The feeling of festival is in the mid-autumn air. Flags and banners adorn the streets in the small neighbourhood of Tai Hang on Hong Kong Island in preparation of the imminent event. Once a village, Tai Hang retains much of its old nature. Despite the towering apartment blocks, it is still laid out on a small grid that has street names reflecting its past. On School Street, there is an old school building from colonial times. The narrow streets are now lined with bakeries and restaurants, but are still filled with ancient residents who have seen the area grow over the years. Stopping in one little bakery, you try a small ‘wife cake’. The warm pastry gives way to a sweet paste of almonds and winter melon. Chewing on your snack you head down Lily Street to your destination: Lin Fa Kung (蓮花宮 Lián Huā Gōng), the Lotus Flower Palace.

In the village of Tai Hang there was large boulder called Lotus Rock. Reports of appearances by the goddess Kwun Yum (觀音 Guānyīn) sparked the locals to revere the place. Kwun Yum, a form of the male bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara ( 觀世音 Guānshìyīn), was fully recognised as a Taoist goddess during the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE) and has been popular throughout the Chinese sphere of influence ever since. As she is the goddess of mercy, her materialisations here were taken as good omens of protection and fortune, so a formal temple was seen as a way to harness the goddess’ blessing. The first structure on the site was built in 1846, four years after the British were formally ceded the island, and would have been very simple in design; not much more than a shrine. The current structure, which ensheathes Lotus Rock entirely, was originally built in 1863 and has been renovated twice in the twentieth century. The name is not entirely uncommon for a Kwun Yum temple and is linked to the idea that the goddess learnt Taoist teachings from lotus petals. Her temples often feature motifs of water and the moon symbolising detachment and tranquillity. Despite her status as the goddess of mercy, the temple sees a lot of footfall on the 26th day of the lunar month as it is the Open Treasury day. Worshippers come to borrow prosperity from her so that they become financially secure.

The temple is architecturally intriguing and unique in its construction. Approaching it from the front, you see that the temple has an unusual half-octagonal shaped façade. Also, though it is now covered by the new higher-level road, the temple is supported by pillars and actually has a faux lower level. The building appears much taller in old photos. Taking in the exterior, the grey bricked building is capped with an ornate roof and has a semi-circular balcony at the front. To either side of the balcony are decorative windows that are framed by a pair of deoi lyun rhyming couplets (對聯 duì lián). The couplets glorify Kwun Yum and are each in a strange fruit shape. They descend from reliefs of branches that rest along the top of the windows. The window on the left’s branches bear peaches, and the one on the right pomegranates. Peaches symbolise longevity and pomegranates fertility. The balcony itself has two sets of couplets and a pair of birds symbolic of elegance and grace.

After viewing the exterior, you climb the steps on the right to see inside. Going past an inscribed tablet that represents a Mun Gun (門官 Mén Guān) door official, you stand before the open doors of the temple. From each door, a stern face sizes you up. Having passed the door official, you now have to be judged by the two gate gods. On one door is Chen Shuk Bo (秦叔寶 Qín Shūbao), the white-faced god who brandishes a mace. On the other is Wat Chi King Tak (尉遲敬德 Yuchi Jìngdé), the black-faced god. The two were both historical generals of the Tang Dynasty. Their feats of bravery gained them reverence to the point that they were absorbed into Chinese folk religion as the gate gods. Shenism, the folk religion, is a form of ancestor worship that often takes historical figures and turns them into gods. A famous example of this is the Three Kingdoms Period general Guān Yǔ (關羽), who is now one of the most popular figures of worship throughout East Asia.

Passing the door sentinels, you now stand under the octagonal roof. Looking up at the ceiling, you are captivated by a magnificent golden dragon that circles it. The coiling dragon is a sign that the temple is home to the famed Tai Hang Fire Dragon. In 1880, Tai Hang, still a Hakka village, was the location of a plague. One stormy night a villager killed a snake, but the next day, the body had disappeared. Within days, a plague was wreaking havoc on the small village. After many had already died, a village elder had a vision of the Buddha in his dream. He was instructed to perform a ritual fire dragon dance and light fire crackers during the Mid-Autumn Festival. This, he and the other villagers did and the sulphurous fire crackers drove away the plague. Every year since then, the ritual has been performed to drive away sickness from the area. For three nights of the festival, the dragon goes to the temple and the incense sticks that line the rope beast are lit before it flies through the streets. The image readies you for the coming dragon.

