The MTR exit spits you out onto a nondescript road on the eastern side of Hong Kong Island. Walking under the overpass, you cross the road and go by a public bathing facility. This hangover from the days before internal plumbing lets you know that you are in an old residential neighbourhood. Shau Kei Wan was once a fishing village, like many others in the territory, but now it is a mass of tower blocks and homes built in the second half of the twentieth century. Entering a pedestrian subway, you burst out into the light near the old shoreline. Here, you spy the single-storey building that stands out from the rest. The grey bricks and ornate roof of Tam Kung Temple are as far from the modern buildings as the neighbourhood is from its former self.

Tam Kung Temple was built in 1905 by fishermen who used to moor their boats in Shau Kei Wan bay. Tam Kung is a sea deity, so he looked after the fishermen as they ventured into the oceans. The building you are looking at has been renovated a number of times and this current incarnation was remodelled in 2002. The boy god Tam Kung (譚公 Tán Gōng) is an interesting character and he is a very local god, his worship being found only within the coastal area between Hong Kong and Macau. Officially deified during the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912 CE), there are a number of accounts of the god’s origins. The official account from the Chinese Temples Committee is that he was a native of Huizhou in Guangdong during the Yuan Dynasty (1271 – 1368 CE) and that he was worshipped from the age of 12 due to his abilities to cure the sick and to control the wind and rains. It was said that he could throw a cup of peas into the air and stop storms, or throw a cup of water to start rain. He is said to have lived until old age, but maintained the face of a 12 year old. Stories tell of him wandering the mountains with a tiger carrying his possessions. There is an ancestral temple to Tam Kung on Nine Dragon Peak (九龍山 Jiǔ Lóng Shān) in Huizhou that has been there since at least 1824, and longer that that according to the temple stele. If the stone inscription from 1824 is to be believed, a temple to Tam Kung has been there for “thousands of years”, making the Yuan dynasty date incorrect. Regardless of the date, people from the Huizhou region are particularly devoted to Tam Kung and the ancestral temple there is older than any other, including the Macau temple built in 1862.

Another account tells of him being an important local from Wei Yang, a Hakka settlement in Guangdong. It says that he became enlightened in Kowloon and gained power from the remains of the nine dragons that make Kowloon’s northern boundary. There is also a controversial, but compelling story about Tam Kung put forward by amateur Sinologist Jonathan Chamberlain, that uses Kowloon as the origin of Tam Kung. He thinks that the origins of the god lie in the last emperor of the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 CE). The advancing Mongols of Kublai Khan sacked the Song capital of Hangzhou in 1276, capturing the young Emperor Gong of Song (宋恭帝 Sòng Gōng Dì) and taking him to their capital, Khanbaliq (Beijing). Upon his abdication and removal, he was assimilated into the Yuan court as the Duke of Ying. The Song resistance needed a new figurehead and the younger brother of Gong, Emperor Duanzong (宋端宗 Sòng Duānzōng) was enthroned. The court of Song fled to what is now Hong Kong and they set up in Kowloon. It is said that the area, is named because the young emperor counted the eight hills of the area and said that eight dragons were present. An advisor pointed out that as he was emperor, there in fact nine dragons present, giving the area the name Gau Lung (九龍 Jiǔ Lóng), meaning “nine dragons”, eventually corrupted by the British to Kowloon. Until it was levelled during the Japanese occupation, there was a sacred hill in Kowloon called Sung Wong Toi (宋王臺 Sòng Wáng Tái) – Terrace of the Sung Kings. The inscription on stone that was once part of the hill is all that remains today.

Duanzong died of sickness in 1278, aged only ten years old in Meiyu, Gangzhou (now Silvermine Bay, Lantau Island) after fleeing once more from the Mongols. The youngest brother, Emperor Bing of Song (宋帝昺 Sòng Dì Bǐng), ascended the throne aged just eight. The boy ruled for only ten months and following the naval Battle of Yamen, that saw the Song forces finally beaten by the Mongols, his retainer Luk Sau Fu (陸秀夫 Lù Xiùfū) picked up the boy emperor and jumped off a cliff with him, committing suicide rather than accepting capture. Chamberlain also believes that Luk Sau Fu became Hau Wong, another god worshipped in Hong Kong. Hau Wong is often associated with Bing’s bodyguard Joeng Loeng Zit (楊亮節 Yáng Liàng Jié), giving weight to the idea that Tam Kung could be Bing.

