The dense jungle swaddles your tuk-tuk as it hobbles along time-worn dirt tracks. The beauty of your surroundings is astounding. Every nook and cranny seems to hold hidden secrets. Occasionally a red sign pops into view informing you of the danger of stepping off the path. The whole area was a mine field during the darkest days of the Khmer Rouge and the skull and crossbones on the sign transcends any written language. The jungle is still a dangerous enigma and for the foreseeable future, to wander into the forests off the beaten path unguided is a fool’s errand. The ancient city-state of Angkor is far removed from the traveller town of Siem Reap that acts as its gateway.

You are currently on your way to a hugely important temple from the golden years of the Angkorian Empire. Having just visited its sister temple of Ta Prohm, the fabulous Preah Khan beckons you to pay it a visit. Both temples were built in the late 12th century by Jayavarman VII, the great Buddhist ruler of Angkor. Originally named Nagara Jayasri (city of victorious royal Fortune), Preah Khan was built on the battle site where Jayavarman defeated the invading Cham forces. The modern name, Preah Khan, nods its head to this and means holy sword due to a legend that the sword of the king was kept at the temple. The temple housed an image of Shri Jayavarmesvara (Lokeśvara or Avalokiteśvara, the bodhisattva of compassionate mercy) that was fashioned in the likeness of his father, King Dharanindravarman II. He did this with his mother, Queen Sri Jayarajacudamani, at Ta Phrom also; the statue there of Prajñāpāramitā (the bodhisattva of perfect wisdom) was an image of his mother. Much like Ta Prohm, Preah Khan functioned as a city and as a Buddhist University. 515 other statues were enshrined there and the riches of the temple are clearly stated on the foundation stone. On top of the 97,840 attendants and servants of which, 1000 were teachers and 1000 dancers, the temple owned gold, gems and 112,300 pearls. It also had a cow with gilded horns. The temple was later iconoclastically converted into a Hindu sanctuary by King Jayavarman VIII. The area served as a medical centre and proponents of Khmer, Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine practiced there. As with many Angkorian temples, it was surrounded by a city. The one that encircled Preah Khan covered 56 hectares and was bordered off by a 700 by 800 metre wall.

As you step down from your tuk-tuk’s carriage, you are greeted by hawkers, but they seem less pushy than those at other sites and leave you alone when you show disinterest. Maybe it’s the waning afternoon sun and the way that the light is blocked out by the dense jungle canopy, but you feel as if something magical and spectral awaits you inside.

Contrary to the intended way to visit the site, you start in the west, rather than the east. Your procession towards the western city entrance, brings you face to face with the heads and tail of an enormous nāga on either side of the ceremonial pathway. Lined up holding the naga are the devas (gods) and asuras (anti-gods). The scene on this nāga bridge depicts Samudra manthan (the Churning of the Ocean of Milk), a pivotal story in Hindu mythology. These giants and nāga (like at Angkor Thom), are evidence that this was a royal city. It has been put forward that it was the provincial residence of Jayavarman VII as his city was being repaired after the Cham attack.

Threading through the straining bodies and down the walkway that once went through a bustling town, you look back at the city wall that protected it from attack. The 72 five-metre high Garuda (mythical bird-man) carvings gave the wall more than just physical defensive properties. You come to the central gopura of the temple’s western gateway and its intricately carved fronton (tympanum) that depicts the Battle of Lanka from the Ramayana.

The temple is a maze of collapsed corridors and chambers. Only the central axial passageways are clear. The corbelled roof holds strong and allows you to pass freely and occasionally dart out into the sunlight and spaces that are totally filled with debris. Picking your way through the rubble, apsaras (temple dancers/nymphs) and devatas (demi-gods) peek out from the side of walls at you. Each time you explore a room in the labyrinthine complex, you need to return to the central corridors. This western section of the site was rededicated to Vishnu (Viṣṇu) the sustainer and pilgrims would have prayed to the Hindu god in this section of the temple.

