The ancient city of Kaifeng has rewarded you with many interesting sights. The Temple of the Chief Minister and the Iron Pagoda are well known, but the old capital has other intrigues that lie just off the radar. Places like the Fan Pagoda and the Music Pavilion dedicated to the legendary emperor Yu the Great (大禹 Dà Yǔ), founder of Xia Dynasty, have been deserted, allowing you to have had free rein over them. You pass a busy shop window and the smell of fresh nang bread emanating from it snares you. Hot bread in hand, you walk along the tumbledown streets towards your next destination. Ahead of you, a lake blocks your direct route and you begin to circle it. Built in the lake, but connected to the far bank, is the object of your wanderings. As you come to the other side of Lord Bao Lake (包公湖 Bāo Gōng Hú), you stand at the entrance to the unique Bāo Gōng Cí (包公祠), the ancestral hall and temple of Bāo Gōng (包公), the famous incorruptible magistrate of the Northern Song Dynasty (959 – 1126 CE).

Given the honorific title of lord (公 gōng) posthumously, he was born Bāo Zhěng (包拯) into a family of scholars in Anhui Province in 999 CE. His family were not wealthy and he was brought up alongside the poor people of China. Despite being able to afford education, he felt deep sympathy for the lower classes of society and despised the corruption that was rife among those in administrative positions. Aged 29 he passed the Imperial Examination (科舉 Kējǔ) with the rank of Advanced Scholar (進士 Jìnshì), the highest normal level. His rank determined that he could have a high position, but he chose not to take up a governing role so he could take care of his parents. Ten years later, he was assigned the position of magistrate (判官 pàn guān) in Tianchang county.

A magistrate was a tough position to be in as local interests could destroy your career if you annoyed the wrong people in power. Bāo Zhěng, however, excelled in the role and was seen as being righteous and wise. He fearlessly made decisions based on morality and his fame spread throughout the land until he was noticed by the Emperor Renzong (宋仁宗 Sòng Rénzōng). He rose through the ranks until he was made an Investigating Censor (監察御史 Jiānchá Yùshǐ). In this role, he reported directly to the emperor and it is where he gained his strongest reputation for fearlessly pursuing corrupt officials, regardless of their rank. The emperor listened and to his reports and acted on his impeachments. He took down more than 30 high ranking officials throughout his career and did not meet with a nasty end like so many other Jiānchá Yùshǐ.

Due to his aggressive pursuit of corruption, he lasted as Censor for only a couple of years, before being removed from the capital and then brought back with the role of Vice-Minister of Ceremony in the Ministry of Rites (禮部 Lĭ Bù). This position rendered him ineffective against state corruption. He regained some powers later and in 1057, he was made the magistrate of Bian (Kaifeng). He only served for a year, but introduced many reforms that were popular with the people. He died in 1062 and was buried in Anhui. Bāo Gōng Cí was originally built in 1066, just four years after his death and his legend continued to grow until his was deified. Temples to Bāo Gōng can be found throughout the Chinese sphere of influence and his image is often found next to the main image in temples to other deities.

Magistrates, the lowest rung on the bureaucratic ladder, were often portrayed by the people as corrupt and greedy, but Bāo Zhěng was given the nickname Clear Sky Bao (包青天 Bāo Qīng Tiān), in reference to his upright and honourable nature. He was seen as honest in his duties of collecting taxes, registering land, assessing families and deciding disputes. When the people deified him after his death, they were making a clear statement that they believed in justice and had contempt for corruption. He is usually depicted in opera and art as being black-faced as a symbol of his impartiality.

