The pantheon of Chinese deities is bewildering and unquantifiable. The sheer number of gods and goddesses is near to impossible to categorise and account for. Thousands of local deities are worshipped alongside the more prominent figures throughout China and its diaspora. The impact of different ideologies and historical figures has been profound and what remains is a crucible filled with elements of regional and national folk-beliefs that make up the fusion religion of China. While Confucianism and Buddhism have had a heavy influence on the religious scene of China, these two systems do not emphasise supernatural deities. Instead, we must look to Shenism (Chinese folk religion) and Taoism in order to find gods. While many of them are associated with natural phenomena, a good deal are also deified historical figures. Emperors of China and their administrations never paid too much attention to the gods of the people, but they took special care to honour Heaven and the Supreme Emperor in rites advocated by Confucius. They also patronised Buddhism and Taoism as state ideologies, but the Shenism of the masses was always practiced among the rural and urban lower classes, leading various emperors to elevate popular deities by bestowing grand titles upon them. Taoism absorbed many of these gods and goddesses as it developed and the confusing amalgam that we can see today came to be.

Creation

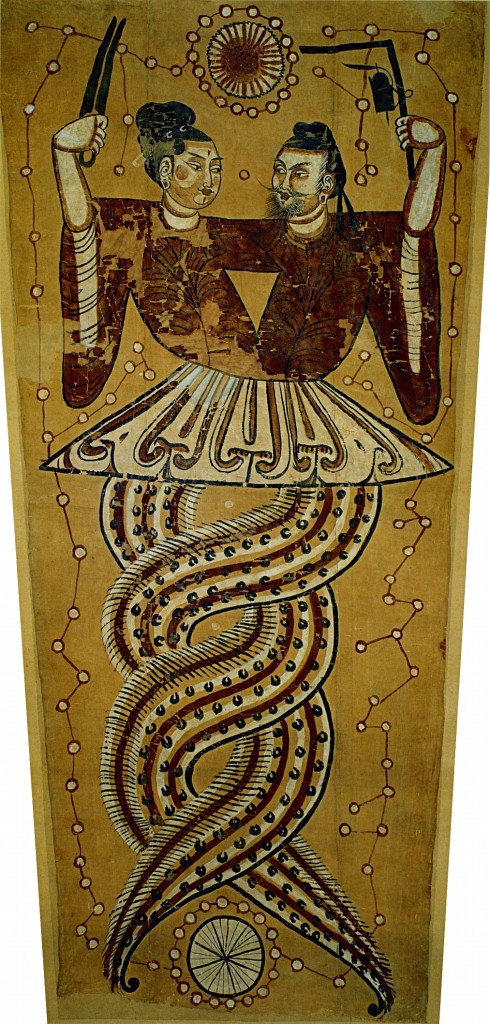

The main creation myths of China focus on the sibling pair of Fú Xī (伏羲) and Nǚwā (女媧). It is said that in the beginning, surrounded by chaos was a sleeping giant named Pángǔ (盤古). The hairy, horned giant woke up and, upon standing, split the heavens and the earth, dividing Yin and Yang. After thousands of years, he died and his body became the sun, moon, stars, mountains, rivers and forests and all else in creation. From this primordial creation, the goddess Nǚwā arrived and found that the four pillars holding heaven and earth apart were broken, so she repaired them. She then fashioned mankind from clay and, along with her brother Fú Xī, breathed life into them. Fú Xī then taught humans the arts of hunting, fishing and cooking. Based, perhaps, on an ancient tribal leader, Fú Xī is the first of the Three Sovereigns and the mythological creator of the sacred I Ching (易經 Yì Jīng) and the bāgùa (八卦) trigram arrangement. The two siblings are often portrayed with serpent’s bodies.

