When visiting Southeast Asia, you will find a dazzling assortment of different religious buildings. None are more iconic than the Buddhist stupas built to hold relics. While the most famous places for these structures are Thailand, Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia, they can also be found in Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Stupas trace their history back to pre-Buddhist burial mounds, but they came into their own and developed after the passing of the Buddha, whose remains were buried in ten mounds. Later, more permanent structures started to be built to house relics such as the 3rd century BCE Great Stupa at Sanchi in India. The original meaning was retained and the Sanskrit word stūpa literally means heap. While the original purpose was to hold relics, some are built to commemorate events, or as simply votive or symbolic structures.

The Burmese, Thai, Khmer and Lao all have styles that come as a result of the transmission of Theravāda Buddhism from Sri Lanka. One of the most common style of chedi in Thailand is the Lanka-style bell chedi. Interestingly, this bell shape is not much seen in Sri Lanka, where the original round Sanchi-style stupa remains the most usual. The transmission of Buddhism to Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam was of the Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions that came south from China. The Vietnamese stupas are very much influenced by Chinese pagodas, as are the modern Malay ones, due to the Chinese immigrant community. Those of early Indonesia have a more Southeast Asian style and are probably influenced by the Khmers and Hinduism.

Myanmar – Zedi

In Myanmar, there is a clear progression of styles. The earliest stupas were built by the Pyu people and this Pyu-style can be found at the 7th century Bawbawgyi Pagoda at the ancient city of Sri Ksetra near modern day Pyay.

This bulbous, but elongated version of the simple mound is the beginning of the Burmese stupa. In the kingdom of Bagan, this Pyu-style turned into the gourd-shape evident in the Buphaya in Bagan.

Bagan is home to many great stupas which illustrate the stupa’s evolution in Myanmar. The wonderful, 11th century Shwezigon Pagoda pioneered the banana bud design and the beginning of elongation.

By the 12th century, the bell-shape of the golden Dhammayazika Pagoda, also in Bagan, came to be the standard.

The stunningly beautiful Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon is the culmination of centuries of Burmese architectural innovation. Expanded many times by various rulers, the Shwedagon has elements of the bell shape, the banana bud, upturned and down-turned lotus petals, a turban and a diamond bud, topped with a hti (umbrella). It is the zenith of grace in stupa design.

Laos – That

Laos has a unique style of stupa which stands out from those in neighbouring countries. Vientiane has the best example of the Lao-style that: Pha That Luang. This is considered to be a national treasure of Laos. It is tall and thin with a curvilinear design. It has four corners and is modelled on an unopened lotus bud.

This style is also evident, in much smaller form, in That Chom Si in Luang Prabang. The slim angular lotus sits atop Phou Si hill in the centre of the town.

In Vientiane, That Dam, displays a different style. This shows some influence of its southern neighbour, Thailand, but retains an angular nature, rather than having a round ‘bell’.

Luang Prabang has one quite unusual stupa that seems more closely linked to the Sri Lankan mound shape. Known as the ‘Watermelon Stupa’, That Pathum (or That Makmo) at Wat Wisunalat is a 16th century Singhalese-style stupa and a one-of-a-kind in Laos.

Thailand – Chedi

Thailand gets the prize for the most varied styles of stupas. While many associate the Khmer-style prang with Thailand, it really isn’t a true stupa like the chedi. The famed ‘corn cob’ shape actually developed from Khmer temples and not from burial mounds. While they did evolve to have the same relic containing function, they are not quite stupas, as you can normally enter them.

Many great examples of towering prangs are found in the old capital of Siam, Ayutthaya. A walk around the ancient city will reveal many kinds of chedi also. The most famous is the Ayutthaya-style chedi, which you can find in temples like Wat Chai Watthanaram. It is a stylized, squarer version of the bell chedi and has 12 indented corners.

In the northern city of Chiang Mai, you can find a wonderful example of a chedi in the heart of the ancient Kingdom of Lanna. The golden stupa at Wat Phra Doi Suthep is again a variation of the bell chedi, but is in the Lanna-style with its multiple facets and tiers.

