The driver of your hired car occasionally turns around to pass comment in Mandarin, stretching your limited knowledge to its limits each time. His bite-sized chunks of amiable conversation keep him entertained on an otherwise run of the mill journey for him. The 25 or so kilometres that you have travelled from the city of Qufu in Shandong Province seem longer than that, as the countryside appears unchanging out of the windows of the European car. The city you have left is famous for the Temple of Confucius, as it was the Perennial First Teacher’s hometown. Having seen all it has to offer, you are now slowly making your way down dusty highways to the neighbouring town of Zoucheng, to the south. Pulling up in a car park in the small Chinese town, your driver jumps out and guides you in the direction of what you have come for. He tells you that he will stay here and you know that you will find him sleeping in the back seat upon your return. Before you, the ceremonial gates of the temple that honours the Perennial Second Teacher stand proudly. This is Mèng Miào (孟廟), the Temple of Mencius.

Mencius (孟子 Mèngzǐ) was born in the State of Zou (now Zoucheng city) in 372 BC during the Warring States period (403 – 221 BCE). Raised by his mother only, he is the most famous Confucian after Confucius (孔子 Kǒng Zǐ). His given name was Mèng Kē (孟軻) and he was a student of Zǐsī (子思), Confucius’ grandson. Mencius eventually took up a position at the Jixia Academy (稷下學宮 Jìxià Xuégōng) in the State of Qi, the most famous academy of the time. He took leave from his position for three years following his mother’s death, so that he could observe the proper period of mourning. He roamed throughout China, like his predecessor Confucius, trying to affect changes in the ruling classes. Eventually, disheartened by his inability to convince the lords to embrace Confucian philosophy, he retired from public life.

He died aged 83 and left a legacy that lived on through his eponymous major work, the Mencius. Posthumously, he has been venerated by various rulers of China, but did not receive his first title until one was conferred in the 11th century CE by Emperor Shenzong of Song (宋神宗 Sòng Shénzōng), more than a thousand years after his death. Perhaps this reluctance to honour him came from his deviation from original Confucian thought regarding the right of the people to overthrow an unjust ruler. Mencius furthered the Theory of Benevolence that Confucius created and evolved it into his Policy of Benevolence. As his work was later amalgamated into the Confucian canon, the theories about state affairs are called the doctrine of Confucius and Mencius.

