The old streets of the Insa-dong neighbourhood of Seoul have presented you with labyrinthine choices. Each street seems to lead to an even smaller twistier one. After a lunch of the spicy local nakji deopbap (spicy octopus rice), you feel full of energy and ready to negotiate the streets once more. Bursting out into the larger main street, you head through Tapgol Park, stopping briefly to look at the beautiful glass encased Wongaksa Pagoda. The twelve meter tall spire of solid marble dates from 1467 and is a beautiful work of art. Built by Sejo, the seventh king of the Joseon Dynasty, it is a standout pagoda in Korea. The Joseon Dynasty are the main interest of your final destination and after a few minutes, you head on to the shrine that honours the former ruling family of Korea. After walking through another small park and a section of ancient wall, you find yourself at the gates of Jongmyo, the shrine that houses the memorial tablets of the kings and queens of the Joseon Dynasty.

The Joseon Kingdom lasted for 500 years in Korea from 1392 until 1897, when the kingdom was declared as the Korean Empire. In 1910, the Japanese Empire took full control of Korea, thereby ending the half millennial rule of the Yi family. Yi Seong-gye founded the Joseon Dynasty in 1392 in the messy end of the previous Kingdom of Goryeo. The ruling Wang family had been in power for the best part of 500 years and after eventually freeing itself from the Mongol influence of the Yuan Dynasty in China, found itself on the brink of collapse. When the Ming Dynasty of China came to demand some territory in 1388, the Yuan supporting Korean General Choe Yeong sent the General Yi Seong-gye to invade the Liaoning Peninsula. This political move was made by Choe, as Yi was in charge of the opposing faction in the Goryeo royal court and supported the Ming. The move backfired on Choe and at Wihwa Island, Yi turned his army back, knowing he had the support of the Korean nobles, the people and the Ming of China. He staged a coup d’état, first deposing King U and installing his 7 year old son Chang as king. Within a year, both father and son were put to death under orders of Yi, who continued building his powerbase in court. Yi then installed another puppet King Gongyang. After the assassination of Jeong Mong-ju, the last of the supporters of the Goryeo Dynasty, Yi Seong-gye had Gongyang and his family put to death and ascended to the throne himself in 1392.

The Oedaemun gate stands before you and passing under its simple, but elegant structure, you enter into the large grounds of the shrine. In 1394, two years after seizing control of Korea, Taejo of Joseon, as he was now called, moved the capital from Gaegyeong (Kaesong) to Hanseong (Seoul). The following year, 1395, work was started on the supreme state shrine of Jongmyo. The position of the shrine in location to the royal Gyeongbokgung Palace adheres strictly with Confucian rules about placement of ritual buildings. The shrine for the spirits of kings and queens is to the east and to the west of the palace is the Sajikdan (Altar of Soil and Grain). The shrine was expanded on a number of occasions in order to house more family member’s memorial tablets. Following the path from the gate a short way, you see that the centre of the flagstone path is reserved for the spirits of the dead. This central section is known as the Sillo. When a king had his tablet installed in the shrine, the officiants carrying it walked on the Sillo. The path on the right, the Eoro, was for the King and the Sejaro on the left for the crown prince. Heeding the signs, you do not tread on the centre stones.

You pass a pond on your left and come to an identical one to the right of the path. The square pools, known as jidang, each have a circular island in their centre. In East Asian cosmology, earth is represented as a square and heaven as a circle. In Beijing, the Altar of the Earth (Dìtán) is square, while the Altar of Heaven (Tiāntán) is round. Here, the two shapes together represent the connection of earthly matters with those of heaven. The symbolic union of the two shows how the past kings and queens are still influential on the earthly plain, despite having passed into the heavenly realm. On the second island that lies before you now, you see an old and gnarled juniper tree. The juniper has a special significance to the dead in Korean culture, and is commonly found in charnel grounds around the country. The presence of the tree is apt, as this is a palace of the dead. In the nearby palaces built for the living kings, pines can be found instead, representing longevity in the hope the reigning family members had a long life.