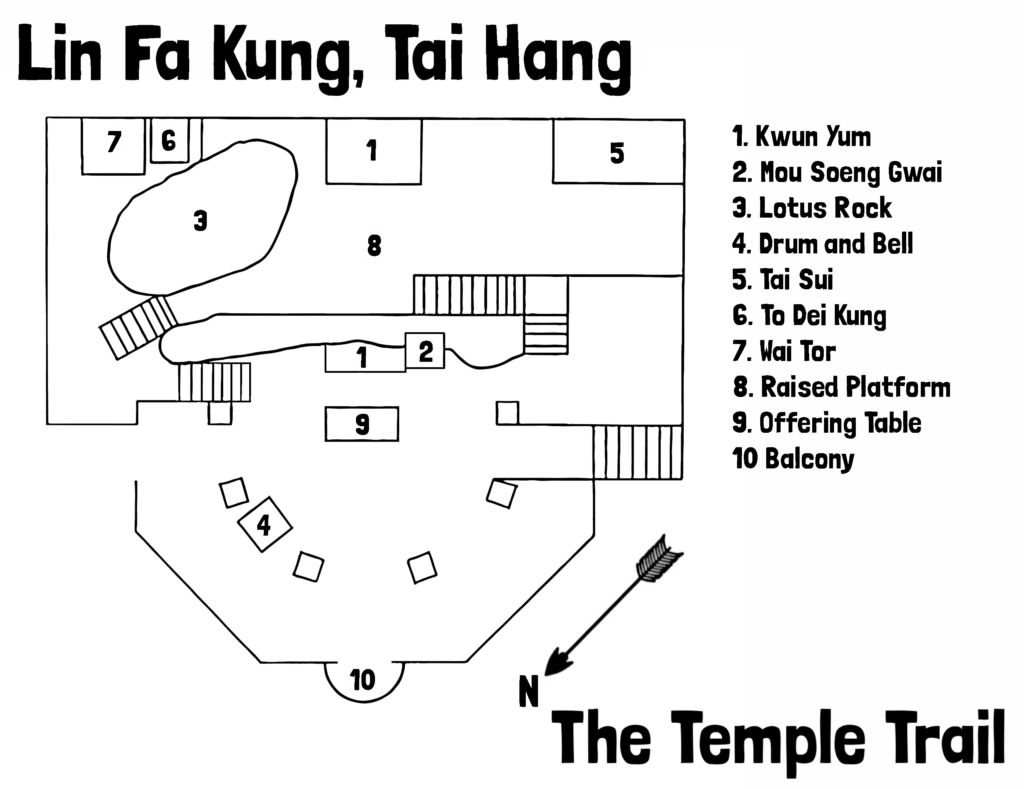

Walking around the offering table in the middle of the room, you look out of the balcony at the new developments all around the sacred space. New concrete buildings block your view of the sea that lies just a few hundred metres away. Turning around you see the whole of the temple ahead of you. It is on two levels in an open plan. Lotus Rock is the foundation on which the temple is built and in front of it is the first altar to Kwun Yum.

The stone altar is fabulously carved with dragons, phoenixes and bamboo. In the centre, swaddled in red cloth is the goddess herself. The gold visage peeks out at the worshippers who beseech her for luck. Here, she has a clear view out of the balcony bay at the constantly changing skyline. Next to her is the slender standing statue of a figure locals sometimes refer to as Yim Choi Sun (陰財神 Yīn Cái Shén), the “Yin God of Wealth”, adorned with garlands of symbolic paper money. He is not the normal smiling Choi Sun, but is the netherworld wealth deity. He is often referred to as Mou Soeng Gwai (無常鬼 Wú Cháng Guǐ), the Unpredictable Ghost. His tongue sticks out of his mouth on his gaunt, sad-looking face. He is one of the hell spirits known as General Xie (謝將Xiè Jiàng), the Catching Lord. His hat has the words yat kin fat choi (一見發財 yī jiàn fā cái), get rich at one sight, emblazoned on it. The imagery of the two gods seem to have been intertwined here. Looking at the mournful image, you can see that this god deals with money for the dead, rather than for the living.