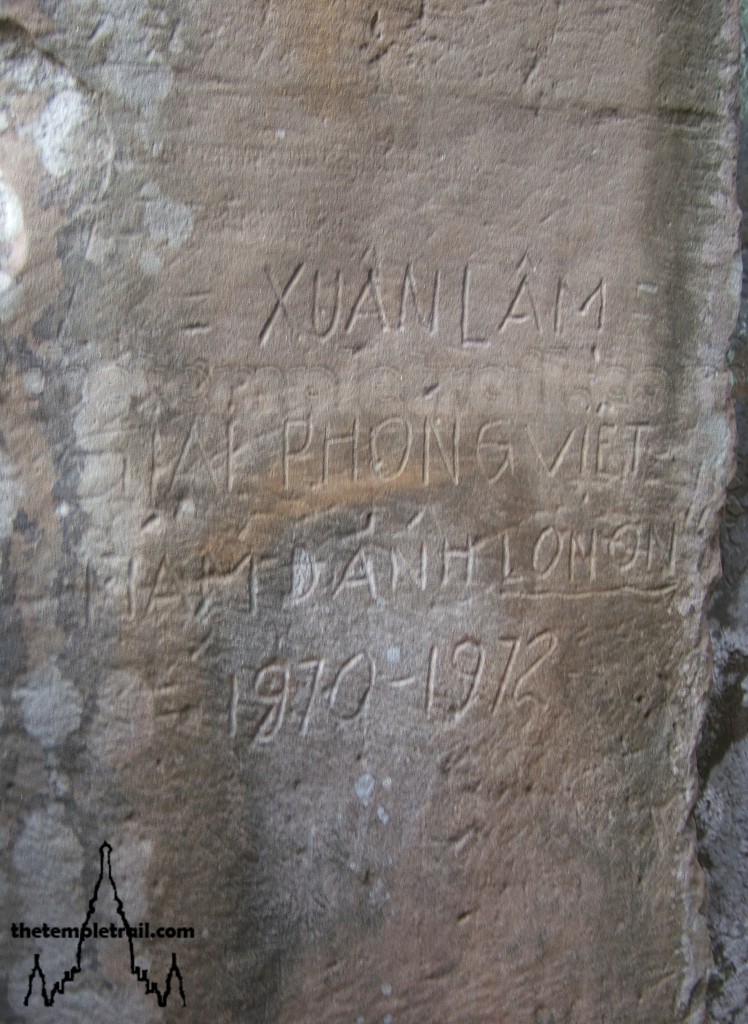

Your eye catches some vandalism. It isn’t ancient, but tells of a significant chapter in the temple’s saga. The writing is in Vietnamese and was carved by soldiers who occupied the temple as a base for several years. This set of writing was from when the soldiers were friendly with the Khmer Rouge. During the Vietnam War, Cambodia was in the throes of its own civil war. The whole area was a battleground and the Northern Vietnamese supported the insurrection at the same time as fighting the Americans. Fast forward a few years and the boot was on the other foot when the Vietnamese returned to Angkor. This time they fought against the Khmer Rouge. The etched wall in front of you is testimony to the living history of the site and lets you know that the temple’s story is far from finished.

Coming to the crux of the two corridors, the pivotal crossroad is home to a 16th century stupa. This place once housed the main bodhisattva image of Shri Jayavarmesvara that was moved to the National Museum. Here, you are directly below the central tower and you are right in the heart of the temple. The galleries and buildings around the central enclosure contain large numbers of devatas and dvarapalas (temple guardians) among the rubble and fallen masonry. The small shrine buildings in this enclosure were added later and the goddess Lakshmi (lakṣmī, the consort of Vishnu) was venerated here along with the god Shiva (Śiva).

Amid the general disorder, you see that the intact wall sections have even holes all over them. These holes once held wooden doweling that supported bronze sheets encasing the central area. Combined with flaming torches it added to the spectacular feel, lighting up the building in a holy and mysterious light. The sections would have been closed with wooden doors and the corbelled roof paneled. It is among the central buildings that two special reliefs are found. Depicting two devatas, Srei Krup Leak as they are called, are venerated by local people who want to conceive. The devatas represent Jarayajadevi and Indradevi, the two wives of King Jayavarman VII. This is continued evidence of the method Jayavarman VII used to show himself and his family as being divine.

From here, you continue eastward to the Hall of the Dancers. The cruciform gallery is famed for its eight lintels lined with dancing apsaras. The lovely carvings are crowned with niches that were erased of their Buddhas by Jayavarman VIII during his conversion of the temple. It is in this chamber that pilgrims would have given their offerings to monks for the bodhisattva Lokeśvara.

Bursting forth from the hall, you are on the eastern walkway of the temple. To your left as you walk towards the eastern city gateway is the dharmasala. The usage of this building is unclear, but the name suggests that it is believed to have been a rest house for pilgrims. It is sometimes referred to as the fire house and some think that it housed a sacred fire. The building is inaccessible, but you enjoy a view of it from the outside. Beyond the eastern gate lie boundary stones (much like the sao nang charang at Phanom Rung in Thailand) that feature images of Buddha. The evidence of the later Hindu reuse of the temple can be seen by the many defacements on these markers.

Walking back down the path to the eastern gopura of the temple, you observe two kapok trees in a death roll with the wall, building and tree dependent on each other for stability. Returning to the centre of the maze, you go a small way south from the stupa until you cannot go any further. The southern temple is in a beautiful state of disarray, but does not offer much of a way in. Shiva would have been worshipped both here in the south and in the northern sector of the temple complex. From here you see the picturesque southern city entrance that sits on a grassy and unrestored patch of ground. Making a 180, you pass the axle and go to the north.

The northern sector of the site holds much interest and has a few buildings of note. Apart from the laterite structures that seem so out of place in their rustic form, a one-of-a-kind building rests in what once would have been a water filled moat. The two-storeyed building (also known as the building on stilts) is almost Greco-Roman in appearance and is from a later period. It emulates a wooden granary and the circular columns are very unusual for a temple building in Angkor. Perhaps it acted as a library due to its raised form. There is no extant stairway, but one made of wood must have been part of its substructure. Locals say that the building held the holy sword that the temple is named after, but this is just local folklore and no evidence supports it. Marveling at the building you slowly retreat back into the shadows of the central vaults.

Stepping out from the labyrinth, you feel like Theseus having defeated the minotaur. You are back in the sun and experiencing a sensation of victory, having negotiated the gauntlet. The feeling that something may collapse on you any minute is unfounded, but understandable and out in the open your sense of achievement is genuine. Returning up the path to your tuk-tuk, you head to the modern town of Siem Reap and back to the 21st century. The weight of history is oppressive in this area and a hot shower and comfortable bed await you to help lighten the load.

Goa Gajah

Goa Gajah