All around you high-rises of various ages grow from the ground like a concrete forest. Shabby shop fronts are intermingled with modern chrome and glass fronted businesses. The walk along Queen’s Road East in the Wan Chai district of Hong Kong offers a fusion of not only old and new, but also of East and West. While passing a French bakery, the smell of Chinese medicinal tea lingers in your nostrils. Wan Chai means tiny bay and until a hundred and fifty years ago, the curved road you are traversing was once the shoreline. Over the last century or so and several land reclamations later, the sea is out of sight, obscured by tall buildings.

Your route takes you past a small temple that once sat on the seafront. Hung Shing Temple is built around a large boulder that was originally on the beach. The temple, built in 1847, is dedicated to the God of the Southern Sea, Hung Shing (洪聖 Hóng Shèng). Also known as Tai Wong (大王 Dà Wáng), he was a virtuous Tang dynasty (618 – 907 CE) official called Hung Hei (洪熙). He founded the observatory and his responsibilities lay with, amongst others, sailors and fishermen. He died young and was much missed, so the emperor at the time honoured him with posthumous deification. He is said to have appeared in order to save sailors many times and he is very popular in Hong Kong. Briefly entering this diminutive abode, you see his statue enshrined before the huge boulder that takes up most of the interior. His companions in the hall are Pau Kung (包公 Bāo Gōng), the god of justice and Kam Fa (金花 Jīn Huā), the golden flower goddess. Kam Fa is the most interesting. She was also from the Tang Dynasty and, the daughter of a martial arts instructor, she became a Chinese Robin Hood; stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. She has a role as the patron of pregnant women. Wishing for some luck from the immortals, you pass through the chamber set up for Kwun Yum (觀音 Guānyīn) and Shing Wong (城隍 Chénghuáng), the city god and make your way back out to the road.

You go past the Former Wan Chai Post Office that dates from 1915 and is the culmination of Chinese and European influences on Hong Kong architecture. Soon, you divert up Stone Nullah Lane and by the Blue House, a soon to be renovated listed residential building from the early 20th century. A nullah is a drainage channel that allows floodwater to run off the peaks and away from buildings. The deep stone nullah that the street is named after is no longer visible and is now subterranean. Instead, you pass bric-a-brac shops and mechanic’s workshops before finally arriving at your terminus, the wonderful Pak Tai Temple.

Officially called the Jade Void Palace – Yuk Hui Kung (玉虛宮 Yù Xū Gōng), the Pak Tai Temple is the largest on Hong Kong Island and the biggest Pak Tai temple in the territory. Built in 1863, the temple honours Pak Tai (北帝 Běidì), a powerful martial god. The Barefoot Northern Emperor actually has many names. In Hong Kong he is also called Yuen Tin Sheung Tai (Mysterious Supreme Emperor of Heaven) and Mysterious Warrior (玄武 Xuánwǔ) or Perfected Warrior (真武 Zhēnwǔ) in China. The tale of his origins varies regionally, but in the Hong Kong version he is said to have been a learned Shang Dynasty (1600 – 1046 BCE) prince who was made an immortal by Yuánshǐ Tiānzūn (元始天尊), the Primaeval Taoist Deity. The story tells of his appointment as the commander of the twelve legions of heaven in order to defeat the Demon King. As a result of his victory, he was granted his title and is usually shown in golden armour, stepping barefoot on a black tortoise and snake (servants of the Demon King) to symbolise good defeating evil. The original Chinese story places him in the time of the Yellow Emperor, more than a thousand years earlier. During the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912 CE), his story was romanticised and made more elaborate. Often evoked by martial artists and soldiers, he is a protection deity that will aid with success in battle. He also has the ability to stop natural disasters and is a powerful exorcist. Here in Hong Kong, he has a role as a water god. As the rivers that irrigate the fields flow from the north, he is worshipped by farmers and fishermen to provide a bountiful harvest and a good supply of fresh water.

