The ferry from Lantau Island brought you to the New Territories shore at the once sleepy Tuen Mun. Jumping on board the light rail train that takes you through the growing commuter area, you pass Castle Peak home to the oldest Buddhist temple in Hong Kong, Tsing Shan Monastery. Staying on the train past the stop for the monastery known for being the location for scenes in the Bruce Lee movie, Enter the Dragon, you have another destination in mind. As the train gets to a nondescript residential stop, you get off and walk towards a chain link fence that protects hundreds of bonsai trees. A gate leads to a path that takes you through to the side entrance of a temple known for the diminutive trees you saw in the bonsai nursery. You are entering the mysterious Taoist temple of Ching Chung Koon.

Ching Chung Koon (青松觀 Qīng Sōng Guàn) or Green Pine Monastery is a large Taoist temple founded in Kowloon in 1949 by theDragon Gate Sect (龍門派 Lóng Mén Pài) of the Complete Reality School (全真派 Quán Zhēn Pài) of Taoism. Originally a rural retreat, it moved and grew over the years until it became the busy temple complex that exists here today. Dedicated to the immortal Leoi Dung Ban (呂洞賓 Lǚ Dòngbīn), the name Ching Chung is a reference to the green pine tree that is associated with the immortals of Taoism. The evergreen tree is symbolic of immortality and longevity, as it remains green throughout the seasons. It is said that Lǚ Dòngbīn likened a righteous man to the ching chung pine tree. The temple flourished in its early years due to an influx of refugees from China and it sought to provide for the needs of these people. The temple provided an affordable traditional medical clinic and vegetarian food, a service that continues to this day. As the temple needed to grow, land in Tuen Mun was acquired and larger structures were constructed in the 1960s and 70s. The temple is also very popular as a final resting place for the cremated remains of local people, so it has expanded constantly in order to provide halls that can fit in all of ashes.

Walking along the side path into the temple complex, you pass a row of gnarled bonsai trees. Some have ceramic figurines in their pots to create the illusion of a miniature scene. The diminutive size of the trees gives nothing away of their age, but some of them are hundreds of years old. These bonsai take centre stage in the temple’s annual bonsai show, held between March and May each year. Passing large administrative buildings on your left, you note that they contain medical facilities and other community support projects. Ching Chung Koon’s organization has done incredible charity work and has established eight free schools, care for the elderly in the form of relief supplies and nursing homes and two traditional medicine clinics. While the buildings are testimony to the good work done by the temple, they are of little interest architecturally, so you descend a large set of steps to the right and make your way towards the rock garden.

The rock garden is a tranquil spot that is used for meditation and reflection. As you enter into the small, but ornate space, a sense of calm descends upon you. Rocks, trees, flowers, ponds, a pavilion and a waterfall all meld together into a harmonious environment that settles your mind and gives you space for clarity. Climbing the rock path to the top of the waterfall, you see how the Taoist tradition of balancing a garden with structures and rocks creates an atmosphere conducive to self-examination. Waiting for a moment in the rest pavilion, at the bottom of the waterfall by the pool of water that gurgles and bubbles, the scent of the flowers permeates the air and you find a wonderful peace. After taking in the gardens, you move on, ready to engage the rest of the temple.