Passing the pond, you come to a set of buildings with more practical purposes. The first of the cluster is the Mangmyoru. Although you cannot enter the chamber, it served as a library and meditation pavilion. Kings were meant to use the space to consider what previous rulers had done during their reigns and think about what they can do in their own. The building rests next to two walled compounds. To the left is the larger one that contains the Hyangdaecheong. This building, also out of bounds, was the preparation space for rituals. It was where offerings and incense were kept and where officials waited for their presence to be needed in rites.

Behind the Mangmyoru is the smaller walled area, which contains one small hall. It is called the Gongminwang Sindang and is a shrine dedicated to Gongmin of Goryeo, the predecessor to King U, who was deposed by Taejo. The shrine has a portrait of the king bride from the previous dynasty and his Mongolian; its presence here is somewhat baffling. Gongmin’s 23 year reign was plagued with problems from foreign invaders, to internal strife caused by the king’s mismanagement of the country. He was eventually assassinated in his sleep by a member of the Choe family. His successor, King U came to the throne at 11 years old under the power of Yi In-Im, an official who was eventually removed by General Choe and General Yi Seong-gye (Taejo). While some believe that the shrine was meant to legitimize the Joseon Dynasty by tying it with a Goryeo ruler, this seems like an unlikely situation. Gongmin was not recognised as a king after his death, as he had declared himself to be king and was unpopular. There is a story that the portrait blew into the grounds of Jongmyo as it was being constructed and that it was taken to be an omen. The decision was made to enshrine the portrait, so as to prevent the malignant spirit of the past king from creating problems. You feel as this is a more tangible explanation, especially as you see that the location of the shine is anything but auspicious.

Walking on to the next group of buildings, you come to a walled enclosure containing three chambers. Climbing a flight of stairs at the southern entrance, you note that the Eoro and Sejaro pathways split in the courtyard within. The halls here, that progressively shifted further eastward as the main hall of Jongmyo was extended over the years, are collectively called the Jaegung. Standing in the courtyard, you are surrounded by three buildings. The area was for the purification of the king and prince before the sacrificial ancestral rites at the main shrine. Ahead of you, now used as a display room, is the Eojaesil on its raised platform. This room was the king’s quarters, while the less elaborate hall on the right, the Sejajaesil, was the prince’s quarters. The building on the left is the Eomokyokcheong, the bath house. A large bowl on the corner of the Eojaesil’s platform catches your attention. The deumeu (big bucket) had a practical and magical purpose. It is an early fire hydrant, that contained water to put out fires, but on the preventative side, it is said that the evil fire spirit is so repulsed by his own reflection on the surface of the water, that he runs away upon seeing it.

From the western gate of the Jaegung, you continue on to the eastern gate of the Jeongjeon. Before entering the main hall of the complex, you inspect the elements around you. Prior to reaching the corner of the walled enclosure you see that the Eoro and Sejaro paths have separated away from the Sillo. The latter, reserved for the spirits connects directly to the grand southern entrance of the Jeongjeon, whereas the other two paths enter at the eastern gate. Before you follow the king and prince into the shrine, you take stock of the buildings to the right of the enclosure. Behind two stone platforms are a small collection of structures with a practical ritual use. On the far right of the group is a small enclosure that contains the Jejeong (ritual well). Water from this well was used in the Jaegung for ritual cleansing, but also in the buildings to the left of it. The rooms centre around the Jeonsacheong. Rebuilt in 1608 after the Japanese destroyed it in 1592, the Jeonsacheong is the ritual kitchen. Used for preparing food for offering, the small complex is now shut to the public, but looking through the gates, you see mortars on the ground, still good enough to be used. In front of the kitchen are two stone platforms. The smaller one is the Seongsaegwi and was used for inspecting animals slated for sacrifice. If the animal was deemed worthy, it would be sacrificed in the rituals. The larger platform is called the Chanmakdan and was employed as an inspection table for the prepared food, to see if it was fit for use on the altars in the shrine.

You look at the functional looking building to the right of the eastern gate. This is the Subokbang, where the shrine guards were quartered. Stepping past the guardhouse, you get back on the walkway before the gate. A platform lies in the middle of the path and another to its right. These are Panwi and were where the king and crown prince paused in their procession to pray and pay respects before proceeding through the gate. You emulate the men of the past and walk through into the most glorious and expansive part of Jongmyo. Trying to take in the whole area, you are finally inside the Jeongjeon compound.

