Walking the temple lined streets of the northern Laotian city Luang Prabang, you are enthralled by the complex history of the area. Lao ladies crouch by the roadside serving steaming bowls of noodles heaped with herbs and peanuts. Behind them are swanky cafes that deal in French coffee and patisserie concoctions that owe their popularity to the colonial overlords that once held the reins of Indochina. Luang Prabang was a protectorate under the French and the palace of the former kings of the area still captivates visitors. The heritage at Luang Prabang is deep enough to bathe in and was spared the renewal that was brought about by the communist Pathet Lao in the mid-1970s. There are so many temples in Luang Prabang, you are choking on them. Your eyes dart excitedly all over the place, unable to focus on one spot. Walking up Sisavangvong Road in the centre of the peninsula, to the right lies the former palace, but your left is dominated by a hill that fills the middle of the small town. Phou Si stands in silent watch over the city it has guarded for centuries.

Luang Prabang, previously called Muang Sua and Xiang Dong Xiang Thong, was the ancient capital of the Kingdom of Lan Xang Hôm Khao (meaning “one million elephants and the white parasol”). The elephants represented military power and the parasol symbolic of Buddhist royalty. Better known as Lan Xang, the kingdom was founded in the mid-14th century by the famous ruler Fa Ngum. The city had existed before the foundation of Lan Xang as a vassal of the Khmer empire. Fa Ngum, with the support of Angkor, carved a kingdom out for himself and his bride, the Khmer princess Kèo Kèngkanya. Originally he settled in Viang Chan Viang Kham (Vientiane) and in order to assert his religious agenda, he enshrined the Prabang (or Pha Bang) Buddha image there. The Prabang was a gift from Fa Ngum’s father in law, the Khmer king. When he later moved his capital to Xiang Dong Xiang Thong, he brought the image, along with Khmer monks and Theravada Buddhism with him. The city was renamed Luang Prabang (Royal Buddha Image in the Dispelling Fear Mudra) in honour of the sacred statue it was now home to.