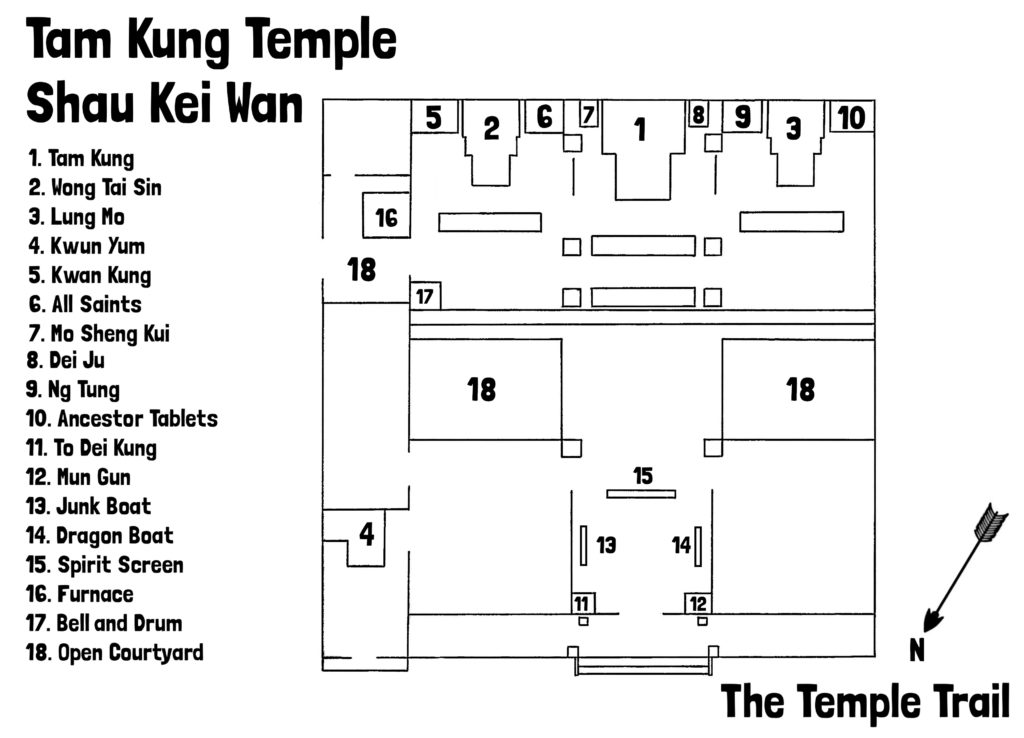

Walking to the entrance of the temple, you turn on your heels and look downwards at a stone on the ground just behind you. In front of it is a pot filled with joss sticks. This rock is said to be Tam Kung’s magic seal. Twisting away from the magical place, you gaze up at the ornate roof and entrance to the temple itself. To the left of the doorway, a homeless man sleeps. This temple has drawn him with its protective properties. The god is popular with the needy and the sick; in the 1960s he is said to have helped the people of Shau Kei Wan during a rampant cholera epidemic. Entering under the gold characters of the lintel, you find yourself in a surprisingly light space. Hong Kong temples are normally fairly dark in nature, but this building is airy and has the natural light coming in strongly. The temple is said to have outstanding fung seoi (風水 fēng shuǐ), as it is built on the front of a dragon whose geomantic vitality reaches across to Kowloon. It is well orientated with its back to a hill and front facing water. This fung seoi is evident in the well thought out structure you have entered. Passing the Mun Gun (門官 Mén Guān), Door Official, and To Dei Kung (土地公 Tǔ Dì Gōng), the Earth God, on either side of the entrance, you discover a wonderful model dragon boat and one of a junk in the small foyer. After inspecting them, you go through the dong chung (擋中 dǎng zhōng) spirit screen doors and into the main courtyard and hall area.

The space seems very large and the inner part of the temple looks much bigger than the exterior walls would suggest. Directly ahead of you, in the centre of the hall behind three rows of offering tables, Tam Kung looks out over his abode. Before going to meet the god face-to-face, you make your way to the left of the main hall to the altar on that side. In front of the deities here, an intricate offering table is decorated with a painted relief of the Baat Sin (八仙 Bā Xiān), or Eight Immortals of Taoism. The altar itself has three shrines, or houses. To your left a circular door leads to an incinerator area and, after gazing briefly through it, you close in on the altar. On the left is Kwan Kung (關公 Guān Gōng), the god of war and on right, All Saints, a collection of many gods, is represented.

The central house is home to Wong Tai Sin (黃大仙 Huáng Dàxian), a god with immense popularity in Hong Kong. The area of Kowloon named after him has an enormous Wong Tai Sin Temple as the focus of the district. The Great Immortal Wong is famed as a healer and god of medicine. Born in the 4th century CE in Zhejiang Province, he is said to have been a shepherd who met an immortal on Red Pine Mountain when he was 15 years old. He later gained immortality and was able to transform rocks into sheep. He became known as the Red Pine Immortal and lived as a hermit on the mountain until his death. He was brought to Hong Kong in 1915 by Leung Renyan, a herbalist, where his cult took off rapidly.

