The heat scorches the air you breathe as you step out of Long Ping MTR station in Yuen Long. Not so much a unified town, as a conglomeration of smaller villages, the area seems out of step with the more southern regions of Hong Kong. The air conditioning of the train has not prepared you well for the powerful sun and exposure of the New Territories. Stopping by a 7-11 to pick up some much needed water, you slog along a road that radiates back the heat it has been storing all morning. They say mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun, but you find yourself almost alone out in the midday Hong Kong sun.

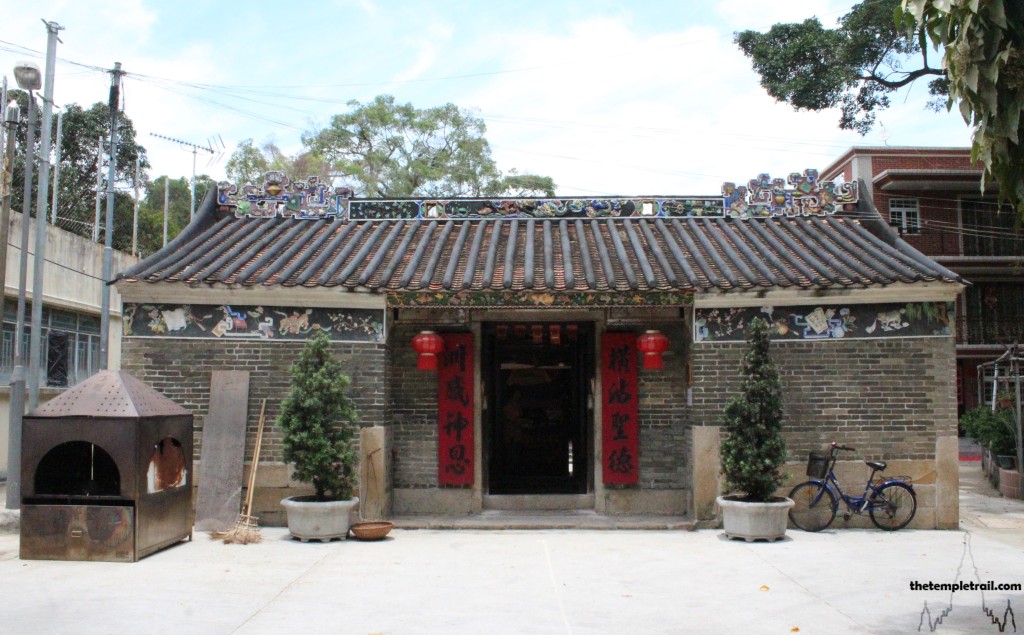

The short walk seems like an epic journey as you turn off the main road and down a smaller street into the village of Chung Sam Wai. As you reach the terminus of the road, the place you have come to see suddenly appears around the corner. The small, but ancient temple is neatly tucked away in the corner of the village, belying its important role in the social life of the area. Unusually, it is dedicated equally to two gods, but is not a Man Mo temple. The building you are gazing at through mirage-like heat waves as Yi Shing Kung (二聖宮 Èr Shèng Gōng), the Two Saint Palace.

Built in 1718 by the residents of six villages in the Wang Chau area, the temple honours the gods Hung Shing (洪聖 Hóng Shèng) and Che Kung (車公 Chē Gōng). The green brick structure is beautifully highlighted with a brightly painted frieze under the eaves of the roof. Auspicious symbols sit in a row all around the building. The tiled roof slopes gently up to an elaborate ridge with angled spiral shapes adorning the left and right. In the centre of the ridge, the motif of carp leaping over the Dragon’s Gate has been used. There is more than one site in China, particularly along the Yellow River, called the Dragon’s Gate. Where the Yellow River passes through a narrow pass in the Longmen Mountains between Shanxi and Shaanxi is particularly famous. The legendary Chinese ruler Dà Yǔ is said to have created the cleft during his flood control measures and it is now called Yu’s Gateway (禹門口 Yǔménkǒu). The story on the roof ridge is that a carp (鯉魚 lǐ yú) that can jump over the waterfall at Dragon’s Gate (龍門 Lóng Mén) is transformed into a dragon. The Famous Chinese proverb “lei yu tiu lung mun” (鯉魚跳龍門 lǐ yú tiào lóng mén), meaning “the carp has leaped through the Dragon’s Gate”, refers to success through hard work and was originally applied exclusively to scholarly pursuits.

At the doorway, you look up at the carved bargeboard. It is brightly painted on a green background and is covered in flowers and floral designs. The two doors are both guarded by door gods that stop evil spirits from entering. On the right is the white-faced Chen Shuk Bo (秦叔寶 Qín Shūbao) and on the left is the gristly black-faced Wat Chi King Tak (尉遲敬德 Yuchi Jìngdé). The two door gods stand silent watch over the temple and even as their beautiful bright paint peels off the door, they look serenely vigilant. Next to each of them, carved onto the stone doorframe, is a small flower-shaped incense holder for joss-sticks.