Tiān (Heaven)

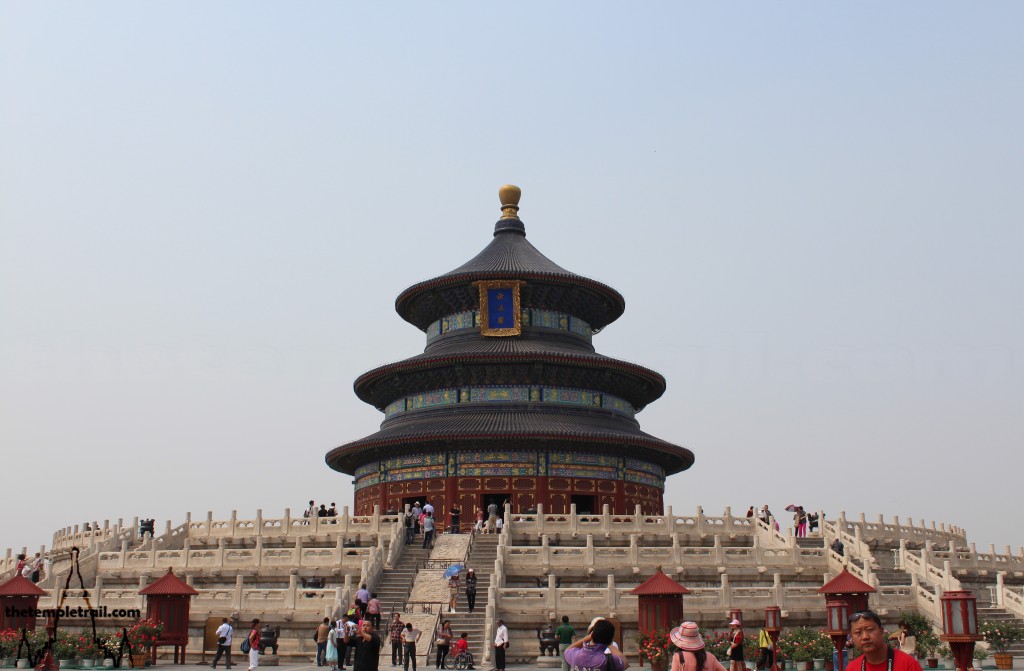

The most ancient principle in Chinese religious thinking is that of Tiān (天). Tiān means heaven or sky, but was originally depicted with a character resembling a human form. Heaven is a very important concept and, while it does not translate into a personified ‘god’ form, it is more of a cosmic force. The Confucians maintain the importance of heaven and an Emperor needed to perform elaborate rituals to ensure the continued Mandate of Heaven, so that his rule was not ended. Emperors were called the Son of Heaven. Heaven Worship continued up until the beginning of the Republic of China and the Qing emperors performed annual rites at the Temple of Heaven in Beijing.

Shàngdì (Supreme Emperor)

During the Zhou Dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE), Tiān came to be intrinsically linked to Shàngdì (上帝), previously a tribal god of the Shang and Zhou clans. Worship of the Supreme Emperor became institutionalised and the Confucians included rite for Shàngdì in the classics. The sky deity was said to act through agents, rather than personally exercising power. Over time Heaven and the Supreme Emperor became one and the same. Also known as the August Highest Emperor of Heaven (皇天上帝 Huángtiān Shàngdì), he is associated with the Jade Emperor.

Yù Huáng (Jade Emperor)

A major figure in China after the advent of Taoism, the Jade Emperor (玉皇 Yù Huáng) effectively melded with Shàngdì, as we can see by his alternative names Yù Huáng Shàngdì (玉皇上帝) and Yù Huáng Dà Dì (玉皇大帝). Some mythology has him as the creator god, but other stories have him become the Jade Emperor through Taoist attainment. As the highest of deities, he has the final say over the affairs of the universe. When mortals pray to their favourite gods, the gods then lobby the Jade Emperor on behalf of their adherents. It is a case of as below, so is above. He is the top of the Heavenly Bureaucracy.

Xī Wángmǔ (Queen Mother of the West)

Developing from a mother goddess cult from the Shang Dynasty (1600 – 1046 BCE), the Queen Mother of the West (西王母 Xī Wángmǔ) became the feminine goddess of immortality after Taoism had adopted her. Prior to that she was a wrathful plague goddess with the teeth of a tiger and tail of a leopard. The Royal Mother of the Western Paradise lives on Kunlun Mountain where she is responsible for the heavenly peach garden. The peaches, which are served every 6000 years give immortality to those who eat them.