Walking to the centre of the hall, you stand before the main altar, again divided into three parts. To the left and at ground level, the ha tan (下壇 xià tán), or lower altar, is a higgledy-piggledy space filled with various images including Baak Fu (白虎 Bái Hǔ), the White Tiger and Shun Fung Yi (順風耳 Shùnfēng Ěr), Favourable Wind Ears. The main image here is the rustic looking statue of Mou Soeng Gwai (無常鬼 Wú Cháng Guǐ), the Unpredictable Ghost. The area is lit in moody red light, as is the opposite side of the altar at ground level. This holds a tablet for Dei Ju (地主 Dì Zhǔ), a manifestation of the earth god. Above this is a surface that is exposed fully to the daylight. Here a set of ceramic Fuk Luk Sau (福祿壽 Fú Lù Shòu) figures are placed. These three gods are personifications of happiness, prosperity and longevity.

The main part of the altar is the home of the baby-faced main deity of the temple. Tam Kung, dressed in a red nine-dragon robe, a symbol of imperial power in ancient China. This fits in with the theory that he was a boy emperor. Although he is not holding a bell, his common iconography normally puts one in his hand. A bell is a symbol of military power, as it was used in ancient times to put troops into formations. In front of him are three wooden images of the god. They are all fresh-faced and have their hair styled as a child would. These images are all older than the main image and draw your attention.

With health being a definite theme, with Wong Tai Sin on the left and Tam Kung in the centre, you move on to inspect the altar on the right and find who is presiding over Eastern section of the temple. The three-part altar holds a curious set of gods in the shrine on the left. Four statues form a quincunx around a larger central one. These five figures are the Ng Tung (五通 Wǔ Tōng), the Gods of Five Lucks. Ng Fuk (五福 Wǔ Fú), Five Lucks, is ingrained into Chinese culture. These lucks are longevity (長壽 cháng shòu), riches and honour (富貴 fù guì), health and peace (康寧 kāng níng), good morals (好德 hǎo dé) and virtuous death (善终 shàn zhōng). It is quiet unusual to see the five lucks represented as gods as they are normally symbolised by five bats.

In the central position is Lung Mo (龍母 Lóng Mǔ), the Dragon Mother. Born in Guangxi over 2000 years ago, she is the goddess of motherly love. In her lifetime, she raised five dragons and became loved by the people of her region. Her main temple in Hong Kong is on Peng Chau Island, but her inclusion here is not necessarily related to her motherly aspect. Looking into the face of the goddess, you consider that dragons have control over the rains and so does Tam Kung; an imperial ‘dragon’. So perhaps she is here due to a link that has formed between the young rain god and the Mother of Dragons. It all adds up if you consider the powers of the two cross over in regard to protection and control over the weather. The statue before you is quite natural looking and Lung Mo too wears a dragon robe. Next to her on the right are ancestor tablets of important people related to the temple. These select few are looked after by the Dragon Mother and are given plenty of offerings in their prominent position in the temple.

Before stepping out of the chamber, you look back at the three main altars. You can see a natural link between the deities. Wong Tai Sin and Tam Kung are both healers, but the boy god also shares his rain powers with Lung Mo. Going past the elderly temple keeper, you enter a small hall on the far left corner of the temple. Upon arriving in the room, you see two statues of Kwun Yum (觀音 Guānyīn), the bodhisattva of Mercy. Often incorporated into Shenist and Taoist temples, Kwun Yum started as a male Buddhist bodhisattva called Avalokiteśvara. The female element came to the fore in China about a thousand years ago and she was co-opted by the Taoists and followers of Shenism (Chinese folk religion) due to her pervasion into the Chinese cultural sphere. The goddess and bodhisattva is profoundly iconic and tied to the Chinese religious arena in a Gordian fashion. Here, both visions of Kwun Yum seem to be represented, as if to cover all bases. The main statue is a dark lacquered wooden one and seems to project the Taoist and folk religion ideals, whereas the other, lighter statue is definitely in the Buddhist aspect with the Buddha Amitabha on her crown. After a few moments in this room of compassion, you head back through the temple and out to the front.

At the front of the temple, you look again at the sleeping pilgrim. He has been drawn to the temple as a haven of protection. He will get no actual food or money here, but he will get a brief period of shelter under the temple’s eaves. What he will get is spiritual reassurance. If he is lucky, the gods will shine down their blessings upon him and grant him a small reprieve from his misfortunes. Before leaving, you drop a few dollars next to his belongings. The temple is a window into how real people can be deified in Chinese culture. A shepherd, a country girl and a child emperor can all become gods in Hong Kong.

Xochitécatl

Xochitécatl