Chiang Mai is in itself like a museum to the chedi and you can find incredible variations. Wat Jedyod (Chet Yot) has a unique seven spired chedi that gives the temple its name. The stupa was built in 1455 and once has a Bodhi tree growing out of it and was inspired by the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya.

Another unusual chedi in Chiang Mai is the circular tired one at Wat Phuak Hong. The 16th or 17th century stupa is mysterious and was either influenced by Yunnanese votive structures or is a circular version of the Mon Haripunjaya-style chedi.

As Lanna was once a vassal of Burma, there are a number of Burmese temples in Chiang Mai. One of the most interesting is Wat Ku Tao and its unusual bulbous stupa. The chedi, built in 1613, is based on five melons stacked one on top of the other and contains the remains of Tharawadi Min, son of the famed Burmese conqueror King Bayinnaung.

In nearby Lamphun, just 25 kilometres from Chiang Mai, Wat Phra That Hariphunchai has a special chedi. The former Mon Kingdom of Hariphunchai had its own style before it was invaded by neighbouring Lanna in the 13th century. The Haripunjaya-style chedi, Chedi Suwanna, is square and angular and looks more like an elongated pyramid. There is also a similar one in the town at Wat Ku Kut.

Travelling south to the original Thai Kingdom of Sukhothai you find another Mon Haripunjaya-style chedi at Wat Mahathat, but it is one of many different types of stupa, that surround the main Thanan-style chedi. This is a tall, thin lotus bud that is distinctively from Sukhothai and it can only be there and in its subordinate cities. Was Mahathat has so many different styles of chedi, that it is like visiting an outdoor reference book.

In the capital, Bangkok, you will find many kinds of chedi, but it is a city that is home to many of the classic bell-shaped chedi that people picture when they think of Thai temples. While there are many examples, the golden chedi at Wat Saket Ratcha Wora Maha Wihan on the Golden Mount is a beacon that sparkles in the sun above the Bangkok skyline.

Cambodia – Chedey

The Khmer people of Cambodia have a long history of building temples. During the days of the Kingdom of Angkor, the state religion flip-flopped between Hinduism and Mahāyāna Buddhism, a direct consequence of it once being a vassal of the Śailēndra Kingdom of Java, before its own rise to dominance. In the 13th century the Theravāda tradition has became the dominant form of Buddhism and more recent Cambodian chedey borrow much from those in Thailand and Laos.

The traditional towers of the Angkor Kingdom are of direct descent from the Hindu temples of India, with a Khmer styling, but are not stupas, as they function as temples you can enter. Those at Banteay Srei, a Hindu temple, typify this style. The chedey of 17th to 19th century Cambodia are very similar to those in Thailand. The royal stupas at Oudong, to the north of Phnom Penh are prime examples of these. They are much like the Thai bell-shaped chedi and Ayutthaya-style, but are somewhat elongated. The Ang Duong Chedey, which holds the remains of King Ang Duong, was built in 1859 and typifies the Khmer version of the stupa.

Vietnam – Phù đồ

The Chinese influence on the stupas of Vietnam is palpable. The tower-like structures, normally holding the remains of monks can be found throughout the Buddhist temples of the country. Known as Phù đồ, they are like pagodas found in China. While there are native towers in Vietnam, these tháp were built as Hindu temples in the Kingdom of Champa. Similar to the Khmer towers of Cambodia, these towers are not stupas, but highly iconic.

The most common stupas are stout and square and can be found dotted around Buddhist temples. These often have Chữ nôm (Sino-Vietnamese characters) emblazoned on them. These are repositories for the remains of monks and are commonplace in most monasteries.

In Hanoi, there is one particularly interesting stupa called the bảo tháp lục độ đài sen (Lotus Stupa) at the picturesque 17th century Thiền (Zen) Buddhist temple, Chùa Trấn Quốc. The stupa is 11 storeys tall with an additional nine storey finial. The niches of the stupa hold white statues of Amitābha Buddha and the design is distinctly Chinese.

In the central Vietnamese city of Hue is the Thiên Mụ Pagoda. Built in 1601 the seven storey pagoda is named after a local folk figure. Thiên Mụ,the Celestial Lady, sat at the site and predicted the coming of a lord who would build a pagoda there in the future. Upon hearing this legend, Lord Nguyễn Hoàng ordered the stupa built. The octagonal tower is influenced by China, with a Vietnamese aesthetic.