Yán Wáng (King of Hell)

The god of death can trace his roots back to the Indian god Yama. Also known as Yán Luó Wáng (閻羅王), he presides over hell (地獄 dìyù). This is not the hell in the Judeo-Christian sense, but rather the place where all souls go for judgement. Yán Wáng (閻王) is the judge and he has a book containing all the deeds of all souls. Those who are meritorious will obtain good future lives, whereas the wicked will be punished and tortured. People in China pray to Yán Wáng on behalf of their deceased loved ones, in the hope that they have a good afterlife.

Guānyīn (Goddess of Mercy)

Originally a male bodhisattva from the Mahāyāna Buddhist tradition, Guānyīn (觀音) emerged as a Chinese female saint. As her popularity increased, she was absorbed by Taoism and folk religion as the Goddess of Mercy. Guānyīn is easily the most recognisable goddess in the Chinese pantheon and is revered by almost all Chinese people regardless of their religion. The goddess version of Guānyīn, as opposed to the Buddhist one, is identifiable by the presence of Jade Girl (玉女 Yùnǚ) and Golden Boy (金童 Jīntóng), her child attendants. Her crown also does not have the image of the Buddha Amitabha in it.

Māzǔ (Grandmother Ancestor)

Possibly the most worshipped goddess in the world, Māzǔ (媽祖) is the most popular goddess in the Chinese diaspora. Known more often as Empress of Heaven (天后 Tiān Hòu), her meteoric rise to the highest position in heaven is incredible. She was born as a mortal called Lín Mòniáng (林默孃) in Fujian Province in 960 CE. She learned the Taoist arts and used her powers to save her brother and father during a typhoon. After she died aged 27, she became a patron saint of fishermen on her home island of Meizhou. As her popularity increased, her fame spread throughout the sea reliant southern Chinese people. Emperors bestowed titles on her and within a few hundred years, she became the Empress of Heaven. Nowhere is her influence more apparent than on Hong Kong, where no less than 80 temples are dedicated to Tin Hau.

Běidì (The Northern Emperor)

The Barefoot Northern Emperor is a very important god in Chinese tradition. He has a number of names aside from Northern Emperor (北帝 Běidì), he is called the Black Emperor (黑帝 Hēidì) and the Great Emperor of the Northern Peak (北岳大帝 Běiyuèdàdì). Originating in the Shang dynasty collapse in 1046 BCE, he has been worshipped for thousands of years. He gained particular support from Emperor Huizong of Song (宋徽宗 Sòng Huīzōng) in 1118 when the god appeared to him after a shamanic ritual. The martial god rules over the dark heaven, or jade void. He is a winter deity and is seen as a powerful exorcist. He is always depicted without shoes alongside a snake and turtle, making him one of the more easily identifiable of the gods. He is hugely popular in Hong Kong, where he is known as Pak Tai. Taoists also refer to him as Xuán Wǔ (玄武), the Mysterious Warrior.

Wénchāng Wáng (God of Culture and Literature)

Also known as Wénchāng Dìjūn (文昌帝君), Wénchāng Wáng (文昌王) was likely a mortal who fought in a rebellion in Sichuan in the 4th century CE. The god was officially deified during the Yuan Dynasty (1271 – 1368), but how he came to be associated with literature is unclear. He is represented in the heavens by a constellation that almost fits into what Western astronomers call the Big Dipper. He is worshipped primarily by students and their parents in the hopes that they are successful in their studies.

Kuí Xīng (Chief Star)

Kuí Xīng (魁星), known also as “Great Kui the Star Prince” (大魁星君 Dà Kuí Xīng Jūn), the impish looking god is worshipped for success in examinations. Originally presiding over the Imperial Examinations (科舉 Kējǔ), the god is much older than Wénchāng Wáng, who somehow usurped Kuí Xīng’s role. For this reason, Kuí Xīng always sits on a separate altar from the other god. He is depicted standing one-footed on the back of a turtle to represent coming first in the Kējǔ and holding a calligraphy brush in his hand. He is associated with the four stars that make up the spoon of the Big Dipper constellation.

Léi Gōng (Lord of Thunder)

Transformed from being a mortal to a god by eating a peach from a magical tree, the thunder god is an unusual looking figure. Appearing very much like the Indian Garuda, Lord of Thunder (雷公 Léi Gōng) is a bird man who causes the thunder to sound. He carries a mallet to make the thunder and a chisel in order to punish the wicked. He is married to Lightning Mother (電母 Diàn Mǔ) and is associated with other elemental spirits; Master of Rain (雨師 Yǔ Shī), Earl of Wind (風伯 Fēng Bó) and Cloud Boy (雲童 Yún Tóng).