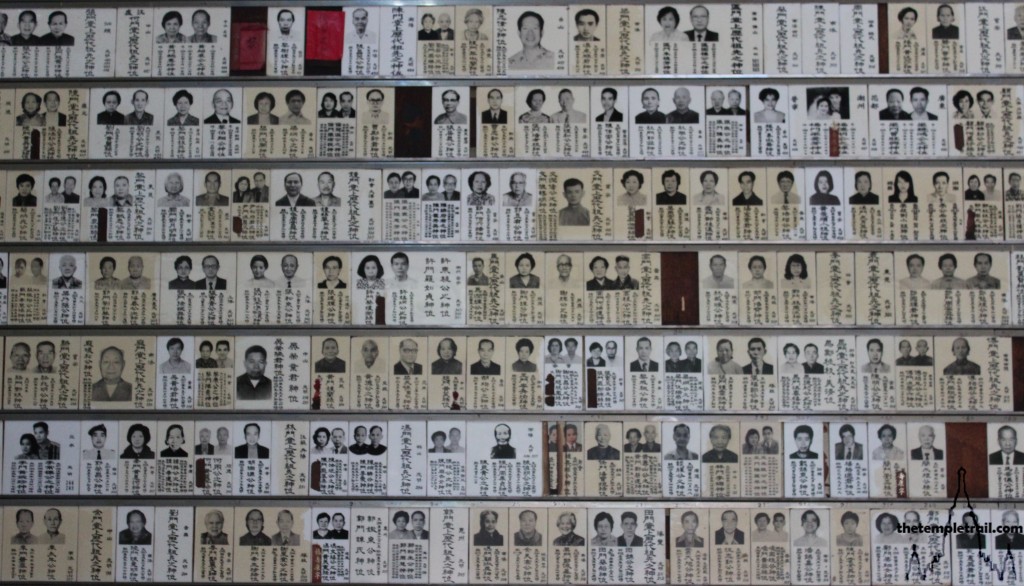

As you begin to walk towards the main buildings a large memorial archway (牌坊 páifāng) looms into view. Sometimes called a decorated archway (牌樓 páilou), these large, roofed symbolic gateways often mark the existence of religious spaces. To your left, on either side of the páifāng are large ancestor memorial halls. The first is larger and called Yek Fa Kung (翊化宮 Yì Huà Gōng), meaning ‘Assist Transformation Palace’ and the next is the Ching Wa Tong (清華堂 Qīng Huá Táng) or ‘Peaceful Magnificent Hall’. Even these two are not big enough to house all of the remains and close to the temple grounds is the large funeral complex called the Ching Chung Sin Yuen (青松仙院 Qīng Sōng Xiān Yuàn); Green Pine Court of Immortality. Looking into the halls, you see small white markers covering every wall. Each tablet has the names of the deceased and most have a photo. Behind each of them is a small compartment that contains the bone ash of the person. A quiet comes over you as you respectfully walk through the Yek Fa Kung. In the main foyer, you look upward to see a spiralling dragon descending from the ceiling. The three dimensional figure is reaching down from the clouds above. In the four corners, large bats are positioned to represent giving fortune.

In the powerful presence of these creatures, you imagine what the hall must be like during the Ching Ming Jit (清明節 Qīng Míng Jié) in April. The Clear Brightness Festival is more commonly known as Tomb Sweeping and is when people come to clean ancestor’s tombs and spend some time with them. Chinese people will often eat meals with their ancestors’ spirits present. While this seems somewhat morbid to the uninitiated, it is a joyous time when the family can get together. While the temple here is much fuller, with little space to sit down with the dead, rural Chinese will lay out a meal with places for those in the tombs and conduct complex rituals. Traditions vary throughout China, but the idea of spending time with the dead is universal. Leaving the presence of those who have passed on, you head to the main hall of the temple where the living worship other beings.

The temple has grown significantly over the years and as you get nearer to the main hall, you come closer to its origins. The temple was built by the Dragon Gate Sect, a group founded by Qiū Chǔjī (丘處機), a student of the famed teacher Wáng Chóngyáng (王重陽), founder of the Complete Reality School. Quán Zhēn Taoism began during the short-lived Jin Dynasty (1115 – 1234 CE). Wáng Chóngyáng was born to a wealthy family and was loyal to the Song rulers who had lost the north of China to the Jin. He took up a military and political career, but in 1159, at the age of 46 years old, he abandoned this to become a hermit and practice inner alchemy (內丹術 nèidān shù). On Zhongnan Mountain in Shaanxi Province, he made a dugout that he slept in for three years. While in a higher state of consciousness, he was visited by three immortals. Two of the Eight Immortals (八仙 Bāxiān), Zhōnglí Quán (鐘離權) and Lǚ Dòngbīn, and the alchemist Liú Hǎichán (劉海蟾). These three gave him secret rituals and instructions and after the encounter, Wáng believed he had passed back and forth through death. He took on students and taught them his ‘Complete Perfection’ method which incorporated his scholarly learning in Confucianism and Buddhism. He wrote the important Taoist text, the Record of the Immortals Encountered at Ganshui (甘水仙源錄 Gānshuǐ Xiānyuán Lù) which continued to be transmitted by his disciples.

