremely popular. Perhaps it is to do with the seemingly indestructible nature of the Kwan-in statue, or possibly the heritage of the temple. Maybe is because so many gods are represented here, or that it is such an iconic place. Regardless, the power the beautiful temple has over people is more than evident. The space never gets emptier and as you leave, more are coming in, while few are leaving. Not even the constant drizzle seems to dampen their spirits.

Dhammayangyi Pahto

Dhammayangyi Pahto