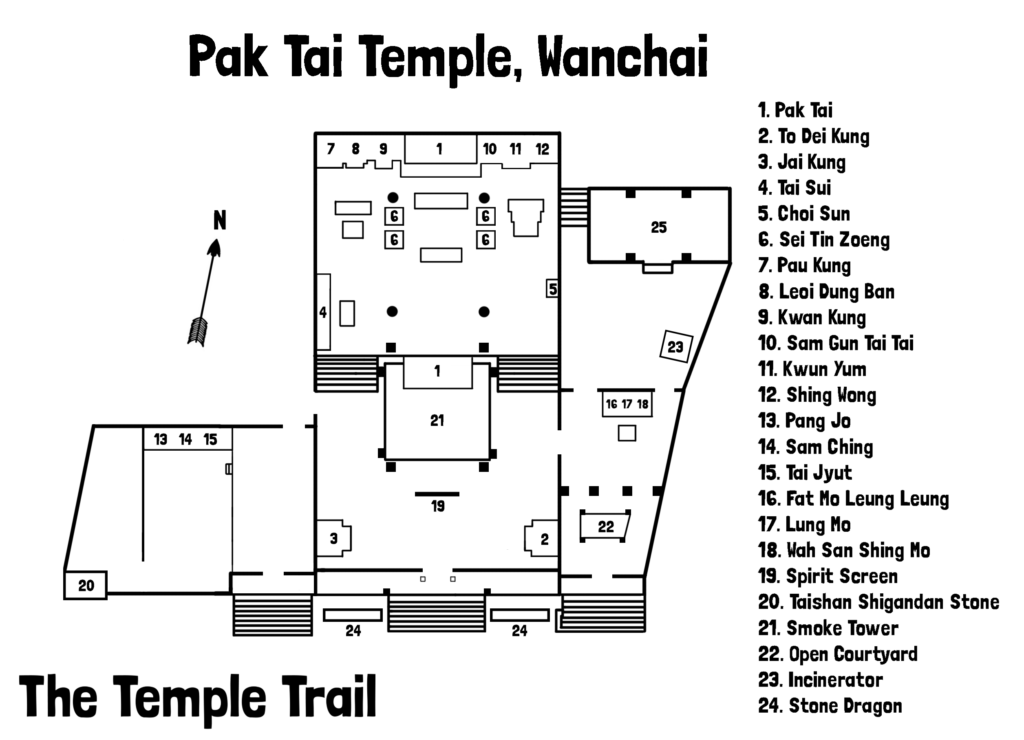

You enter the Jade Void Palace to see the Supreme Emperor of the Dark Heaven. Before crossing the portal to the temple, you find yourself in a banyan filled courtyard. The gnarled ancient trees offer shade and welcome you into the grounds of the palace. A pair of dragons guard the steps and passing their ferocious maws, you look up at the plaque that states name of the temple as Yuk Hui Kung. It was written by a Qing Dynasty military official called Cheung Yuk Tong who was stationed in Kowloon Walled City during the second Opium War against the British. On the roof, a second pair of dragons reside, giving the temple good fortune, prosperity and peace. As soon as you cross the threshold of the temple, you are observed by To Dei Kung (土地公 Tǔ Dì Gōng), the Earth God who occupies the right hand corner of the hall. Immediately ahead of you, through the dong chung (擋中 dǎng zhōng) spirit screen doors, a large bronze statue of Pak Tai locks gazes with you.

The Statue is not originally from this temple. How it came to be here is not clearly known, but it may have been brought from the mainland by the occupying Japanese forces during the Second World War. The image was cast in the 32nd year of reign of Wanli (萬曆 Wàn Lì), the 13th Emperor of the Ming Dynasty. This means that the statue is from 1604, making it almost 260 years older than the building. The statue is fittingly dark, but Pak Tai’s facial expression is not as fierce as one might imagine. He looks at you with a serenely knowing visage. Above the statue are a multitude of brightly coloured lotus lanterns, giving the first chamber a surreal and ethereal atmosphere. The daylight shines into the chamber between the tiers of Shíwān tiles (石灣窯 Shíwān yáo). To your left below the roof gap is a wonderful ceramic scene of a Cantonese opera. The building depicted in the frieze is Lingnan (South China) style and houses detailed little figures. Either side, a pair of birds and a lion bring nature into the motif.

Walking around the large bronze statue, you come to a set of stairs that deliver you to the upper hall. The chamber is the same size as the first, but is filled with imagery of many gods. The room is like a who’s who with small god statues of deities such as Choi Sun (財神 Cái Shén), the god of wealth, Tin Hau (天后 Tiān Hòu), an important sea goddess and Wah Tor (華佗 Huá Tuó), a god of medicine on the altars of the major deities of the temple. Moving to the middle of the chamber, you stand before an array of deities. Occupying the centre of the altars is Pak Tai, and before him are his four soldiers. These four standing figures are the Sei Tin Zoeng (四天將 Sì Tiān Jiàng), The Four Heavenly Generals. These are often linked to the Four Great Heavenly Kings (四大天王 Sì Dà Tiānwáng) of Buddhism. Chinese cultures like to mix the three major religions, so Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism are merged in many places. Many Chinese see them as intrinsically part of each other and part of their culture. As if to reinforce this, you note a statue of Jai Kung (济公 Jì Gōng), the mad Chán Buddhist monk of Hangzhou. In Taoism he is seen as the god of abating distress.