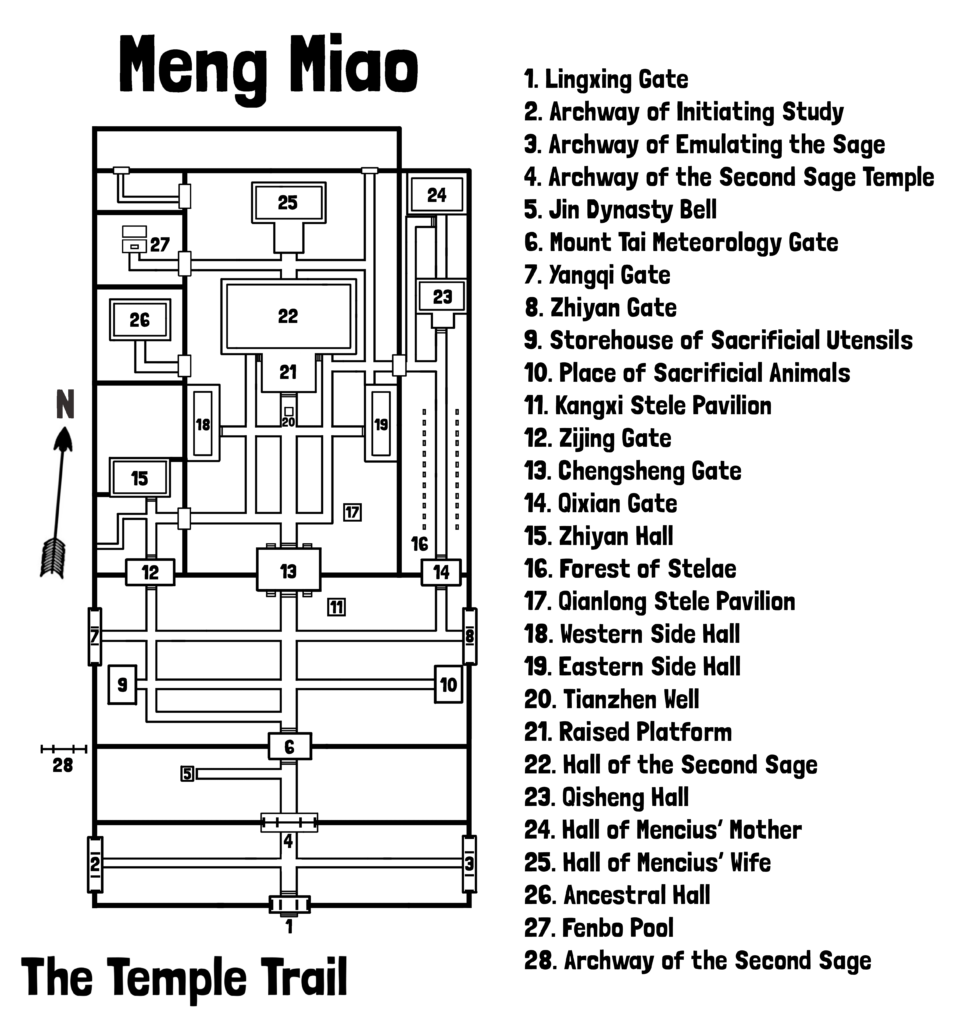

The temple was first built in 1037 CE during the rule of Emperor Renzong of Song (宋仁宗 Sòng Rénzōng). This sudden interest in the Second Sage (亞聖 Yà Shèng) was due to the rise of neo-Confucianism during the Song dynasty (960 – 1279 CE). In 1121, the temple was moved to its current location, away from the tomb of Mencius. The large scale of the temple as it stands today was reached in 1715 under the reign of Emperor Kangxi (康熙帝 Kāngxī Dì) of the Qing dynasty (1644 – 1912 CE). With many buildings, more than 280 stelae and over 300 trees, it is an impressive compound by any standards. Although it took more than 1000 years until the sage was given a temple, it has now stood for almost the same length of time.

Approaching the temple, you see a mass of green beyond the car park. In front of it is a páifāng (memorial arch) gate with its name emblazoned on the front. The Top Scholar Star Gate (櫺星門 Líng Xīng Mén) is striking with its greens and blues and intricate dǒugǒng (斗拱) roof supports. The structure is normal for the area and can be found on other temples, such as the Duke of Zhou Temple and the Kǒng Miào (孔廟) in Qufu. Passing through the first portal, you have now officially entered the sacred space. On the left wall of the courtyard is the Archway of Initiating Study (開來學坊 Kāi Lái Xué Fāng) and on the opposite side is the Archway of Emulating the Sage (繼往聖坊 Jì Wǎng Shèng Fāng ). These two are simple gates, but before you is a more striking stone archway (牌坊 páifāng), the Archway of the Second Sage Temple (亞聖廟坊 Yà Shèng Miào Fāng). This stone entrance style is also typical of Confucian temples and by passing cloud adorned cylindrical columns, you know that you are entering into a temple that reveres a sage of that tradition.

The courtyard contains a bell from the Jin dynasty (265 – 420 CE), but the main feature is the Mount Tai Meteorology Gate (泰山氣象門 Tài Shān Qì Xiàng Mén). Passing rows of banners fluttering in the wind, you approach the rather simple gate. First built by Temür Khan (元成宗 Yuán Chéngzōng), the second emperor of the Yuan dynasty (1271 – 1368 CE) in the early 14th century, the gate underwent significant repairs in the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644 CE). The gate takes its name from a quote by Chéng Hào (程颢), an 11th century neo-Confucian scholar, who said ‘Confucius represents Heaven and Earth, Yánzǐ (顏回 Yán Huí) represents wind and cloud and Mencius represents Mount Tai’. You pass through the shaded area under the gate, which shelters you today from the sun rather than other meteorological elements, and end up in a courtyard with three possible routes ahead.