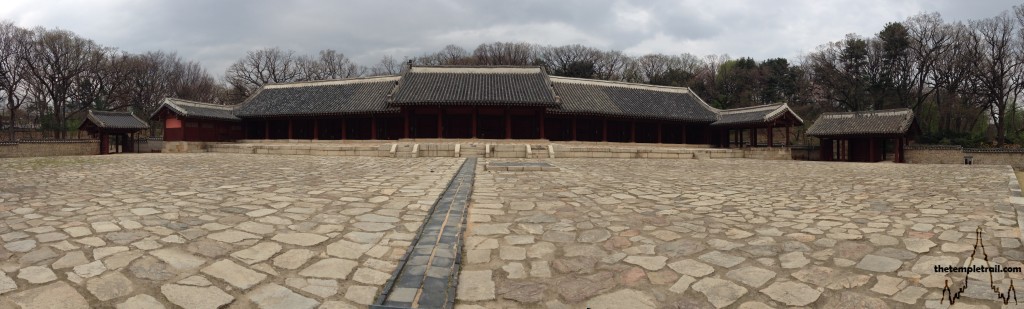

Since its initial construction in 1395, the Jeongjeon has been expanded on several occasions. Starting with seven spirit chambers, it was expanded to eleven in 1546. The Japanese burned the hall to the ground when they invaded in 1592, but sixteen years later in 1608, it was rebuilt. Four more chambers were added in 1726 and by 1836, the count stood at its present 19 chambers. Standing at the short edge of the hall, it seems to stretch on impossibly far. In front of the hall is a vast stone terrace called a woldae that sits on the sacred myojeong ground. The woldae, or moonlight plain, is made up of two sections, the larger, Ha-woldae (lower platform) is split down the middle by the dark stone Sillo that crosses it from the southern gate to the central staircase of the Sang-woldae (upper platform). This route is for the spirits and officials who carry the tablets. Next to the path on the Ha-woldae is the Bualpanwi stone platform. This platform was the parking space for the carriage that carried the tablets to the shrine. All of the stones on the woldae, like those of the Sillo are rough and uneven. This was purposefully done in order to force the living to walk slowly and solemnly. Climbing up onto the lower woldae, you move slowly in for a closer look at the sealed main hall.

The purpose of the Jeongjeon is to house the Sinju (spirit tablets) of kings and queens of the Joseon Dynasty. When they died, it was believed that the spirit left their body. This is a belief that can be found in Chinese culture as well. Sinju are made out of chestnut wood and are the repository for the souls of the deceased. Korean tablets are similar in many ways to those found in neighbouring countries, with one significant exception. They have a small hole in their centre through which the spirit contained within can enter and leave the Sinju. This is a fundamental difference in practice and belief from other countries. The rules of dealing with the tablet and memorial rituals are all Confucian and are in accordance with the ethic of filial piety. After a king died, their Sinju would remain in the palace for the traditional mourning period of three years. After that time, the tablet would be ceremonially taken to Jongmo to be enshrined in a ceremonial manner called Bumyo. Arriving at the southern gate of Jeongjeon and coming to the Bualpanwi on the woldae, the tablet would be accompanied by musicians and dancers from the west gate and the current king and prince from the east gate. The enshrining ceremony was a colourful event that conformed to strict Confucian codes of ritual.

Standing on the woldae you picture the scene in your head. The far western spirit chamber is the most important and therefore holds the tablet of Taejo. West is the most prestigious position for the dead, as opposed to east for the living, copying the rising and setting of the sun. The altars in the halls reflect this too and the king is on the western side, with his queen or queens in centre and east. Before the Japanese burned the shrine down in the late 16th century, the tablets were hidden in the home of a commoner for safe-keeping. These were restored after the reconstruction. Looking at the incredible wooden structure, you are awed by the size of it, but also by the 49 Sinju that lie within. Also incredible is the lesson in Confucian hierarchy and order. The shrine halls have higher walls than the side rooms, which in turn are higher than those of the roofed corridors.