Stepping to the left of the hall, you see the Tai Sui (太歲 Tàisuì). The sixty planetary gods are responsible for the years and the governing general of this year is adorned with a rosette and placed in the middle of the others. Paying your respects to him for a good year, you move to the back wall and the left side of the altars. Before you is Pau Kung, the justice god in his black robes. Next to him is an altar containing two figures. Both statues represent the same character Leoi Dung Ban (呂洞賓 Lǚ Dòngbīn). He is shown seated on a throne and standing. Leoi Dong Ban is one of the Taoist Eight Immortals (八仙 Bāxiān), a group of saintly figures with super powers. Leoi Dong Ban, like the others has several character flaws. In particular he is a ladies man who likes a drink and has furious bouts of rage. He is also a warrior for good. He is represented in this temple as a result of the story that Pak Tai borrowed his sword and never returned it. Often, Pak Tai is depicted with the sword held tightly in his grasp, as if he were to let it go, it would return magically to its true owner. As if to recompense Leoi Dong Ban, both statues have been given swords. Moving towards the central altar, you pass Kwan Kung (關公 Guān Gōng), the god of war.

In the centre is the original image of Pak Tai. This was made for the temple and he is positioned to oversee all of his palace. The seated figure holds court here and, flanked by his soldiers, you have been granted an audience with the Emperor of the North. The black-robed and dark-faced figure exudes military power and his presence is almost overwhelming. After a few moments, you decide to excuse yourself and move to the next altar to the right. The first one contains the Three Great Emperor-Officials – Sam Gun Tai Tai (三官大帝 Sān Guān Dà Dì), sent by the Jade Emperor to govern the world. These three sovereigns are the Heavenly Official (天官 Tiān Guān), Earthly Official (地官 Dì Guān) and Waters Official (水官 Shuǐ Guān). As if to cut through the testosterone of the room and to give some compassion to the war-like deities, a statue of Kwun Yum, the goddess of mercy is in the main altar of the three on the right of the temple. The golden face shines forth motherly kindness and you feel calm and ready to continue. The last image in the altar range is Shing Wong.

Leaving the large chamber, you complete the masculine rogues gallery by entering the hall to the left of the main temple. This is the Sam Bo Din (三寶殿 Sān Bǎo Diàn) or Three Treasures Hall. The chamber houses a small museum of the temple’s artefacts, also has an altar in the far corner. The central section enshrines the Sam Ching (三清 Sān Qīng). The Three Pure Ones are the highest three gods of Taoism and are highly revered throughout all Chinese Taoist temples. On the right is a framed picture of Tai Jyut (太乙 Tàiyǐ), the Great Oneness. This is a Taoist supreme god concept that is identified as the ladle of the Plough constellation. While these deities are important, the most interesting character here is the statue on the left. Not often seen in Hong Kong, it is an image of Pang Jo (彭祖 Péng Zǔ) or The Master, a Taoist saint who lived for over 800 years and had more than 100 wives. His hundreds of children are testimony to his sexual magic of harvesting yin energy during coitus. His sexual powers came from a herbal soup he made. Seen as a father of qìgōng (氣功), practitioners come to gain his blessings for a long life.

Leaving the manly chamber and going into the annex on the right flank of the temple, you enter into a more feminine world. The small trapezoidal shrine room has one altar in it. Contained within are three mother goddesses to balance the male dominated main halls. The figure on your left Fat Mo Leung Leung (法母娘娘 Fǎ Mǔ Niáng Niang), a bodhisattva of the dead. She is possibly derived from Māyādevī, the mother of Buddha. On the right of the trio is Wah San Sing Mo (華山聖母 Huà Shān Shèng Mǔ), the mother goddess of Mount Hua in Shaanxi Province. She is often confused for Tin Hau (天后 Tiān Hòu), the most popular sea goddess in Hong Kong, but along with Fat Mo, Wah San Shing Mo is a rarity in Hong Kong. In middle is the goddess the hall is named after. Lung Mo (龍母 Lóng Mǔ), the Dragon Mother is a popular goddess in South China. She was born in Guangdong province during the Qin Dynasty (221 – 206 BCE) and raised five dragons from infancy to maturity. She and the dragons stayed together for the entirety of Lung Mo’s long life and she has become a goddess of parents and children.

After a while in the smoky chamber, joss coils smouldering in the smoke stack behind you, you go back into the main chamber and out into the front court. In the tranquil shady space, you look back into the temple. From here, it is hard to believe that such a complex group of beings is housed in the buildings. Although dominated by strong martial male gods, the temple is tempered by the female softness of mother goddesses. Both yin and yang are represented, although yang does have the edge. The temple that is laid out under the rules of fēngshuǐ seeks balance in its structure, but also in who is represented within its walls. Having had your yin and yang levelled, you leave the site and head back to the hectic action of Wan Chai’s reclaimed land.

Kinkaku-ji

Kinkaku-ji

[…] https://thetempletrail.com/pak-tai-temple-wan-chai/ (Great little blog post detailing more information about both the Hung Shing and Pak Tai Temples in Wan Chai.) […]