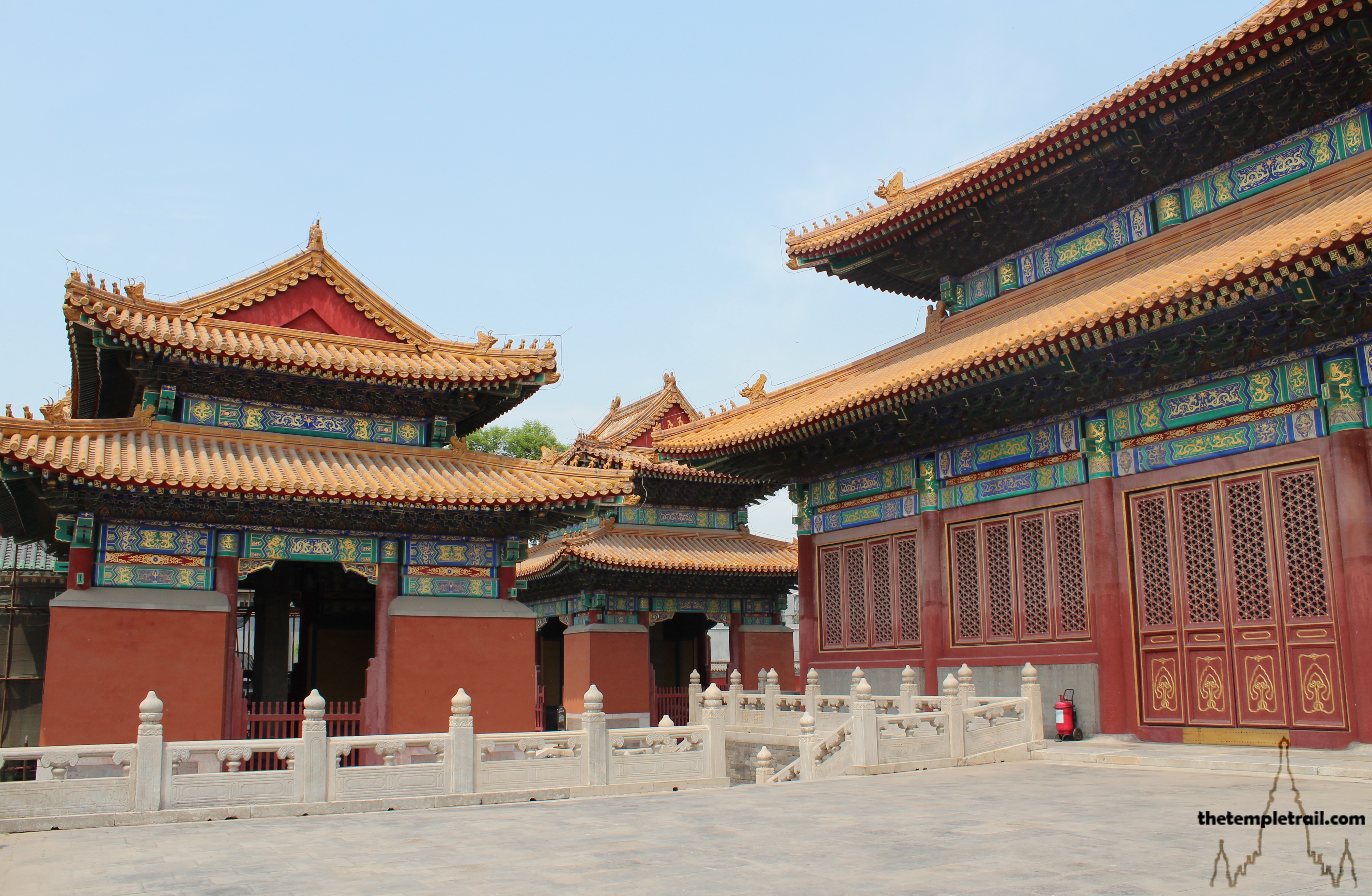

To your right is the legacy of that image. The Royal Palace (now museum) grounds are host to a temple that is almost complete. The construction of the Haw Pha Bang was begun in 1963 during the reign of Sisavang Vatthana, the last King of Luang Prabang. After the Pathet Lao came to power, they forced his abdication and work halted as the communists tried to eradicate religion and disparaged the Prabang as a royalist symbol. The policy changed in the early 1990s, and work on the temple started again in 1993. The Haw Pha Bang will, when fully completed, be the final resting place of the Prabang. The sacred image has lived in Vat Wisunalat and Vat Mai, but now rests in the palace museum. Unable to resist, you are drawn to the shrine on the outside of the palace building to look at the famous Prabang. The image only ever leaves at Lao New Year for ritual cleansing at Vat Mai. The image is almost solid gold and at 83 centimetres, it weighs a hefty 50 kilograms. The diminutive statue is magnetically potent and your eyes are dazzled by its presence. The hands are in the Abhayamudra, or dispelling fear gesture and it is a strangely reassuring presence. Indeed, looking at it, you can see how it rallied a nation around Fa Ngum and subsequent rulers. It has moved between Luang Prabang, Vientiane and Thailand on several occasions, but soon it will have a permanent home in the temple being built for that very purpose.

Constructed in the Luang Prabang style, the sim (ordination hall) is huge. It is made of concrete, steel and other non-traditional materials. It is vastly over the top and the tall platform and ornate roof, combined with its sheer size elevate it to the status required for the home of such a sacred image. Gold covers so much of the interior and exterior while nāgas and dragons rest on every bannister. Inside, the throne of the Prabang sits empty. It will be a proud moment when the image is enshrined in this glorious building. Having had your fill of this new and empty feeling structure, you move on to the large mound that awaits you across the road.

Phou Si (Holy Mountain) is a beautiful hill in the heart of the city. It is covered in vegetation and is the lush green mound that divides the two rivers of the region. Along its northwestern vista is the iconic Mekong River and below it on the other side of the isthmus, the Nam Khan flows. All around the 100-metre-tall hill, low-lying buildings frame the natural protrusion. As you climb up the first steps, you see a small temple on a brief plateau. Near the temple, a Bodhi Tree offers some shade, much as one of its magnificent forbears did to the Buddha as he gained enlightenment. This, as most are, is a cutting from the one at Bodhgaya; the location of the enlightenment. It was donated by the Indian Government in 1957 to mark the 2500th anniversary of the Buddha’s passing to nibbāna (nirvāṇa).

Vat Pa Houak (Monastery of the Thornless Bamboo Forest) is a small temple, of which only the sim still exists. It was founded by the monk Phaya Si Mahanam in 1861 in what was then a bamboo forest. The Vientiane-style sim looks somewhat shabby after years of poor maintenance, but it remains charming. Above the doors, the damaged façade depicts the god Indra riding his elephant Erawan. The rest of the plaster and mosaic has almost entirely fallen from the wooden structure, and indeed the Indra relief is a reconstruction. Entering the doors past the weathered portico and its octagonal columns, you step into a magical little space. The walls are covered from top to bottom in colourful murals. These murals are contemporary with the construction of the building during the reign of King Chantharath in the mid-19th century. Despite being worn by the elements and disparaged by the great chronicler of French Indochina Henri Parmentier, the frescoes glow with energetic vibrancy. The murals depict a rather unusual subject. The main theme is Buddha humbling the boastful King Jambupati, a story and depiction popular in Burma. They also depict Luang Prabang as an international utopia and typical scenes of the time. You feel the warmth of the small chamber emanating from the artwork and the statues of Buddha that hold court here.