Guān Dì (Emperor Guan)

In life, Emperor Guan (關帝 Guān Dì) was a legendary general of the Three Kingdoms period (220 – 280 CE) named Guān Yǔ (關羽), who was loyal to the State of Shu. The warrior made a blood oath to serve with his sworn brothers Zhāng Fēi (張飛) and Liú Bèi (劉備). When Liú Bèi founded the State of Shu, Guān Yǔ followed him. Eventually, the famed soldier was captured and executed by Sūn Quán (孫權), the Emperor of Wu. Also known as Lord Guan (關公 Guān Gōng), the bearded, red-faced warrior came to be revered almost universally throughout China as a protector of people, businesses and homes. As the patron of fraternities, he is the god of both the police and the triads. In Hong Kong, he is the god of war and is referred to as Mo Tai (武帝).

Cái Shén (God of Wealth)

One of the most important deities in Chinese culture is the God of Wealth (財神 Cái Shén). He has many incarnations and aspects that are sometimes represented individually in their own statues. The most common is the basic image of a seated man holding gold bars. This god is the Wealth Star Lord (財帛星君 Cái Bó Xīng Jūn), originally a county magistrate of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386 – 535 CE) called Lǐ Guǐzǔ (李詭祖). Another popular god of wealth is Bǐ Gān (比干), uncle of the evil King Zhou of Shang (商紂王 Shāng Zhòu Wáng), who met with a gristly end and was deified after the Zhou Dynasty came to power on the fall of Shang in 1046 BCE. Another popular god of wealth is Zhào Gōngmíng (赵公明), the Martial God of Wealth. Also deified after the Shang collapse, the black skinned and bearded figure is depicted in a fearsome manner riding a tiger and holding an iron cudgel. People pray to these gods for money and financial success.

Nézhā

Nézhā (哪吒), the boy god of war is an interesting character who can possibly trace his origins to the Indian deity Balakrishna. Created after the fall of the Shang dynasty in 1046 BCE, the god is also known as the Third Lotus Prince (蓮花三太子 Liánhuā Sān Tàizǐ), or the Marshal of the Central Altar (中壇元帥 Zhōng Tán Yuán Shuài) to the Taoists. Having defeated dragons, he is a powerful protective deity who wields the divine weapons; the Fire-tipped Spear and Universe Ring. He flies through the skies on his Wind Fire Wheels. The youthful god has a small, but prominent temple in the centre of historic Macau, where he is called Na Tcha.

Bǎoshēng Dàdì (Life Protection Emperor)

Particularly popular in Taiwan, Bǎoshēng Dàdì (保生大帝) is a god of medicine. While many lower ranked gods perform this function, the Life Protection Emperor is the highest of them all. Originally a doctor called Wú Běn (吳本) who practiced during the Song Dynasty, he was deified upon his death in 1036 CE. As a doctor, he was famed for his medical prowess and as a Taoist practitioner, he performed miracles. He is said to have been taught exorcism by the Queen Mother of the West. The Baoan Temple in Taipei is dedicated to the god and is always bustling with worshippers.

Cháng’é (Goddess of the Moon)

The consumption of moon cakes during the Mid-Autumn Festival in China is a homage to Cháng’é (嫦娥), the Moon Goddess. Her story starts with her husband, Hòu Yì (后羿), the divine archer. The world was plagued by ten suns that caused the crops to fail. Hòu Yì shot down nine of the suns, personified as three-legged crows, and was given the elixir of immortality as a reward. He did not want to consume it and leave his wife Cháng’é as a mortal. One day, when Hòu Yì was out, his jealous apprentice Féng Méng (逢蒙) came to steal the elixir. Realising that he would overpower her, Cháng’é drank the potion and ascended to the moon as a goddess, wishing to stay as near to her husband as possible.