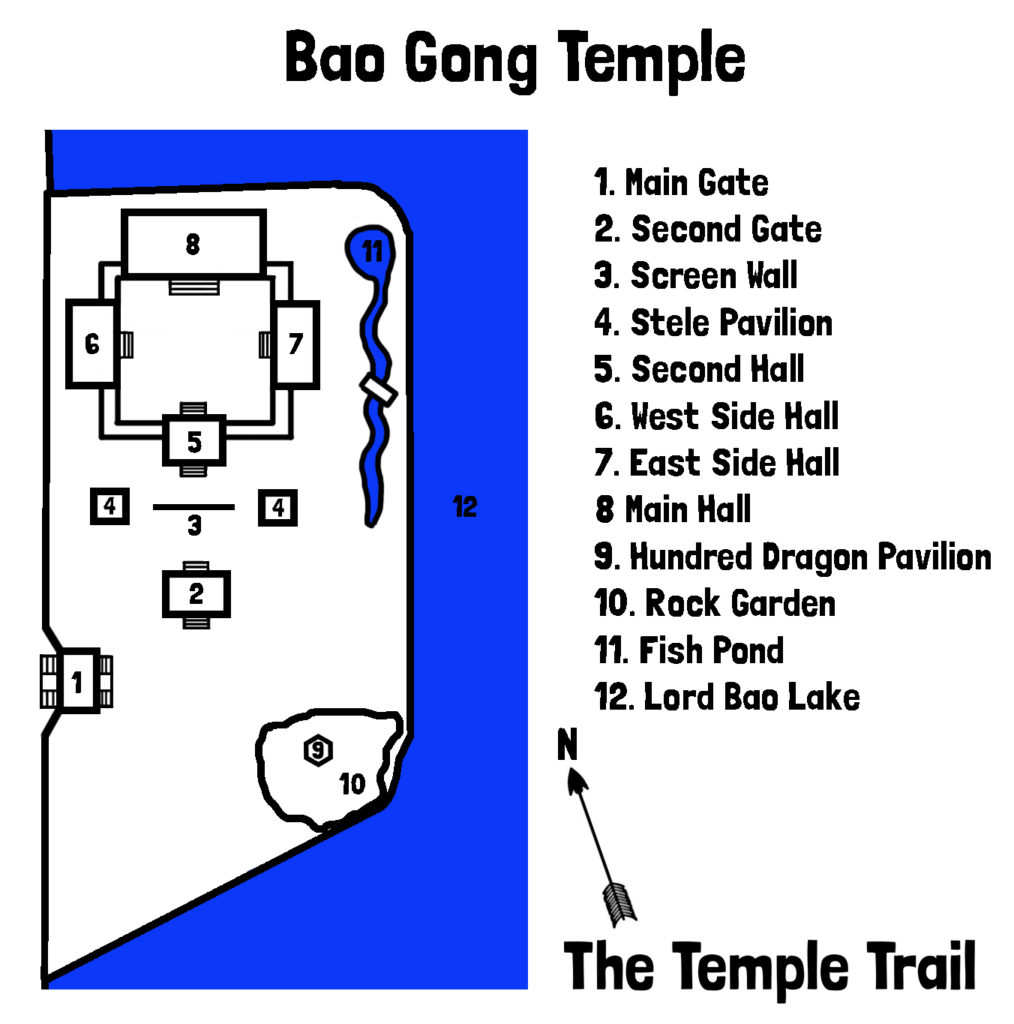

Arriving at the Main Gate, you pass through the colourful, yet authoritative looking structure. The building seems like the perfect introduction to the temple of the Iron-faced Magistrate (鐵面判官 Tiě Miàn Pàn Guān). The strong looking structure is highlighted by bright paintwork, reflecting the serious, yet interesting nature of the magistrate. Exiting on the other side of the gates, you are now on the small islet of the temple compound. Following the path, you next encounter the more conservative Second Gate. This marks the threshold of the memorial complex proper and pressing on through it, you stand in front of the screen wall (照壁 zhàobì) that stops evil entering the temple buildings.

All around you are colourful displays of chrysanthemums, flowers that the area is famous for. The chrysanthemum (菊花 jú huā) is culturally, a very important flower in China. Cultivated since the 15th century BCE, it is one of the Four Gentlemen (四君子Sì Jūnzi) along with plum blossom, bamboo and orchids. These four are the noblest plants in Chinese culture and are the subject of many paintings, each of them representing a season. Chrysanthemum is the autumnal flower and was so honoured, that in antiquity, only the nobility were allowed to cultivate it. The name itself allows many plays on words and jú (菊) sounds like jū (居), meaning to remain or reside. It also sounds like jiǔ (久), meaning long time, therefore aligning the flower with long life. As it can withstand cold climates, Chinese scholars said it symbolised the virtues of a man who could maintain his grace against hardships. The presence of the flower here is apt, considering that the man honoured was the quintessence of the honest and upright official (清官 qīng guān).