On either side of you are functional buildings which are closed and only used on ritual occasions, though very rarely these days. On the left is the Storehouse of Sacrificial Utensils (祭器庫 Jì Qì Kù) and to the right is the Place of Sacrificial Animals (省牲所 Shěng Shēng Suǒ). Next to these respectively are the Cultivating Moral Character Gate (養氣門 Yǎng Qì Mén) and the Knowledgeable Speech Gate (知言門 Zhī Yán Mén). Following the central path through the courtyard brings you to the Kāngxī Stele Pavilion. The stele contained within, sits in the back of a stone turtle and was written by the Kāngxī Emperor himself in 1687.

Before you are three gates. In the centre, the largest, is Receive the Sage Gate (承聖門 Chéng Shèng Mén). This gate takes you straight into the main courtyard of the temple, where the principle hall is. The gate was first built in 1121 and renovated in 1496 is a reference to Mencius inheriting the Confucian tradition. To the left is Send Respect Gate (致敬門 Zhì Jìng Mén) and on the right Enlighten the Virtuous One Gate (啟賢門 Qǐ Xián Mén). Rather than going in to the main courtyard, you veer to the right and go through Qǐ Xián Mén. This gate, built in 1496 and repaired in 1836, refers to Mencius’ parents enlightening him.

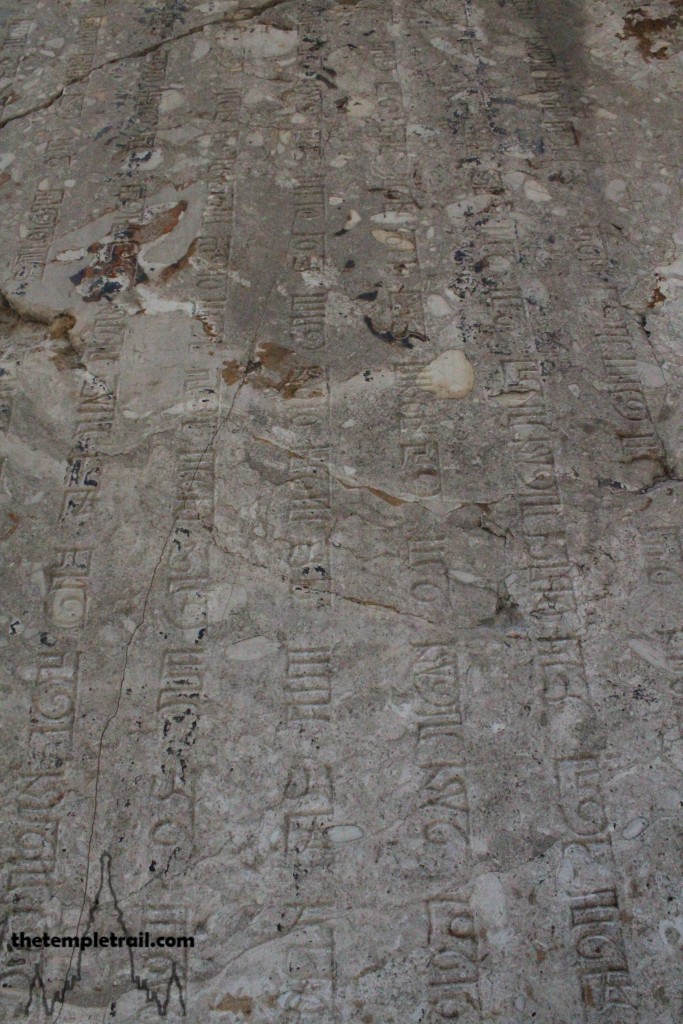

You are greeted by two rows of stelae on the other side of the gate. The impressive stone monoliths are an incredible collection ranging from the Second Sage stele from the Yuan dynasty to Qing dynasty contributions. The Second Sage stele, written in the unusual Phagspa script of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, decrees that Mencius is the Second Sage of the State of Zou. The collection also has the stele from the Song dynasty conferring the title of Duke of the State of Zou on Mencius. Other stelae are dotted around the temple too, including the ‘Five Stelae’ that were rescued from various important locations around the country and now rest near the Kāngxī Stele. These five were gradually relocated to the temple in the 1970s and 80s, as the original buildings they stood in were destroyed by war. They are the ‘Three Moves’, ‘Mencius’ Mother Cuts Cloth’, ‘Zǐsī Wrote the Doctrine of the Mean’, ‘Picture of Zǐsī’ and ‘A Tribute to Zǐsī’. These final three stelae that honour Zǐsī, Mencius’ teacher, were all moved to the temple to protect them during the days of the Cultural Revolution.