Lóng Wáng (Dragon King)

The Dragon King (龍王 Lóng Wáng), sometimes known as the Dragon God (龍神 Lóng Shén), is the personification of all dragons (龍 lóng). Dragons are water deities and are thought to bring flooding and drought through their control over the rains. In ancient times, complex rituals were performed to appease them. The most important of the dragon deities are the Dragon Kings of the Four Seas (四海龍王 Sìhǎi Lóng Wáng), who are often found in temples of other sea deities, they usually are shown with dragon heads and human bodies. Worship of the Dragon King is not as prevalent today as it was when more of China was water dependant and fishing was a key trade for most coastal dwelling Chinese.

Èr Láng Shén (Second Son God)

Also known as Great Emperor of Flowering Brightness (花光大帝 Huá Guāng Dà Dì), the Second Son God (二郎神 Èr Láng Shén) is said to be the child of the Jade Emperor’s sister and the greatest warrior god of heaven. He has a truth seeing third eye in the centre of his forehead. Historically, he may have been the son of a governor of Sichuan during the Qin Dynasty (221 – 206 BCE) who helped to build advanced irrigation systems. The historical persona has been superseded by the deified one and his cult was absorbed into Taoism, spreading his fame throughout China.

Bāo Gōng (Justice Bao)

Justice Bao (包公 Bāo Gōng) was a magistrate of the Northern Song Dynasty (960 – 1127 CE) in Kaifeng, China. Born to a middle class family, Bāo Zhěng (包拯) worked hard to become educated. Upon passing the Imperial Examination, he became a magistrate, a role that was normally performed by corrupt men looking to fill their pockets. He was fair and honest and stood up for the poor. He had no qualms about bringing the ruling classes to justice and even executed a member of the imperial household for his crimes. After his death, he became a black-faced deity who can help bring solutions to legal problems and justice for those in dispute.

Sān Xīng (Three Stars)

Better known as Fú Lù Shòu (福祿壽), these three folk figures are personifications prosperity, status and longevity. Each is a star in the skies and they came to particular prominence during the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644 CE). The Three Stars (三星 Sān Xīng) are some of the most recognisable figures of the Chinese pantheon and are found in most homes in some form or another. They represent the core values of the Chinese people and are much loved by the population as a whole, including the more secular.

Tài Suì

The sixty generals (太歲 Tài Suì) take it in turns to look after the world for one year. These gods rotate the power of dominion of human fate in sixty year cycles. They are not seen as benevolent and need to be appeased so that they do not bring misfortune. Depending on your birth year, when certain Tài Suì when in command can bring great trouble your way. In temples, an array of all sixty statues can be found and a sign is put in front of the governing god. These gods are often accompanied by Dǒu Mǔ (斗母), the Goddess of Measure and personification of the Pole Star. She is responsible for the measurement of time and is sometimes depicted with the Twenty-eight Mansions (二十八宿 Èr Shí Bā Xiù), which are constellations in the Chinese system. These stellar gods are very important to the Chinese, as they believe that the impact their daily lives.

Chénghuáng (City God)

The City God (城隍 Chénghuáng) was originally the god of the moat and walls of a city. He eventually came to be responsible for the people of the city and particularly of the dead. At Chénghuáng temples, people pray for a good afterlife for their ancestors and burn joss items, such as paper money and other paper versions of worldly goods for their deceased relatives to receive. The Chinese have many beliefs concerning what happens once we die, but a prevalent one is that they need their living descendants to make offerings for them to use in the next life so that they do not become hungry ghosts (餓鬼 èguǐ). The City God seems to have absorbed some of the responsibility for presiding over this from the King of Hell.

Tǔ Dì Gōng (Earth God)

The jolly looking figure of the Earth God is found all over China and he is one of the most ancient, widespread and popular gods among the everyday people. The Lord of the Soil and the Ground (土地公 Tǔ Dì Gōng) is responsible for local areas and villages. He is somewhat akin to a local level administrator in the Heavenly Bureaucracy. In charge of protecting the people of the district, he is often confused with another tutelary deity called the Righteous God of Virtue and Blessing (福德正神 Fúdé Zhèngshén). The wealth factor is very prominent and he is depicted as a bearded old man holding a gold tael. Villagers pray to him for the wealth of the land and agricultural success. His shrines are found in every village and district in traditional Chinese areas. He is sometimes depicted with his wife Grandmother of the Soil and the Ground (土地婆 Tǔ Dì Pó), but has an alternate consort, the Queen of the Earth (后土 Hòutǔ).