Backing away from the powerful structure, you step off the woldae and check out the two smaller shrines on the southern edge of the enclosure. The long Gongsindang enshrines the tablets of subjects who served the kings well and are therefore kept close to them in order to serve them further in the afterlife. The Chilsadang is a shrine to the seven gods of heaven. Prayers were made at the shrine, once more with Confucian rituals, to make sure that royal and state affairs went without any hitches. After looking back at the incredible Jeongjeon one last time, you pass through the western gate and take the path to the final compound of the complex.

The decision was made in 1421 to build a secondary shrine for kings who had not achieved as much as the great ones. Rather than keep all of the ancestor tablets in the Jeongjeon, some were moved to the newly constructed Yeongnyeongjeon. The rearrangement of kings and queens based on their merits was a fluid process and one could be kept in the main hall until someone superseded their achievements. This meritocratic system reflects the Confucian ethics that were followed by the state. One of the central tenets of Confucianism is that the ruling class should lead by example and that their merits are what lead them to positions of power. To rank past kings by merit fits the system perfectly. This hierarchy is reflected in the size of the hall compared with the Jeongjeon. The reason that the Jeongjeon was simply not expanded at that time, was so as not to upset the Chinese Ming Dynasty. The Ming ancestral shrine could not be surpassed without causing trouble, so rather than making more spirit chambers, they opted to build the Yeongnyeongjeon.

Sinsil (spirit chambers) are very formally attired inside. Yellow curtains are used to cover the ceiling and walls and another is on the inside of the entrance. The chamber is meant to be like the royal bedroom used by the monarchy in their lifetime. The ceiling is decorated to look like heaven and the Sinju tablets are kept in chests at the back of the Sinsil. Yeongnyeongjeon has 16 chambers and as you look at it from its woldae, you note that the centre of the structure is taller than the two sides. The four chambers in the raised section contain the spirit tablets of Taejo’s ancestors, who were not royalty. They are enshrined as an act of filial piety and in recognition of the fact that without them, the Joseon Dynasty would not have been. The six chambers on either side contain relocated kings and queens that once were kept in the Jeongjeon.

The woldae and that of the larger shrine are incredible platforms. Standing on this one, you can imagine the scene during the annual Jongmyo Jerye. The Confucian ritual is still performed each year on the first Sunday of May. Originally, it happened five times a year at Jeongjeon and twice at Yeongnyeongjeon, but these days, it is observed only once for both. The ceremony incorporates music, dance and sacrifice. After assuming their positions on the courtyard, the participants begin the tripartite ritual. The three sections are welcoming the spirits, entertaining the spirits and sending the spirits to heaven. Offerings of fur, blood and entrails are made and greased liver, mugmort and millet burned in a brazier. Food and wine are offered to the spirits and then consumed by the officiants. The most well-known part of the ritual as the music, known as the Jongmyo Jeryeak. The songs of praise were composed by the Renaissance man King Sejong in 1447. The polymath king, who is also known for creating the Korean writing system, is enshrined in the Jeongjeon. The music that is played on traditional Confucian instruments such as the pyeongjong (set of bronze bells) and the pyeongyeong (set of stone chimes) is accompanied by ritual dance. The Ilmu is divided into two sections, munmu (civil dance) and mumu (military dance).

Today the shrine has a ghostly quiet about it. Paying your respects to the spirits, you take your leave from the shrine and follow the path back to the front entrance. Jongmyo is a place of the dead. Even during the Japanese occupation in the 20th century, stories of occupying soldiers dying while staying at the shrine abounded, resulting in the Japanese forces steering clear of the place. For you, it has been a peaceful, rather than a frightening experience. The spirits of the dead kings and queens are at peace. They seem to be content with their yearly tribute and have not meddled too much in the affairs of the living. Stepping out of the compound, you walk down the quiet street that runs along the wall of Jongmyo and end up on a busy major road of the Korean capital. Jongmyo may be the place of the dead, but outside of its protective bubble, Seoul is very much alive.

Khalsa Diwan

Khalsa Diwan