Taking in the beautiful blossoms, you pass the eastern and western Stele Pavilions (碑亭 Bēi Tíng) on either side of you, before moving towards the Second Hall (二殿 Èr Diàn). The pavilions each house large stone tablets, but more impressive, is the one housed in the Second Hall. There are various artefacts in the hall, including some poetry and calligraphy that was written by Bāo Zhěng. The stele in the centre of the hall is a substantial historical piece called the Kaifeng Residence and Office Monument Inscription. It is a record of public officials and positions from the Northern Song Dynasty and Bāo Zhěng’s name appears on it. His name has deeper carved grooves than the other names, showing how over the generations, the good magistrate has been continually remembered.

Leaving the hall, you exit into a courtyard filled with more of the beautiful chrysanthemums. He sun glints off the East Side Hall as it descends closer to the horizon. The West Side Hall interests you most and you enter it to see the waxwork scene that recreates one of the most famous cases of Bāo Zhěng. There are many stories of the magistrate’s deeds that have been made into operas and television shows, but one of the best known is that of Chén Shìmĕi (陳世美), the unfaithful and heartless husband. The Beijing Opera story relates that Chén Shìmĕi placed first in the Kējǔ and was adopted as the son-in-law of the emperor. Chén Shìmĕi had a wife and children in the provinces, and when they came to find him, he pretended that he did not know them. He then sent his servant to murder them. The servant could not do and instead killed himself. Chén Shìmĕi’s wife then went to Bāo Zhěng who promptly took action by having him executed. The Empress Dowager came to try and stop him, but Bāo had him beheaded regardless. After taking in the tableau, you leave with a respect for the judge.

The stories of Bāo Zhěng are legendary, but one interesting association to come from them is that he is often connected to Yama, King of Hell (閻羅王Yán Luó Wáng) and the Infernal Bureaucracy. He is now able to judge affairs in the afterlife as well as those of the living. People appeal to him for justice on behalf of themselves and their deceased relatives. Often he is depicted with his two servants; Zhǎn Zhāo (展昭), a knight-errant (遊俠 yóuxiá), and Gōngsūn Cè, an intellectual and secretary to Bāo Zhěng. Gōngsūn Cè (公孫策) is said to have invented the novel execution devices employed by the magistrate.

Back in the courtyard, you head for the Main Hall (大殿Dà Diàn). Entering the hall, you are immediately struck by the dark presence of a large bronze statue. To the right of the statue are examples of the devices created by Gōngsūn Cè. The three bronze choppers were used for beheadings of different levels of people. The dog head lever-knife (狗頭鍘 gǒu tóu zhá) was used on commoners, the tiger head lever-knife (虎頭鍘 hǔ tóu zhá) on government officials and the dragon head lever-knife (龍頭鍘 lóng tóu zhá) on royalty. All around the hall are tile murals of some of the stories about Bāo Zhěng, but the statue itself is what dominates the hall. The black bronze depicts him on a seat wearing the official black hat with stiff long wing-flaps of the Song Dynasty. One hand holds the arm rest, while the other is clenched showing his iron will and determination.

Taking your leave from the magistrate, you exit to the rockery and fish pond that is located to the east of the temple buildings. Following a path through the beautiful rocks, you pass a statue of two herons, fish in talons, standing astride a tortoise. Herons have two meanings in Chinese culture; ‘path’ or ‘way’ and also wealth. The tortoise represents longevity, strength and endurance. Observing the symbol laden statue, you walk on to the Hundred Dragon Pavilion (百龍亭 Bǎi Lóng Tíng).

This open air pavilion sits atop a stone hill which you climb using the zig-zagging staircase. The sun is rapidly nearing the horizon and you take a few moments to look over the complex and the lake while the light illuminates it softly. Despite not wanting any kind of special favour during his lifetime, you feel that Bāo Gōng would appreciate the loyalty of the Chinese people were he around today. While much of the legend is just that, Bāo Zhěng made a big enough impact in his lifetime to be remembered and worshipped to this day, almost a thousand years after his death. Here, in his ancestral hall, he is celebrated by the descendants of those he ruled for and against a millennia ago.

Tam Kung Temple, Shau Kei Wan

Tam Kung Temple, Shau Kei Wan