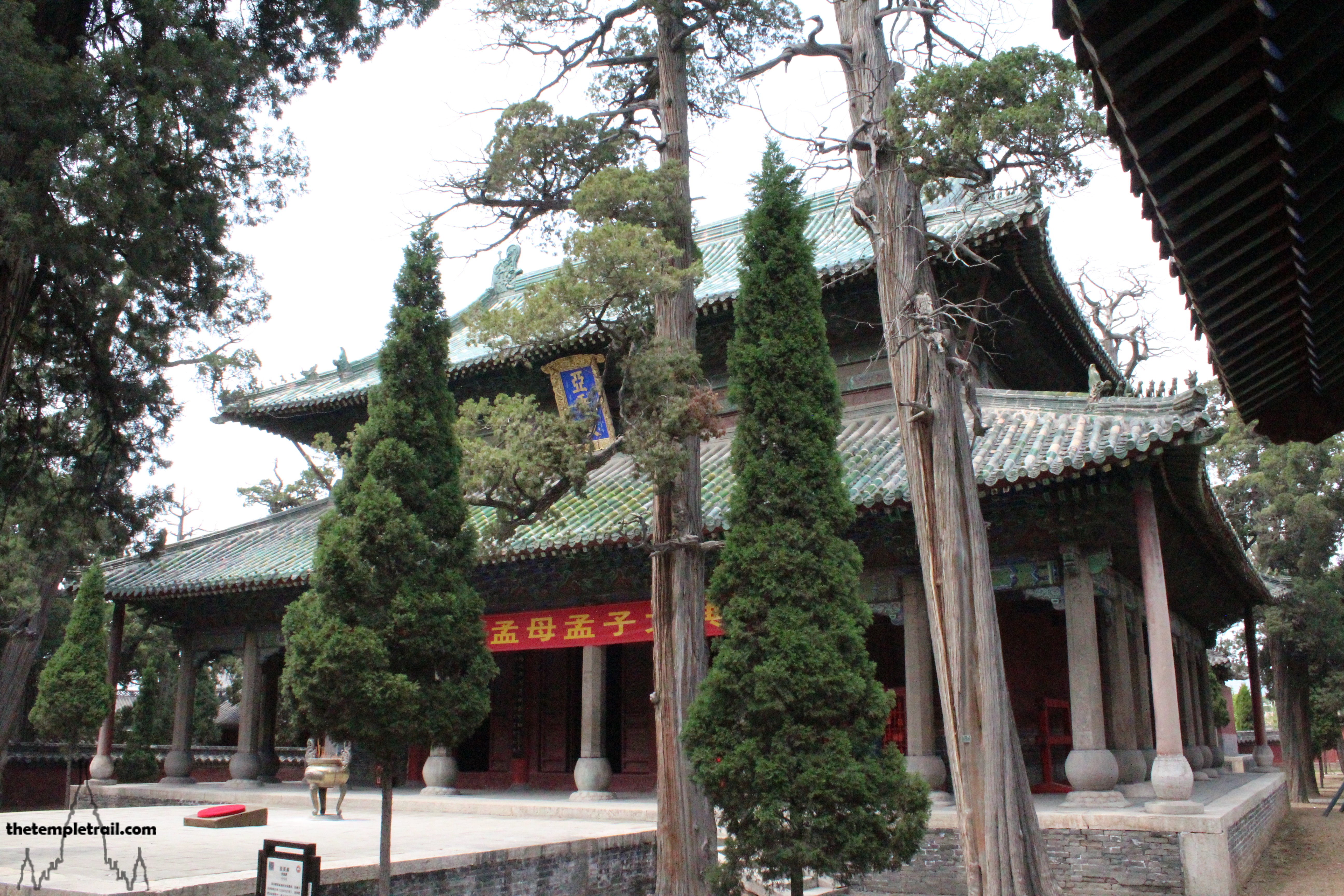

The lines of stelae lead you to the small building called the Enlightened Sage Hall (啟聖殿 Qǐ Shèng Diàn), that sits in the middle of this side courtyard. The diminutive hall is for sacrificing to Mencius’ father. While he died when Mencius was very young and had little impact on his upbringing, in feudal China, paternal filial piety was very important and respect to both of ones parents is a cornerstone of the philosophy. Directly behind the hall is the Enlightened Sage Sleeping Hall (啟聖寢殿 Qǐ Shèng Qǐn Diàn . This is now the Hall of Mencius’ Mother (孟母殿 Mèng Mǔ Diàn), and was built in 1496.

Mencius’ father died when he was very young and his mother raised him alone and in poverty. Her devotion to her son’s education has made her one of the most famous female figures in Chinese history and the idiom ‘Mencius’ mother, three moves’ (孟母三遷 Mèng mǔ sān qiān) illustrates this. It is said that she moved three times to get a proper education for Mencius. First, they lived near a cemetery. Mencius began to mimic the mourners at funerals, so his mother moved them near a market, but he began to take up the cries of the merchants’ sales pitches. The final move took them next to a school. Here, Mencius began to emulate the scholars and study, making his mother happy. In 1316, the title ‘Lady Educator of the State of Zou’ was conferred upon her. Her little hall contains her memorial tablet and you see that people have honoured it with flowers. On the right is a stone statue of a man kneeling and making an offering.