Of his seven disciples, the Seven Perfect Ones of the North (北七真 Běiqī Zhēn), it was Qiū Chǔjī’s branch that prospered most and the Lóng Mén Pài is one of the most popular branches of Taoism today. The success of his branch is due to Qiū’s meeting with the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan. He was summoned by the Great Khan and travelled through the west of China all the way to the edge of the Mongol frontier in the Hindu Kush in 1222. The great Taoist work Record of the Perfected Chang Chun’s Travel to the West (長春真人西遊記 Cháng Chūn Zhēnrén Xī Yóu Jì) describes his meeting with the Khan. The work, which accords him his Taoist name Chángchūnzi (長春子), tells of how he impressed the Khan and his conversations with Ghengis Khan convinced the Mongol to spare the lives of the Chinese when he invaded China. When the second invasion of Jin territories came in 1232, the Khan was true to his word and the widespread slaughter that came with Mongol war did not happen. The influence of the sect was strong, but it was 11th generation successor of the Dragon Gate Sect, Mǐn Yīdé (閔一得), who secured the future of the then declining branch. Born in 1758, the priest promoted the Three Doctrines, combining Taoism with elements of Confucianism and Buddhism. Respected highly by many, he had many disciples and the Dragon Gate Sect grew throughout the later part of the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912 CE). Today it is the most widely practiced branch of Taoism.

Walking through complex, you come to the central temple axis. As you come to a huge páilóu, you turn right towards the front entrance to the compound. On either side of you in the courtyard after the páilóu are the small rest spots called the Rising Sun Pavilion (旭日亭 Xù Rì Tíng) and the Treasure Moon Pavilion (寶月亭 Bǎo Yuè Tíng). In the centre is a large eight trigrams (八卦 bā guà) with a diagram of supreme ultimate (太極圖 tài jí tú) representing yīn and yáng. This symbol is so iconic to Taoism and instantly recognisable to many non-Chinese as well. You pass a mosaic screen and enter into the first hall that is simply called Ching Chung Koon. Although it is not the oldest building of the complex, it carries the same name as the whole compound. Entering the large hall, you see murals of two Taoist protective spirits riding a lion and a Chinese unicorn (麒麟 qílín). To either side of the back of the hall are the sixty Tai Sui (太歲 Tài Suì), heavenly generals who take turns to look after the earth for a year in sixty year cycles. Walking to the front of the temple hall, you find two alters on either side of the front door. On the left hand side of the hall is Fuk Tak Kung (福德公 Fú Dé Gōng), an earth god of prosperity. On the right is a shrine for the Mun Gun (門官 Mén Guān), the Door Official. Passing another mural in the centre of the hall depicting Dau Mo (斗母 Dǒu Mǔ), the Pole Star and Goddess of Measure surrounded by the personified Twenty-eight Constellations (二十八宿 Èr Shí Bā Xiù) , you double back and exit using the door you entered by.

Crossing the courtyard once again, you find yourself standing before a set of steps that look up to the main hall. Climbing them you pass on either side of you the bell tower (鐘樓 zhōng lóu) and drum tower (鼓樓 gǔ lóu). At the top of the stairs you are met by a huge bronze cauldron (鼎 dǐng). Three dragons hold the lid of it aloft and on the side is written ‘Universe Purification’. Walking around the incense brazier and the pond that lies behind it, you climb more steps up to the platform in front of the main hall and a roofed area on it called the Mou Gik Yuk Dou Ting (無極玉道亭 Wú Jí Yù Dào Tíng), or Everlasting Jade Tao Pavilion. Three braziers on the platform and in front of them are four racks of the weapons of the Bāxiān and the main hall of the temple.