Entering the building, you stand in the first of the two halls. To your right, a shrine to the door official adds extra security to the temple. A table with an incense brazier on it occupies the centre of the hall which faces out onto the central courtyard. Two ladies who work as the temple keepers greet you enthusiastically in Cantonese. Your obvious lack of language skills does not deter them and the elder of the two picks up a stick and starts pointing things out to you. She directs your attention to the two choi mun that hang above the dong chung spirit doors (擋中 dǎng zhōng). These boat-shaped decorations are common in temples, but these are particularly brightly coloured. The temple keeper shows you that one is adorned with rustic figures of Fuk Luk Sau ( 福祿壽 Fú Lù Shòu) and the other with the Bat Sin (八仙 Bā Xiān), or Eight Immortals. Fuk Luk and Sau are three of the most familiar figures of Chinese spirituality. The three men symbolise prosperity, status and longevity. The Eight Immortals are popular Taoist figures with many stories attributed to them.

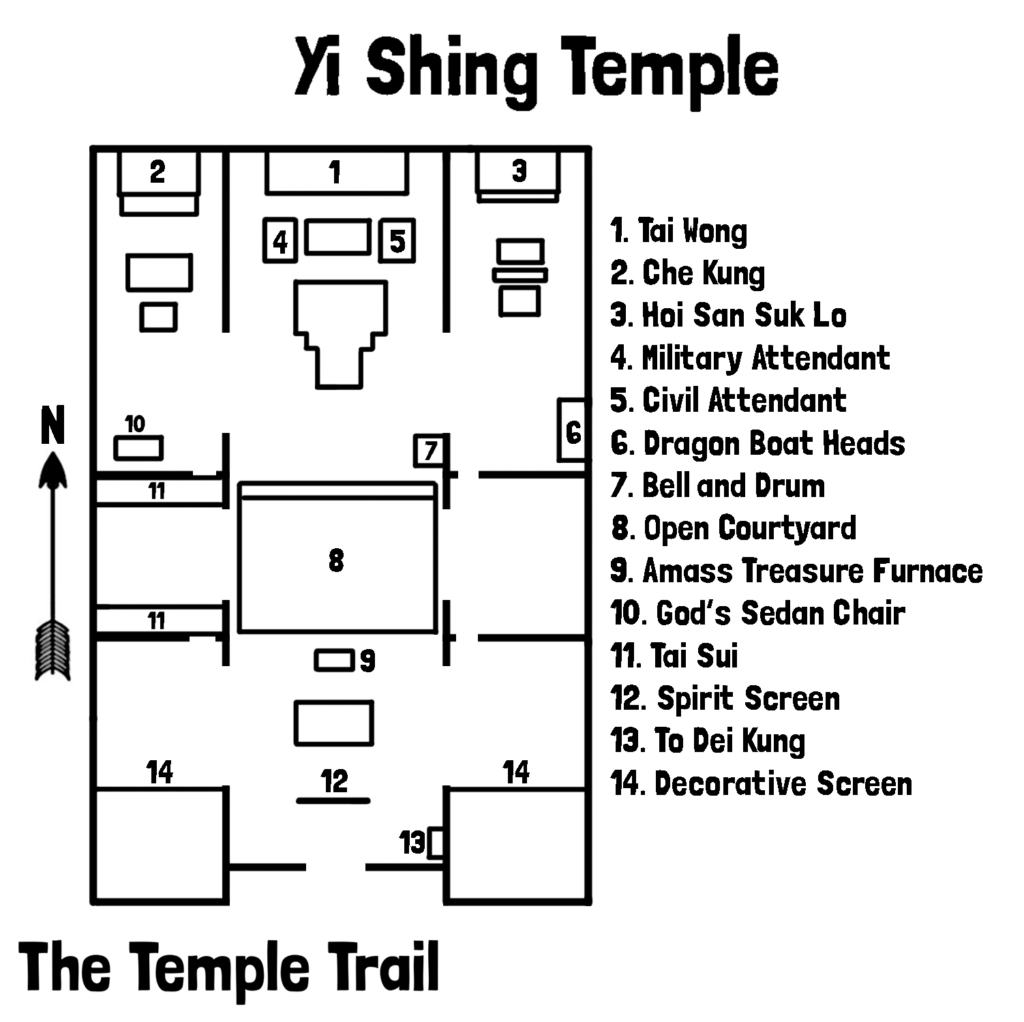

In front of the offering table in the first hall, the old lady draws your attention to an ancient stone incense brazier. The censer has three characters carved into it: jeoi bo lou (聚寶爐 jù bǎo lú) meaning ‘amass treasure furnace’. In Chinese an incense burner is called a hoeng lou (香爐 xiānglú). By placing joss sticks in the censer, you hope to gain wealth. You move on into the courtyard with the temple keeper kind-heartedly, yet incomprehensibly to you, chattering about the various aspects of the temple. You lament your ineptitude in Cantonese and the subsequent missing out on the insights provided by the expert. From the courtyard, you see the main hall ahead of you. To your left and right are side halls. The hall on the right is used as storage, the one on the left used to house the kitchen. The need for a kitchen has now become defunct, even though food is still occasionally needed.