Zào Jūn (Stove Master)

The most well-known household deity is the Kitchen God. Dwelling in every kitchen in each Chinese home, the Stove Master (灶君 Zào Jūn) protects the hearth and family, but also reports on their comings and goings to the Jade Emperor. Just before the Lunar New Year, he must return to Heaven and give his report. People will often smear his effigy’s lips with honey to sweeten his words. The activities of the household around this time a blur of cleaning and diligently getting the home ready for the report of the god and the coming New Year.

Zhōng Kuí (The Demon Queller)

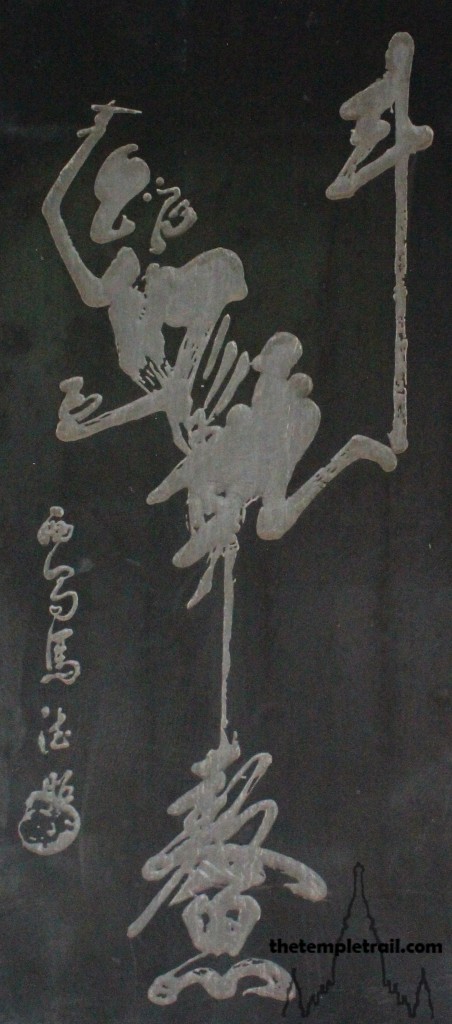

Zhōng Kuí (鍾馗), the ghost controlling god, is often found on doors and in people’s houses to protect the living from the dead and demonic forces. He was originally a scholar who passed the Imperial Examination, but was stripped of his title due to his ugly appearance. The dark, gristly figure then killed himself in protest by smashing his head against the imperial palace doors. In hell, Yán Wáng saw potential in Zhōng Kuí and made him the King of Ghosts. Much later, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (唐玄宗 Táng Xuánzōng), was being severely ill. One night, he had a dream that he was being troubled by a small ghost. Zhōng Kuí appeared and captured the ghost and introduced himself to the Emperor. When he awoke, he was well again and he commissioned a painting of Zhōng Kuí, thereby making him a popular deity.

Mén Shén (Door Gods)

Apart from Zhōng Kuí, another set of gods can be found on the doors of Chinese buildings. While there are many various kinds, the most common Door Gods (門神 Mén Shén) are the military pair called Qín Shūbǎo (秦叔寶) and Yùchí Jìngdé (尉遲敬德). Emperor Taizong of Tang (唐太宗 Táng Tàizōng) was being plagued at night by the ghost of a Dragon King he had executed. Eventually, he had his two generals Qín Shūbǎo and Yùchí Jìngdé posted outside his bedroom doors and slept soundly from that point on. Images of the two guardians began to be put on doors throughout China and they became the most popular door gods.

Hóng Shèng (Hung the Saint)

Known as Hung Shing in Cantonese, but often called Tai Wong (大王 Dà Wáng), meaning “Great King”, Hung the Saint (洪聖 Hóng Shèng) was an official of the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE) serving in Guangdong. His good service and scientific approach to weather prediction earned him deification after his early death. Now a sea god responsible for the Southern Sea, many temples to Hung Shing can be found by the shore in Guangdong and Hong Kong.