The Seun Yeung Din (純陽殿 Chún Yáng Diàn), or Pure Yang Hall, was the first building to be constructed on the site. Sometimes called the Palace of Pure Brightness, it is filled with incredible objects and, as you walk in through the right hand door, you are dazzled by the details. The fortune teller who is posted in the corner smiles at you and gestures you to go ahead and explore. After exchanging a few brief nods and words with the kindly soothsayer, you start to investigate the hall in more detail. There are three altars and the one you stand before on the right of the hall holds a statue of Wáng Chóngyáng, the patriarch of the Quán Zhēn Sect. Walking across the hall to the opposite side, you find a matching statue in the exact same style of Qiū Chǔjī, founder of the Lóng Mén Sect. The two statues are housed in brightly lit, elaborate shrines, as befits the two masters, but as you go back to the centre, it is the middle altar that draws your full attention. Two offering tables stand before it. On the table are various items, including a thousand year old jade seal. Flanking the offering tables are two goddess statues carved from Beijing white stone more than 300 years ago. These precious items, along with a pair of 200 year old lamps from the Forbidden City in Beijing, show the status of the temple’s main occupant. In his central position, Lǚ Dòngbīn gazes out at you with piercing eyes set in a thin face. He sits between two attendants, one of which carries his sword which gives him the ability to be invisible in the sky.

Lǚ Dòngbīn is one of the great immortals of Taoism. Said to have been born in 796 CE during the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE), the scholar became one of the Bāxiān. Also known as Pure Yang Master (純陽字 Chúnyángzǐ), he is called Lu Chun Yang, but when you talk to the fortune teller and temple keeper at the entrance to the hall, they call him Patriarch Lü (呂祖 Lǚ Zǔ). This is common among the followers of the Dragon Gate Sect. As a young man, he was an excellent academic, but his life changed when he experienced the Dream of the Yellow Millet (黃粱夢 Huáng Liáng Mèng). While cooking millet, he had a dream of success in the Imperial Examination (科舉 Kējǔ), followed by a successful political career and marriage. In the dream, everything suddenly collapsed and he lost his government office, his wife betrayed him and his children were killed. Each character in his dream was played by the immortal Zhōnglí Quán. He awoke from his dream and followed the ancient immortal to study and cultivate the Tao (道 Dào). Lǚ Dòngbīn was then put through ten trials by his new immortal teacher. The Ten Trials of Patriarch Lü (十試呂祖 Shí Shì Lǚ Zǔ) records the acts that earned Lǚ his immortality due to his perfection of character and purity. He became one of the Bāxiān, albeit an imperfect one as he was a drinker and a ladies man who was prone to the occasional bout of anger. He is a popular figure concerned with the Taoist sexual practices (房中術 fáng zhōng shù) and the story of his amorous encounters with the famous courtesan, and later goddess, White Peony (白牡丹 Bái Mǔdan) is well known among Chinese people.

Looking at the gaunt statue of the immortal, you see little of the bawdy side of his character. He seems quite austere. Leaving his presence, you exit the hall and peer in at a ceremony taking place in the Wan Shui Tong (雲水堂 Yún Shuǐ Táng) or Hall of Cloud and Water. The hall is fairly spartan, but some nice modern calligraphy adorns it. The decorations play second fiddle to a Taoist ceremony that is taking place inside. As it appears to be a family funerary ritual, you do not enter the hall and disturb proceedings. Instead you head back through the complex, past the ancestor memorial halls and through an unusual octagonal gate. As you once more view the bonsai lining the back entrance, you attempt to unravel the complex nature of the temple. Much like Taoism itself, there are many things to learn. The Way is not easy to navigate, just like the imagery in Ching Chung Koon. The bonsai trees remind you of the trunk of Taoism with its many branches. While all a little different, they belong to the same tree. The expansive tree of the Tao, which, at Ching Chung Koon, attracts the souls of the ancestors in order that they may be transformed as the immortals were before them.

Taipei Confucius Temple

Taipei Confucius Temple