The temple is famous for its Da Jiu (打醮 Dǎ jiào) festival of the Wang Chau area. The Da Jiu is a major festival for ‘worshipping the gods’. The Wang Chau Da Jiu is held every eight years and the food that is eaten is the traditional New Territories ‘poon choi’. Poon choi (盆菜 pén cài) is a meal served in a very large bowl and eaten communally. It has all sorts of meat, seafood and vegetables in it and translates to ‘basin vegetable’ in English. The story of poon choi can be traced back to the last emperor of the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 CE). The child emperor Bing of Song was forced to flee the Mongol invasion of China. When the army of Song arrived in the area, the villagers fed them by emptying out their wash basins and filling them with lots of different cooked items. The tradition of eating this way became ingrained in the culture of the area. The temple kitchen used to provide the poon choi for the festival, but it is now done in the village households.

The former kitchen now houses the Tai Sui (太歲 Tài Suì). These sixty celestial generals take it in turns to govern a year. They are a common sight at any temple in Hong Kong, so the temple keeper glosses over them and you are happy to move onto more unique features. The second hall of the temple holds all of the main gods. Before checking out the central chamber of the hall, you go and look at the one on the right. A circular portal takes you into the room and directly in front of the door is a set of dragon heads used on the local dragon boats. Every area of Hong Kong has a representative team and they are often based out of a temple. The heads are spiritually charged and bestow luck and glory on the boat and its crew.

The altar in the chamber holds two deities. These are the Hoi San Suk Lo (開山宿老 Kāi Shān Xiǔ Lǎo), progenitors of the local area. They are protective gods who provide shelter. The two gods are smoke blackened and their features are hard to distinguish. The interesting and unique feature of this temple can be seen here. All of the gods have a row of miniature versions of themselves in front of them. Here, small bearded figures form a line in front of the altar. The room is quite atmospheric and feeling the presence of the local gods, you exit back into the day-lit open.

Turning your attention to the central section of the hall, you approach the main altar. Behind a row of mini god statues is a dark altar. On either side of it are attendant gods. The military attendant to the left holds a mace, while the civil attendant has a calligraphy brush to keep the books of the main god. Looking out from his palace, Tai Wong’s statue is smoke blackened from years of incense offerings. Tai Wong (大王 Dà Wáng), Great King, is a common name given to the important sea god Hung Shing – Hung the Saint.

In life, his name was Hung Hei (洪熙). He was a government official in present day Guangzhou during the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE). He was so noble and decent in his short life, that the people of the region loved him. He made advances in mathematics, geography and astronomy and founded an observatory to help sailors navigate and predict the weather better. It was these achievements that led to him being deified when he died. He was granted a posthumous title by the Tang emperor: Nam Hoi Gwong Lei Hung Shing Tai Wong (南海廣利洪聖大王 Nán Hǎi Guǎng Lì Hóng Shèng Dà Wáng), meaning ‘Saint King Hung the Widely Beneficial of South Sea’. Said to appear to sailors in need and during sea storms, he is widely worshipped in Hong Kong and the south of China as God of the Southern Sea.

The chamber to the left of the central altar is sealed up, as there is a renovation effort in progress. The cheerful temple keeper ushers you over and she opens the room for you to look inside. Although there is a lot of building material lying around, it is being supervised by the god who resides in the space. With a serious reconstruction of the statue underway, the god and his palace are unadorned. Although work is being carried out on his head, the axe he is holding identifies him to you as Che Kung. Lord Che is a popular god in Hong Kong, despite having few dedicated temples. Here, he is one of the Yi Shing along with Hung Shing.

Che Kung was a general of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127 – 1279 CE) who put down a rebellion and also helped the last two child emperors of the dynasty escape the Mongol invasion of China. After his death, he was worshipped due to his loyalty and fearlessness. He has also come to be a deity who protects people from plague and bestows financial fortune. The chamber is somewhat spartan in its current state, but it normally has, as with all Che Kung altars, a metal pinwheel. The pinwheel is spun in order to for ones wishes to be granted. As the room is in a state of transition, you do not stay too long and you exit out of the circular door. The mini versions of the statue have their own table just outside the portal and the small axe wielding figures act as the substitute for the main image until it is restored.

After trying to exchange a few more words with the temple keepers, you drop a few dollars into the collection box and cast your eye over the temple once more. This shady spot has provided you with more than just shelter from the sun. You have come face to face with gods who are held dear by the locals due either to their connection with the immediate area or to their impact on the people of the region as a whole. You bid farewell to the ladies and brave the sun to journey back to the MTR station and the modern cooling system that keeps it permanently refrigerated. The temple has given you a piece of the old world to carry with you as you return to 21st century Hong Kong.

Shing Wong Temple, Shau Kei Wan

Shing Wong Temple, Shau Kei Wan