Malaysia and Indonesia – Candi

Historically linked, Malaysia and Indonesia are relatively modern constructs as far a countries go. The Melayu Kingdom consisted of Malaysia and Sumatra until the mid-7th century, the Medang Kingdom occupied central Java from the mid-8th to early 11th century, and the Śrīvijaya Kingdom dominated the whole region from the mid-7th to mid-14th century. There are a vast array of Buddhist temples in the region, despite it being a minority religion.

Malaysia is lacking in ancient stupas, but has a large number of more modern Chinese temples, reflecting the immigration trends of the 19th century. The standout stupa is the Pagoda of Rama VI in Kek Lok Si, Penang. The Chinese temple’s stupa is named after King Rama VI of Thailand who laid the foundation stone. It is a composite ‘pagoda’ with Chinese, Thai and Burmese sections designed to teach that sectarianism is not necessary.

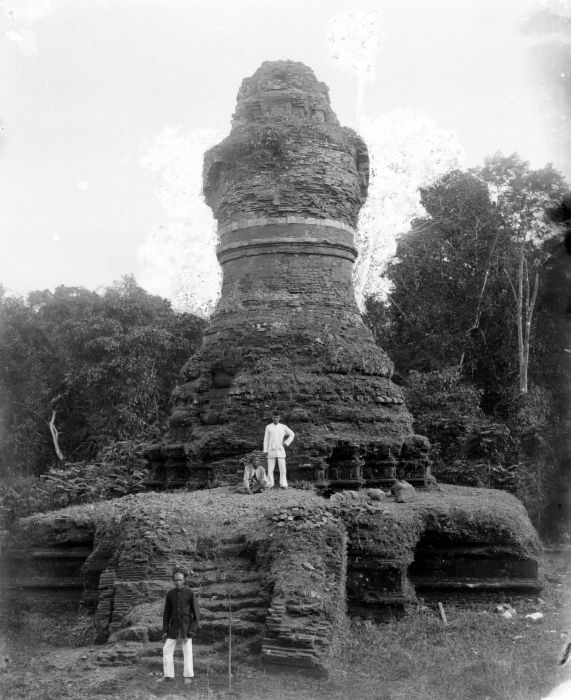

In Sumatra, a predominately Muslim island like neighbouring Java, has a few hidden gems. Ruins from the Melayu and Śrīvijaya eras, the temple complex of Muaro Jambi contains several Buddhist candi (temples and stupas). Muara Takus, another Buddhist complex of the same era contains the lotus-shaped Candi Mahligai, a stupa that is unique in Indonesia.

Java has several Buddhist ruins, mostly in the central and eastern regions. The largest concentration are around the city of Yogyakarta, once the seat of the powerful Medang Kingdom of the Śailēndra dynasty, a family who also ruled the Śrīvijaya Kingdom. The family were Mahayana Buddhists with some Hindu members, leading to them building both kinds of temple. Two major Buddhist sites are Candi Plaosan that was surrounded with hundreds of small stupas and Candi Sewu which also had a mandala pattern of stupas around the main building.

The major stupa of the area is the incredibly famous Borobudur. The largest Buddhist monument in the world is a stupa in its own right while having a collection of stupas on its summit. A mandala design, the vast structure is designed to take pilgrims through the Buddhist cosmos as they slowly scale the stupa up to the peak. The step pyramid style structure was built in the 9th century and took around 75 years to complete. It was abandoned at the beginning of the 11th century when the Medang capital moved to East Java. The impressive edifice is justifiably one of the most famous in the world.

Southeast Asia is a treasure trove of Buddhist stupas. While they can be found all over the world, there is nowhere else with quite such diversity and cultural multiplicity. The devotional buildings are monuments to the faith of the people, the power of the rulers and the grandeur of the kingdoms of the region. When visiting the countries of Southeast Asia, it is worth paying attention to these fantastic edifices. They are testament to the rich cultural and religious wealth that can be found in that exotic corner of the world.

Monumental in Death

Monumental in Death