Back in the daylight, you find yourself at the foot of a set of steps that appear to climb into the heavens. The trek takes you through tropical undergrowth and the path is lined with the holy champa trees (frangipanis), the national flowering tree of Laos. The sweet intoxicating fragrance embeds itself in your nostrils, making your ascent more paradisiacal. As you break through to the top, a golden spire shimmers through the vegetation. Clearing verdant greenery, you come out onto a rock escarpment and see the stupa in its full glinting glory.

Vat Phra That Chomsi, built in 1804, is seen by the locals as the most sacred spot in the city. The famous golden that (stupa) can be seen from almost any point in the town, like a beacon that illuminates the entire peninsula. Built at the end of the reign of King Anourathurath, the that was restored in 1914 and 1926 upon the construction of the staircase. That Chomsi is a Laotian-style stupa and is tall and angular. It resembles a stylized unopened lotus bud and parallels can be drawn to the large Pha That Luang in Vientiane. The 21-metre-tall that is the point at which a procession begins during the Lao New Year. It sits on a three-tiered base and is protected on the diagonal points by four golden seven-tiered ceremonial umbrellas, like the one that tops the main spire.

From the base of the stupa, you look out at the city that surrounds you. To your left is the Nam Kahn, to your right, the Mekong. The view is the best in town and all around you temple roofs glimmer in the sunlight. Looking back at the that, you recall the legendary story of its foundation. Before the stupa was constructed, a danger-filled tunnel to the centre of the world was found here. A local monk entered the shaft and found a glorious treasure. The greedy locals stole the treasure from him and trapped the monk in the pit. The monk defeated the seven guardians of the treasure and escaped due to his magical powers. When the King heard the story, he punished the locals and the stupa was built.

Leaving the pinnacle, you go past a Russian anti-aircraft gun that is rusted and has not seen use for many years. The urge to get on it and play is primal and giving into your impulse, you spend a minute or to pivoting around on it. The zig-zag stairs bring you to Vat Tham Phou Si (Holy Mountain Cave Temple), also from 1804. It is actually a cave shrine and mostly consists of various statues in different poses. The Monday Buddha stands with his hands in the Pacifying the Relatives mudra like a sentinel, while the Tuesday Buddha reclines in nibbāna. The small cave grotto has an interesting statue of Pha Kasai (Kātyāyana or Kaccāna). Although a little unusual to see in Laos, the fat bellied image (not be confused with the Chinese Bùdài) is more popular in Thailand, where he is called Phra Sangkajai. One of the original Ten Disciples of the Buddha, he studied under the Hindu ascetic Asita who predicted that Gautama Siddhartha would become a great king or a Buddha. Caves have a particular significance in Buddhism, as they are a place to both dwell and meditate for a monk. They are a place for retreat and reflection and the Buddha himself also used caves for this purpose. In the Thai and Laos Forest Tradition, monks wander the forests until the rains retreat, when they enter the monasteries. If a monk is in a cave, he will hang a yellow cloth at the cavern opening.

Passing the statues and following the path further, you see a small shrine on the cliff edge. It is for local spirits, and echoes similar such shrines in the neighbouring Southeast Asian countries. As with its neighbours, Laos still retains an animist sub-religion. The Baci ceremony, for example, is a ritual used to invoke the 32 Kwan (spirits of the body’s organs) and is as deeply ingrained in the Lao religious psyche as Buddhism is. Under the shrine, you come to Vat Phra Bat Nua, marked by a nāga banister. Not much remains of the temple built during the reign of Phaya Samsenthai in the late 14th century. The kingdom of Lanna (now Chiang Mai in Northern Thailand) is said to have heavily influence the temple styling. The main feature is the metre-long Buddha footprint. The footprint is a natural recess in a stone and has been painted gold to highlight it. It is covered by a small shelter. The footprint is symbolic of the transmission of the teachings of Buddha. In early Buddhism, images of The Buddha were unheard of. The earliest temples depicted Buddha’s footprint and natural ones were particularly revered.

Finally, you make your ultimate descent. Here, on the southern flank of the hill, you look out over the Nam Khan. A bamboo bridge spans it so that locals can have access to their land. Vegetables grow in neat little rows on the other side of the bank and from here, the only sign that you are in the 21st century is the two plastic umbrellas of a makeshift beach on the sandy flats of the river. Casually climbing down the hill, you enter back into the sleepy town. If it were not for the few cars, you could be forgiven for feeling like a time-traveller. As the sun begins to go down, you settle into a café behind the hill for a cup of tea and some kaipen, a snack made of dried algae and served with Jeow bong (chili paste). The night falls quickly here and as the light dims, you feel yourself filled with a tranquillity that countless weary travellers have felt before you in the ancient city in the heart of the Laotian jungle.

Imperial Temple of Past Emperors

Imperial Temple of Past Emperors