You leave the hall and, taking a side door from the eastern courtyard, you enter into the main central area. Backtracking a little, you move into the middle of the courtyard before you go into the main hall. This courtyard is large and there is much to take in; like the other courtyards in the complex, it is filled with ancient trees that add a tranquillity to the grounds. First you head to the bottom left hand corner to see the Qiánlóng Stele Pavilion. The ‘Tribute to the Second Sage Mencius’ Stele was inscribed by the emperor in 1748. In 1761, he ordered the pavilion built to protect it and at the same time, on built over the stele his father, Kāngxī, inscribed. From here you move to the dead centre of the courtyard and look into the Heavenly Vibration Well (天振井 Tiān Zhèn Jǐng), surrounded by its marble fence.

On either side of you are the West Side Hall (西廡 Xī Wǔ) and the East Side Hall (東廡 Dōng Wǔ). These narrow, long halls one contained the tablets of famous students of Mencius and other great thinkers, but now hold paintings instead. The tablets of scholars such as Yáng Xióng (揚雄) of the Han dynasty and the Tang dynasty neo-Confucian Hán Yù (韓愈) once graced these halls. From the east side, you look into the centre of the green courtyard. The largest building of the set towers over the other structures of the temple. On its marble platform rests the Hall of the Second Sage (亞聖殿 Yà Shèng Diàn), the main hall of the whole compound.