Mou Soeng Gwai is one of a pair of gods along with General Fan (范將 Fàn Jiàng), a small black figure who punishes the wicked deceased. General Xie, rewards the virtuous dead. In life, the two generals were magistrates in Fuzhou. One day, they were on their official rounds when a storm hit. When they reached a bridge, Fan told Xie to go and get umbrellas and meet him back on the bridge. On his return, Xie got stomach pains and had to rest. As the rain fell, the river flooded, but Fan stayed put waiting for Xie. The river swept him away and he drowned, turning his face black. When Xie arrived and found his friend dead, he hanged himself from a tree and his tongue hung out from his mouth. After their death, they became the Black and White Guards of Impermanence.

To the right of Mou Soeng Gwai a set of stairs takes you to the platform above the altars. From here you look at the rafters of the temple. They are moodily lit and swathed in joss smoke. The darkness and light play against each other, giving the space a mysterious air. Turning around, you head for the right hand corner of the platform. Here, an altar that looks like a set of shelves is lined with four rows of ceramic statues. The small, brightly-painted figurines are the Tai Sui (太歲 Tàisuì). These sixty are the gods of the year. The heavenly generals are time gods that correspond to stars opposite the planet Jupiter. According to the Chinese zodiac system, for each year, one of the military gods is influential on behalf of the Jade Emperor. They can be fortunate or unfortunate for you and are loaded with symbolism. Preferring not to get involved in their machinations, you retreat to the centre of the platform.

In the middle, directly above the lower altar, is another to Kwun Yum. The rustic golden statue is housed in a carved wooden altar and seated on a throne, shrouded in silk. The image is simple and completely gold painted with no details picked out in more realistic colours. Below her, on an offering table is a sea of pink lotus-shaped lamps. The faithful donate them to the temple so that fortune will pour onto them. The temple stores hundreds of these lamps, but only a fraction are on display to please the goddess. To your left is the top of Lotus Rock. The rock is the foundation for the wooden superstructure that covers it like the sea does an iceberg. The tip of the boulder remains exposed so as to retain the original significance of the site.

You take the flight of stairs that circle the rock and step down to a mezzanine platform. In this corner of the temple a small altar containing a statue of Wai Tor (韋馱 Wéituó) sits behind the great stone. Wai Tor is a Buddhist deva and the guardian of the dharma. His presence here is a reflection of the cross-over between Chinese faiths. He is dressed in armour, as is usual, and has cultural links to the Hindu war god Murugan and the bodhisattva Vajrapāṇi. Reflecting this military background, he is surrounded by other warlike figures. His retinue includes a statue of Kwan Kung (關公 Guān Gōng), also a dharma protector and Na Cha (哪吒 Nézhā). Na Cha, the Third Lotus Prince, is a Taoist protection god and is particularly worshipped in Macau, where a small temple dedicated to his sits in the centre of the old town. He is also featured in the novel Investiture of the Gods (封神演義 Fēngshén Yǎnyì) and Wú Chéng’ēn’s famous classic, Journey to the West (西遊記 Xī Yóu Jì). Riding his ‘flaming wind wheels’, he is always depicted as a child. Next to this busy little altar is a small one to To Dei Kung (土地公 Tǔ Dì Gōng), the Earth God.

Descending the final set of stairs, you exit the temple, making a note to return in the evening a few days later. The days pass quickly and as night falls, you revisit the former village of Tai Hang. The rhythmic pounding of Chinese drums directs you toward a small alley by the local community centre. At the front of the alleyway, the head of the dragon awaits its body. The Rope construction has metal teeth and torches for eyes. He truly is a fearsome looking creature.

From his horns hang paper talismans (符 fú) and ribbons. The master of ceremonies stands in front of the dragon between two pomelos on sticks that are the dragon pearls. He lights incense and prays as the 67 metre-long rope body is affixed to the head. In a heartbeat the dragon comes to life. Its 32 sections are carried by young local men and, suddenly, it takes to the air and flies through the streets. Struggling to keep up, you follow the crowds until you hit a wall of people. After entering the temple for a while, the dragon re-emerges with thousands lit joss-sticks covering its body. The fiery beast soars down the streets amid lanterns and drums and clouds of smoke follow in its wake as it cleanses the area of malodour. Standing in the crowd, you sense the roar of the fire dragon in flight and feel purged of illness.

St John’s Co-Cathedral

St John’s Co-Cathedral