Lóng Mǔ (Mother of Dragons)

The Dragon Mother (龍母 Lóng Mǔ) was born in Guangxi in 290 BCE. She found an egg in the river and took it home. The egg hatched and out came five serpents that she cared for like a mother. The snakes became dragons and Lóng Mǔ, through the power of her dragon children gained control over the rains. When the first emperor of China, Qín Shǐhuáng (秦始皇), heard of her powers, he summoned her to court, but her dragons did not allow the boat to leave Guangxi and she remained there until her death. Being a Southern goddess, she is particularly worshipped in the South of China. In Hong Kong, there is a temple dedicated especially to Lung Mo, as she is called in Cantonese, on the island of Peng Chau.

Huáng Dàxian (Great Immortal Huang)

Although he originally came from near Hangzhou in Zhejiang Province, this Taoist immortal, came to be worshipped as a god in Guangzhou and Hong Kong, where he has the better known name Wong Tai Sin (黃大仙 Huáng Dàxian). Born to a poor family, Wong Tai Sin was a shepherd who learned Taoism from an immortal and after years of practice in solitude on Red Pine Mountain, was able to perform miraculous feats. His immense popularity in Hong Kong is due to an image brought by a traditional medicine practitioner from Guangzhou in the early 20th century. People visiting his shop started praying to the icon and over time, the huge temple Sik Sik Yuen Wong Tai Sin was built to accommodate the faithful.

Chē Gōng (Lord Che)

Known as Che Kung (車公 Chē Gōng) in Guangdong and Hong Kong, the Great Warrior was a general of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127 – 1279 CE). He is said to have helped the last two child emperors of the dynasty escape the Mongol invasion. He is particularly important in the South of China and is especially revered during Chinese New Year. He is said to have the power to avert plagues and people pray to him for health and fortune. He is associated with metal pinwheels and his followers spin them after praying.

Tam Kung (Lord Tam)

Tam Kung (譚公 Tán Gōng), the boy god, may be historically grounded in the last child emperor of the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 CE), who escaped to the South of China following the Mongol invasion. Popular folk belief in Hong Kong and Macau, where his cult is most evident says that he was an immortal from Huizhou in Guangdong who could cure the sick as a child. He is said to have become an immortal as a young man, but that he appears as a child to fishermen in order to cure their ills and predict the weather. The sea deity is usually depicted as a child holding a bell.

Wat Lok Molee

Wat Lok Molee

I would love to see Tǔ Dì Gōng catch on with conjure workers in the U.S.

Great piece of work. Has helped me gaining more thorough insight to practices of the Chinese people. Please, if u can, continue working on this and to continue publishing. I am excited to read and learn more from you.

Thank you very much for your nice comments!

Tom

You have a great piece of art that should continue more until there no more XD….

Fascinating essay. I like the combination of picture and text, and your comments on and descriptions the gods are very well done. They give insight into the culture — each craft has a god, the forces of nature and aspects of life (like wealth and luck) are personified by a god, ancestor worship is given a god or two, important military and governmental leaders are deified. I will return to this blog post and think about it some more.

Recently, through a memory of having seen a few of the Terracotta Warriors, I began learning about Chinese history and culture. https://irissansfrontieres.wordpress.com/2016/10/18/art-from-greece-through-persia-to-china-before-the-silk-road/

Thank you for your nice comments Iris. I am please you enjoyed my piece about Chinese gods. I am very much an amateur Sinologist, but try my best. Tom

Love Chinese tradition and China. It is too great.

I am interested in this religion .Why as I was told; old wooden Gods are taken to the temple to be burnt?

Hi Alex

That is not strictly true. Most people in China do not have wooden idols of gods. They are more often than not made of ceramic. When a statue of a god is broken, it is seen as being inauspicious or unlucky. The gods are taken to the temple so that they are no longer in the house, but not “thrown away”, as that would be terribly bad luck. The Taoist priest at the temple will know how best to deal with the unwanted statue. There are sometimes shrines by the roadside that are full of broken statues – sort of “gods’ graveyards”.

In Japanese tradition, there are wish dolls made of papier mache called “daruma dolls”. The idol is bought, a wish is made and one of its eyes painted in. When the wish comes true, the second eye is painted in. After a year, the dolls are taken to the temple to be burnt, as they are no longer needed.

I hope that answers your question!

Tom