Climbing up onto the elevated platform at the front of the hall, you note the large scale of the ‘stage’. The raised platform (丹墀 dān chí) is a common feature of Confucian temples as it is used as the place to perform ritual music and dance during sacrifice days. You pass an incense censor and stand at the huge doorway to the main hall. The blue and green paint that adorns the beams and brackets supporting the green tile roof has seen better days. The fading colours are in need of a refresh. The double-eaved roof is impressive nonetheless and a feeling of awe strikes you as you prepare to enter into the presence of the Second Sage.

The light from the doorway penetrates the gloom of the hall and as you step inside, the altar holding the statue of Mencius is lit up as if by a spotlight. Looking up to the ceiling that seems so high and far away, you see that each panel is emblazoned with an imperial dragon, highlighting the significance of the sage in Chinese history. Remodelled in 1986, the current hall dates to 1673, when the Kāngxī Emperor did extensive work on the site. In the centre of the hall is the altar to Mencius. The spirit tablet of the Second Sage is placed in front of a statue of him. The image is, unusually, of him as an older man. The most common representation of him is in his middle years, before he withdrew from the public arena. On the eastern wall is a shrine to Lè Zhèng Kè (樂正克), the principle disciple of Mencius. The canopies of the shrines are highly decorated and shelter the two statues in the dusty hall. Stepping from the room and back out into the daylight, you readjust your vision and turn to go further north along the temple axis.

Walking around the back of the main hall, you proceed along the raised pathway and arrive at the Hall of Mencius’ Wife (亞聖寢殿 Yà Shèng Qǐn Diàn). Originally used for worshipping Mencius’s parents, the hall was repurposed during the Yuan dynasty as a hall for the worship of his wife. Leaving this area of the compound, you enter a small enclosure to the west that contains Burn Silk Pool (焚帛池 Fén Bó Chí). This stone basin is in a small walled area within the enclosure and was used as a place to burn offerings to Mencius. Leaving the stone container, you exit back out to the main area and then walk around to the next enclose on the western wing of the temple. This one holds the locked Ancestral Hall (祧主祠 Tiāo Zhǔ Cí). Built during the Yuan dynasty and originally called the Mèng Family Temple, it was repaired in 1483 and again in 1836. More than five generations of the main members of the Mèng family’s spirit tablets are worshipped in the hall.

Back out on the main courtyard, you skirt the Western Side Hall and take a right through to the last of the western segments of the compound. Here you find the Serious Etiquette Hall (致嚴堂 Zhì Yán Táng). Again, this hall is closed, but it was built in 1331, during the Yuan dynasty, the current building dates from 1836. The purpose of the hall is for the descendants of Mencius to purify themselves by bathing and then changing into the ritual garments before beginning the ceremonies of worship. This important consideration undertaken before ancestor veneration is reflected in the name of the hall. The name is a reference to the Classic of Filial Piety (孝經 Xiào Jīng), a Confucian book which is traditionally attributed to a conversation between Confucius and Zēngzǐ (曾子), one of his disciples. Zēngzǐ was the teacher of Zǐsī, who in turn was the teacher of Mencius.

You exit back into the third courtyard of the temple through the Zhìjìng Gate, which was also built during the Ming renovation in 1496 and repaired in 1836. Tracing your steps back through the temple, you feel as if you have walked through a living museum. Next to it is the Mèng family mansion that was used by the family until the communist revolution. Much like the Kǒng family of Confucius, they fled China to escape persecution. The temple is now a showpiece, but the sage is once more being recognised in modern China. While not as popular as the First Sage, Mencius is enjoying a resurgence that is sure to be reflected in increased visits to this temple. For now, you consider yourself lucky that the tree-filled space is relatively quiet and that you were able to freely explore its chambers and courtyards in a more tranquil setting than in the more popular Kǒng Miào of Qufu. Walking back to the car, sure enough, you find the driver sleeping on the back seat. As you approach, a sixth sense kicks in and he springs to alertness, ready to take you to your next destination.

Tin Hau Temple, Causeway Bay

Tin Hau Temple, Causeway Bay